The Battle of Ballinamuck

Humbert resumes Operations in the Field—The British Plan of Campaign—Battle of Colooney—Battle and Surrender at Ballinamuck—Case of Bartholomew Teeling.

FTER organizing a government for Connaught, Humbert once more turned his attention to the military situation, and began laying his plans for a march into the heart of the country. In a letter addressed to the Minister of Marine, three or four days after the battle of Castlebar, he had outlined his programme in the following language: "As soon as the corps of United Irishmen shall be clothed, I shall march against the enemy in the direction of Roscommon (to the southeast), where the partisans of the insurrection are most zealous. As soon as the English army shall have evacuated the province of Connaught, I shall pass the Shannon and shall endeavor to make a junction with the insurgents in the north. When this shall have been effected I shall be in a sufficient force to march to Dublin, and to fight a decisive action."

He explained in this letter that the slow progress of the French was due to the hesitancy of the Irish allies; and in order that "this handful of French" may not be obliged to yield to numbers, he asked that reëforcements be sent, consisting of one battalion of the 3d Half Brigade of Light Infantry, one of the 10th Half Brigade of the line, 150 of the 3d Regiment of Chasseurs a Cheval, and 100 men of the Light Artillery; also 15,000 fire-locks and 1,000,000 cartridges. "I will venture to assert," were his concluding words, "that in the course of a month after the arrival of this reëforcement, which I estimate at 2,000 men, Ireland will be free!"

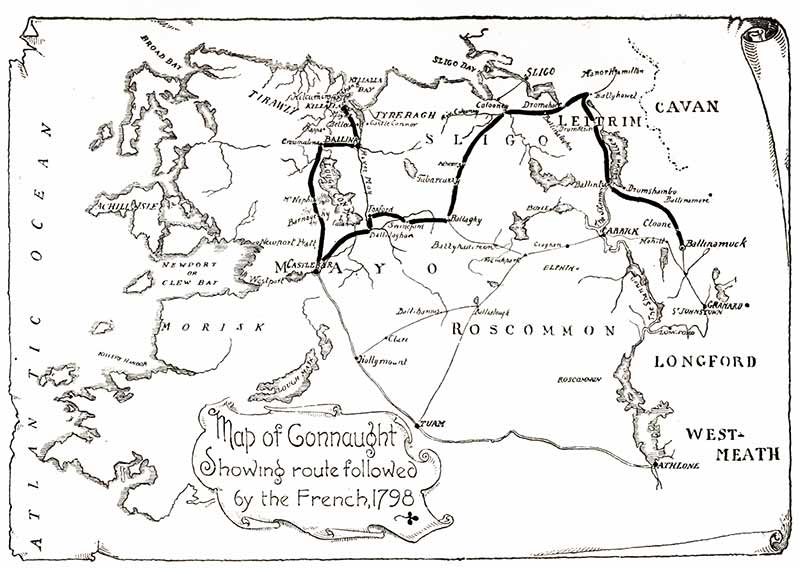

Humbert was apparently ill-informed regarding the situation at the time he penned his appeal to the French Directory. The county of Roscommon was but a very small portion of the disaffected district, which in reality comprised counties Leitrim, Cavan, and Monaghan to the northeast, and Longford and Westmeath (48) to the east (see map). In fact the revolutionary spirit extended even to Dublin. From the day of the French landing, the village blacksmiths everywhere had been busily employed manufacturing pikes, the "croppy's" favorite weapon, and the preparations were now complete for a general uprising and coöperation with the French forces in their march to the capital. It being generally assumed that the invaders would select the shortest route, which was through Longford, it was determined to aid them by the seizure of the town of Granard, a strong post situated on an eminence near the county line. The leaders in this movement were two men of property, Alexander and Hans Denniston, who lived in the neighborhood of Granard, and although members of the Mastrim yeomanry cavalry, had secretly espoused the patriot cause. The advent of the French in Mayo had been anticipated for months by the revolutionists in Belfast and many northern towns, and when the news came of the advance on Ballina, Hans Denniston repaired north to deliberate with the rebel leaders. It was intended that the attack on Granard, then weakly garrisoned, should take place immediately on his return.

In the meanwhile reëforcements to the Longford army came pouring in from all sides, Westmeath sending 3,000 men and Roscommon an almost equally large number. In Monaghan and Cavan, on the other hand, large bodies of men were held in readiness to march at a moment's notice and form a junction with their brethren as soon as Granard should be taken. The Monaghan army alone numbered 23,000 men, according to a reliable authority, and was armed with matchlocks, sabres and pikes, but lacked cannon and ammunition; and in order to make up for this deficiency the leaders proposed to attack the town of Cavan, containing a well-stocked depot of war material.(49)

As far as Humbert was therefore concerned, everything pointed toward a rapid advance in the direction of Granard. But here already the results of his dilatory policy commenced making themselves felt. On the morning of September 3d he was informed of the presence of Lord Cornwallis at Athlone, with a large body of regulars, and of the concentration of other hostile armies further south and east. He considered it inadvisable to encounter such a force with his insignificant body of French and his more numerous but entirely undisciplined Irish contingent; so, having learned from a spy named Jourdan that counties Sligo and Leitrim were comparatively free from the enemy, he decided to adopt that circuitous route to the capital. He sent orders to the troops he had left at Killala, and a small detachment stationed at Ballina, to meet him en route, and on the night of September 3d the first division of his army, with the baggage and cannon, set out for Sligo. The next morning the second division followed, about 400 Frenchmen and from 1,500 to 2,000 Irish auxiliaries. The majority of the "patriots" had preferred remaining behind, presumably to look after the "government."

On leaving Castlebar, the French general gave his eighty prisoners their liberty, as they would only have proved an incumbrance during the march. Doctor Ellison was one of them. When the French were fairly out of sight he sent a letter to Lord Cornwallis, who was supposed to have reached Hollymount, fourteen miles to the south. Emboldened by the continued absence of the invaders—it had been suspected at first that their departure was but a feint—the Doctor by and by started out himself on the Hollymount road, where he met Colonel Crawford with a cavalry detachment, consisting of some Hompeschers—Hessian mercenaries—and Roxburgh Fencibles. Informed of the state of affairs in Castlebar, the colonel proceeded thither at full speed, accompanied by Ellison. They reached their destination at a late hour in a pouring rain, and their appearance created a veritable panic among the insurgents. Crawford immediately sent for John Moore, the previously mentioned "President of Connaught," and ordered him to disclose any information he might possess touching the route and plans of the French army. As the unfortunate man declared himself ignorant on the subject, the colonel ordered a dragoon to draw his sword and decapitate him. This bloodthirsty command so frightened the victim that he fell on his knees, invoked the saints, and begged for mercy, producing at the same time his commission as "President," an act of self-incrimination that can with difficulty be accounted for, unless, as has been stated by one writer, the President of the Province of Connaught was really under the influence of liquor at the time.

Let us now view the position of his Majesty's forces. On September 3d Lord Cornwallis arrived at Tuam from Athlone, with the army he had formed in the east, a portion of which consisted of the shattered remnants of General Lake's beaten forces. As the British commander lacked information regarding the intentions of the French, he resolved to continue his march to Castlebar with one portion of the army, while General Lake with 14,000 men (50) moved direct northward and joined General Taylor, who after the battle of Castlebar had retreated from Foxford and taken his stand at the village of Ballyhadireen. (See map.) Lake's division was made up as follows: the cavalry consisted of the 23d Light Dragoons, the 1st Fencible Light Dragoons, the Roxburgh Fencible Dragoons, and some mounted carabineers, under command of Colonel Sir Thomas Chapman, Lieutenant-Colonel Maxwell, the Earl of Roden and Captain Kerr; the infantry was made up of the Third Battalion of Light Infantry, the Armagh and part of the Kerry Militia, the Reay and Northampton Regiments, and the Prince of Wales' Fencible Regiment of Fusileers, under the orders of Lieutenant-Colonel Innes of the 64th Regiment, Lord Viscount Gosford, the Earl of Glandore, Major Ross, Lieutenant-Colonel Bulkeley and Lieutenant-Colonel McCartney.(51)

This army marched from Tuam on the afternoon of September the 4th, and late the same evening reached Ballinlough, about twenty miles to the north. Another day's march brought it to Ballyhadireen, where Taylor's brigade was encamped. At one o'clock of the 5th, Lieutenant-Colonel Meade was sent out by Lake, with a party of dragoons, to reconnoitre the surroundings and discover whether the rumors of Humbert's departure from Castlebar were true. At a hamlet between Ballyhadireen and Ballahy, an advanced patrol of the reconnoiterers captured a rebel, from whom they learned that the French were on the march northward. This information being communicated to General Lake, Meade was ordered to carry it to Lord Cornwallis at Hollymount. When within fifteen miles of Castlebar, Meade's dragoons fell in with a large detachment of insurgents, posted on a row of hillocks extending down to a bog. The foremost horsemen, without waiting for their superiors' orders, dashed at a party of pikemen stationed at a bridge, and very nearly brought on a general conflict, which would doubtless have proved disastrous to the colonel's mission. Meade, with great presence of mind, spurred to the front and ordered a halt, and perceiving that the rebels were acting in a half-hearted manner, offered them favorable conditions of surrender, which many accepted. The poor wretches had deserted from the French, and were suffering the pangs of hunger and the anguish of apprehension. About sixty muskets were surrendered to the English, after which the prisoners were allowed to depart in peace. Near Swineford, Meade turned to the south, and between Clare and Ballyhanis met the lord-lieutenant, who, having been informed while at Hollymount of the evacuation of Castlebar, was now on his way to the northeast to coöperate with General Lake's division in an advance on the French rear.

Rain fell in torrents when Humbert's army began its march, and the difficulties of the advance were increased tenfold by the muddy condition of the highways. Reports, unfortunately too true, of the hourly growth of the enemy's forces, served to act as a damper on the spirits of the Irish allies, and those who had clamored loudest for the extinction of their Protestant fellow-citizens now dropped out by degrees from the marching ranks, and took themselves off to a place of safety. The desertions, in fact, became so frequent and general, that a guard of French soldiers was finally placed on the flanks and the rear of the Irish column, to check them as far as possible.

The first halt of the army was at a place called Barleyfield, the seat of a wealthy land-owner named McManus. Here the French requisitioned some provisions to be sent on to Swineford, which place the army entered early on the evening of the 4th. Humbert remained unremittingly in the midst of his troops, not even leaving them to partake of his meals under cover of a farm-house. From Swineford the army proceeded to Ballahy, and after another short halt continued on to Tubbercurry. This village was the scene of the first blood shed during the second half of Humbert's campaign. The Corrailiney and Coolavin yeoman cavalry, under Captain O'Hara, advanced to meet the French at the outskirts of the place, and were driven into flight after a short engagement. The British lost one man killed, several wounded, and two prisoners, Captain Russell and Lieutenant Knott. At Tubbercurry the French were joined by a considerable body of rebels who had marched across the mountains from Ballina. They brought with them some Protestant prisoners. These Humbert immediately sent back for the same reasons that had induced him to liberate their brethren at Castlebar.

The march was uninterrupted after this until the army arrived, on the 5th, at Colooney, a romantic village on the banks of the river of the same name, ten miles to the south of the flourishing sea-port of Sligo. The garrison of the latter place numbered six hundred men of all arms, under Colonel Charles Vereker, who, learning from O'Hara of the approach of the French, marched out against them with two hundred and fifty of the Limerick City Militia, twenty of the Essex Fencible Infantry, thirty yeomen, a troop of the 24th Regiment of Light Dragoons and two curricle guns. The inhabitants of Sligo, in the mean time, became a prey to the greatest consternation, expecting to witness scenes of rapine and plunder in their very midst; and their fears were not unjustified either, for the town contained property valued at several hundred thousand pounds, and its harbor was filled with vessels of every size and description. In other words, it offered many temptations to a hostile force.

COLONEL CHARLES VEREKER

According to the colonel's own account, when he arrived within sight of Colooney, at about half-past two on the 5th, he found the French posted on the northern side of the town ready to receive him. His left was sufficiently protected by the river, and in order to secure his right he sent Major Ormsby with one hundred men to occupy a neighboring eminence. The action that followed was obstinately contested. Vereker, with a boldness out of all proportion to his numerical strength, moved forward on the foe along the whole line, and for a while succeeded in maintaining himself. But the French reserves presently came up, and Humbert was enabled to outflank the British right and drive Ormsby and his men into the plain beyond. Fresh bodies of troops were then thrown upon Vereker's right flanks with a view to surrounding him and forcing him to surrender, with the alternative of being driven into the water. The gallant Englishman, who had already received a painful wound, discovered the purpose of his adversary, and having expended nearly all his ammunition ordered a retreat. The British left the field in good order, covered by their cavalry under Captain Whistler, who experienced the satisfaction of repulsing a charge of the French Chasseurs. Notwithstanding the exertions of Captain Slessor, of the Royal Irish Artillery, the two guns had to be abandoned in consequence of the killing of one of the horses. However, as the ammunition wagon and entire gun harness were saved, the cannon proved of little use to the French. The casualties on the British side amounted to one officer killed and five officers and twenty-two rank and file wounded. The French loss was twenty killed and thirty wounded, and the rebels, who fought much better on this occasion than at Castlebar, also suffered to some extent.(52)

Humbert was not backward in paying a just tribute to the pluck and energy of Colonel Vereker.(53) He openly expressed his admiration of the masterly manner in which the British troops had been handled during the engagement, and declared the colonel to be the only man he had encountered in Ireland capable of leading fifty men into battle. The truth of the matter is that the French and British commanders at Colooney each miscalculated the strength of his opponent. Vereker imagined himself to be dealing merely with the advanced guard of the French army, while Humbert was led to believe that he had repulsed the van of a more formidable force. Expecting another attack the French general remained on the field for some hours, forming the rear columns for action as they came up, and then when no enemy appeared he turned to the east, following the high-road to Manor Hamilton, in the county of Leitrim.

Thus Sligo was saved from a hostile occupation, which was all the more unexpected as half an hour after the commencement of the fight at Colooney a number of fugitives entered the town, announcing that the English had been beaten and that the French were advancing. The Protestant population was seized with a panic, and a stampede occurred to the harbor, where thousands of men, women and children boarded the ships in the hopes of at least saving their lives. A few hundreds of the younger men, however, secured matchlocks and pikes, with the determination of defending their homes at any cost, and their efforts were ably seconded by the Protestant clergy. The military who had been left behind by Colonel Vereker, under Colonel Sparrow, occupied the avenues leading to the town, and had the French appeared some desperate street fighting would have resulted. As it was, after an anxious night orderlies arrived from Colonel Vereker with the welcome intelligence that the French had abandoned their designs on Sligo, and the Protestants once more breathed freely.

General Lake, in compliance with the lord-lieutenant's instructions, was meanwhile pressing close on the rear of Humbert's army. From Ballyhadireen he marched on the afternoon of the 5th with his combined forces to Ballahy, through which place he learned the French had passed the preceding evening at about seven o'clock. He marched onward without further delay, and entered Tubbercurry at seven. He found Colonel Crawford awaiting him here with the Hompeschers and the Roxburgh Fencible Cavalry, and henceforth this detachment acted as the advance guard of the army. The services they rendered in harassing the French were invaluable, but their course was marked by the most revolting acts of barbarity. They took no prisoners under any circumstances, but cut down in cold blood all stragglers from Humbert's Irish contingent, and even entire bodies of the rebels who offered to surrender. Thus for miles and miles the road in the wake of the French army was strewn with the dead and dying, farm-houses and private dwellings in the vicinity were reduced to ashes, and devastation was spread all over a lately prosperous country. When the British force reached Colooney, whence Humbert had departed a short while before, a number of wounded French were discovered in a barn under the care of a surgeon. These experienced good treatment; but a Longford deserter who fell into the hands of the Hompeschers received short shrift, and his body, riddled with bullets, was marched over by the entire army.

To accelerate his movements the French general, after leaving Colooney, threw two pieces of cannon into a ditch and five more into the river at Dromahaire, a hamlet on the border of Leitrim. Crawford was close upon his rear, and shots were constantly being exchanged between pursuers and pursued. All this while the ranks of the Irish auxiliaries continued to thin out by desertion, superinduced by fear of summary vengeance; so that forty-eight hours after the evacuation of Castlebar scarcely half of their number remained with the army. The discipline of the French soldiers under all these trying circumstances maintained itself in a most effectual manner. Neither lack of food and rest, nor the fading hope of ultimate success could dampen their ardor. Their march partook of the character of a running fight, devoid of one hour's respite from toil and danger, and at times the enemy's cavalry would approach near enough to occasion a hand-to-hand conflict, in which, while invariably victorious, the French always sacrificed one or more of their meagre force. Within a few miles of Manor Hamilton Humbert learned of the concentration of rebel troops around the town of Granard, and conceiving at last that his only remaining hope lay in attaining this point, whereby he would gain a strategical position of great value between the royal army and Dublin, he wheeled to the right and directed his steps toward the south.

The same scenes that had marked his progress from Colooney attended the latter portion of the march. Crawford still hung obstinately on his rear, and harassed him unceasingly with feints and partial attacks. Between Drumshambo and Ballynamore, however, the English officer overstepped the bounds of caution and made a general attack, which resulted disastrously for him, many of his men being killed or wounded and the remainder put to flight. Humbert was only prevented from surrounding the British on this occasion by the mistaken idea that he was engaged with Lake's entire army. On the afternoon of the 7th the French passed the River Shannon at Ballintra, but so close was the pursuit that they were unable to destroy the bridge, as had been their intention. The powder used by Fontaine, who had charge of the operation, proved insufficient for the purpose, and only a slight break was made, which the British afterward repaired with the ruins of an adjacent house. At nightfall the French arrived at Cloone, and such was the exhausted condition of his men that Humbert found himself forced to give them a couple of hours' rest.

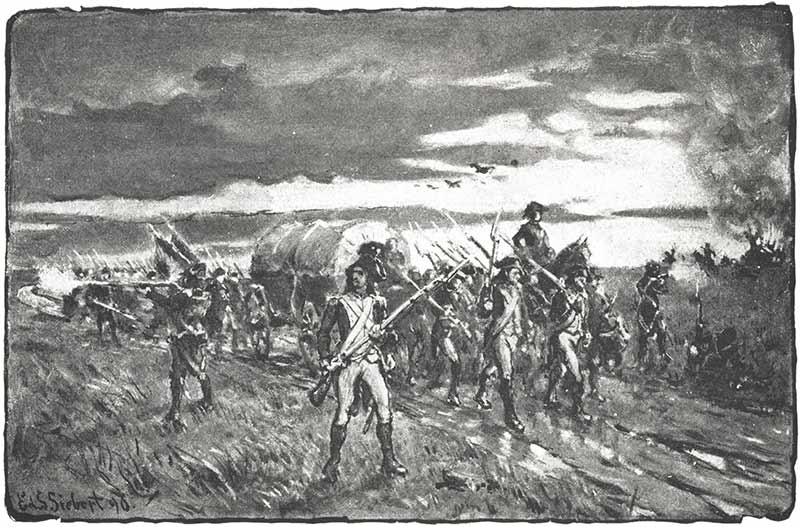

"Their march partook of the character of a running fight, devoid of one hour's respite from toil and danger."—Page 128.

It was at Cloone that he received details of the progress of affairs in Longford and Westmeath. A delegation of insurgents from the neighborhood of Granard informed him that this post had been ineffectually assailed by 6,000 men on the morning of the 5th, and that the following day the patriot armies had experienced a similar check at Wilson's Hospital in Westmeath. Still, they declared that there was no reason to abandon hope, for though unsuccessful in their first efforts, the insurgents were in nowise discomfited, and, fully 10,000 strong, were feverishly awaiting the appearance of their allies, the French. The spokesman of this delegation is described by Fontaine as being armed from head to foot with a large variety of weapons, and bearing in a general way a not remote resemblance to the bold knights-errant of the thirteenth century. He appears to have been a very long-winded and loquacious individual, for the same writer attributes the fatal delay at Cloone solely to these unnecessary pourparlers. From English sources one learns of another cause for this loss of time. It was the first opportunity the French had had of closing their eyes in sleep during four long days and nights. Every minute of that period had been one of anxiety and toil. Humbert appears to have given orders that he and his officers should be awakened at the end of two hours, but the guard let them sleep four, and thus the British army came nearer than he expected. But for the loss of that two hours the French might have succeeded in reaching Granard, and then Cornwallis' plans would have been upset.(54)

General Lake approached Cloone a little before sunrise on September 8th. He had intended to surprise the French during the night, but in the darkness some of the divisions of his army missed their route. The English entered Cloone on one side as the French withdrew on the other.

Lord Cornwallis was on the high-road between Hollymount and Carrick-on-Shannon, on the morning of the 7th, when an officer from Lake's division informed him of Humbert's change of front. The lord-lieutenant immediately guessed his adversary's intention, and while hastening his own march to Carrick, directed Major-General Moore—who had in the mean time been sent to Tubbercurry— to prepare himself for a possible movement against the town of Boyle.(55) Arriving at Carrick in the evening, Lord Cornwallis learned that the French had already passed the Shannon at Ballintra, and were bivouacked at Cloone. Accordingly at ten o'clock the same night he marched with his entire force to Mohill, ten miles further west, where at daybreak on the 8th he was confronted with the fact that Humbert was moving toward Granard. He thereupon sent instructions to Lake to attack the enemy's rear without delay, and himself proceeded with all possible expedition to St. Johnstown, through which place, on account of the breaking down of a bridge, the French would necessarily have to pass in order to reach their destination. (See map.)

In compliance with his instructions, General Lake, after reaching Cloone, redoubled his efforts to force Humbert to an engagement. He mounted five flank companies of militia, viz.: the Dublin, Armagh, Monaghan, Tipperary and Kerry, behind the Hompeschers and Roxburghs, and started them off against the worn-out foe. When the pursuers drew near, the infantry dismounted and kept up an incessant fire, and, aided by the cavalry, obliged the retreating troops to slacken their pace. Seeing that a battle was unavoidable, the French general finally brought his men to a standstill and made the necessary preparations. Defeat stared him in the face, but, as on former occasions, he was resolved to uphold the honor of his country's flag at any sacrifice. With his usual coolness in moments of danger, he addressed a few words of encouragement to the brave men who had stood by him through the long period of trials and perils, and exhorted them to do their duty to the very last. He posted the army on a hill near the hamlet of Ballinamuck, four miles from Cloone, and the same distance from Mohill. His left was partly protected by a bog, and his right by another bog and a lake. The position was altogether as advantageous a one as could have been selected under the circumstances, but the enormous numerical superiority of the English reduced Humbert's chances, even of escape, to absolutely nothing.

At the very commencement of the action a most regrettable incident occurred, for which no satisfactory explanation has ever been given. General Sarrazin, who during the entire campaign had distinguished himself beyond all praise, was suddenly seen to gallop down the first line of the rear division, flourishing his cap on the point of his sword, as a signal of surrender; whereupon the division grounded their arms.(56)

At this moment the Earl of Roden and Colonel Crawford advanced with their cavalry, and perceiving the movement in the French lines ordered the trumpet to sound. It was answered on the French side, and two British officers riding forward alone, a parley ensued. The Englishmen demanded the immediate surrender of the French army. Sarrazin replied that the matter must be referred to the commander-in-chief, then stationed some distance behind on the Ballinamuck road with the main body.

While this conversation was in progress, General Taylor mistakenly informed General Lake that the French army had capitulated, and the British commander then despatched the "lieutenant-general of ordnance," Captain Packenham, and Major-General Craddock to receive Humbert's sword. The officers rode over to Humbert's line, but, to their consternation, were received with a volley which wounded Craddock in the shoulder.(57) Then it became clear that some misunderstanding had occurred. It appears that Humbert, upon learning of his subordinate's parley with the enemy, burst into a fit of indignation, and, repudiating any idea of surrender, ordered the advance at double-quick. Lord Roden had by this time induced Sarrazin to capitulate, and Crawford, confident of meeting no further opposition, had advanced on the French lines with a body of dragoons. In a moment all was changed. Humbert's Grenadiers rushed at the dragoons and made them prisoners, together with their two leaders, while the rest of the horse, savagely attacked on two sides, scampered away with precipitation.

Now the action became general. Lake, attempting to imitate Humbert's tactics at Colooney, threw a column of troops on the right of the French, with a view to outflanking them. Perceiving this Humbert withdrew his main body from the hill to another eminence further back. The British artillery was then moved to the front; but when Lake saw a large body of stalwart pikemen form into a solid column for the purpose of charging the guns, he ordered the latter withdrawn and continued the battle with infantry and cavalry. On the brow of a hill, a quarter of a mile from the spot where Sarrazin had surrendered, a number of French tirailleurs were posted with some artillery, and these did much execution in the ranks of the British right. The English general himself at one moment came within range of their fire, and narrowly escaped with his life. After a good deal of firing on both sides, he at last ordered his light infantry and cavalry to ascend the hill from two points, which they did with enthusiasm; but not until every tirailleur had either been killed, wounded or made prisoner, was the French cannon finally silenced and the battle won.

During the whole conflict Humbert maintained his reputation as a skilful leader and a brave man. Unwilling to survive defeat, he threw himself in the midst of the enemy, sword in hand, and but for the intervention of his aide-de-camp, Teeling, he would probably have been killed by the dragoons, who bore him down from his saddle. Lord Roden and Colonel Crawford remained prisoners in the midst of a body of chasseurs until the Roxburgh Fencibles came up in search of their colonel. The French officers, realizing then that further resistance would only lead to the useless sacrifice of many valuable lives, surrendered their swords and ordered the firing to cease.

As far as the French were concerned the battle was ended. But now the most horrible act in the drama was to be played. The unfortunate rebels, who still numbered several hundreds, expecting no quarter, fought on with the frenzy of despair. Driven from the guns which they had helped to serve, not without loss to the foe, they fled into a bog and were here surrounded by horse, foot and artillery. Lake's hour of revenge had sounded, and he made full use of his opportunity. Raked with a galling cross-fire from all points, sabred by the horsemen and bayoneted by the infantry, there soon remained but a skeleton of the solid column that had stood side by side with Humbert's troops at the beginning of the battle; and those who finally were allowed to lay down their arms only exchanged the bullet or sword for the rope. Here is what one eye-witness has written:

"We pursued the rebels through the bog—the country was covered for miles around with their slain. We remained for a few days burying the dead—hung General Blake and nine of the Longford militia; we brought one hundred and thirteen prisoners to Carrick-on-Shannon, nineteen of whom we executed in one day, and left the remainder for others to follow our example!"

"They are hanging rebels here by twenties together," wrote an officer of the Reay Fencibles to his friends. "It is a melancholy sight, but necessary."

And here are another eye-witness' words: "There lay dead about five hundred; I went next day with many others to see them; how awful! to see that heathy mountain covered with dead bodies, resembling at a distance flocks of sheep—for numbers were naked and swelled with the weather. We found fifteen of the Longford militia among the slain."

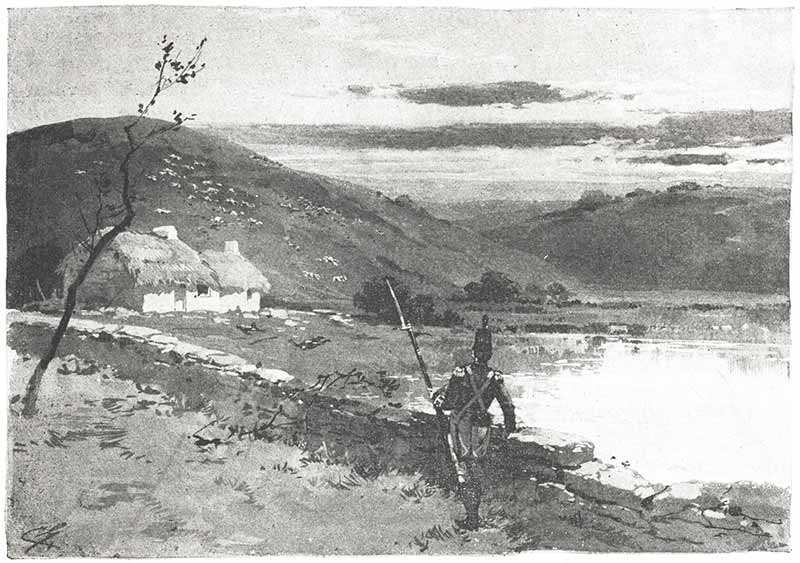

"How awful to see that heathy mountain covered with dead bodies, resembling at a distance flocks of sheep."—Page 136.

General Richard Blake, referred to above, was a gentleman of Galway who had joined the patriot cause shortly before the battle of Castlebar, and had commanded a division of Irish auxiliaries during the later operations. His request to die by the bullet instead of the rope was denied. He bore his fate with the dignity of a hero, as did likewise one O'Dowd, another rebel of prominence. As the executions were proceeding on the battle-field, one of the doomed Longford militiamen demanded the reason for his condemnation. He was told that death was the punishment for desertion provided by the military code. "Desertion indeed!" was the reply. "It seems to me the men who ran away from Castlebar were the real deserters, and not I. They took to their heels without attempting to fight, and left me behind to be murdered by the French." The force of the argument impressed itself on Lord Jocelin, who was standing by, and he interceded with success for the man's life.(58)

Humbert was conducted before the English general immediately after his surrender. "Where is your army?" asked Lake, surprised at the small number of his opponents. "There it is yonder," coolly replied Humbert, pointing to a group of fagged-out men and horses in the background; "there you have my entire force." "And what did you propose doing?" asked Lake. Humbert seized the opportunity to indulge in one of his favorite fanfaronades: "I proposed marching on to Dublin," he answered, drawing himself up in a theatrical attitude, "there to rend asunder the chains of those who are suffering beneath your tyrannical yoke!" Lake shrugged his shoulders, with the remark: "Such a project could only find birth in a Frenchman's brain." He thereupon ordered the French general to be taken to the lord-lieutenant, at St. Johnstown.(59)

The return of prisoners showed the French army to have been reduced to 96 officers and 746 men, with 100 horses and three field guns; and of these survivors many were sick and wounded, or disabled by incessant marching. The brave men had marched almost a hundred English miles since the day of their departure from Castlebar. Their actual loss at Ballinamuck has never been definitely ascertained; that of the British has officially been placed at three men killed, twelve wounded, and three missing, although there are reasons for believing that the figures were considerably higher.

The treatment of the French prisoners reflects credit on the British military authorities. They received many attentions and courtesies on all sides, and at Longford the officers were entertained at a sumptuous banquet. Expressing his surprise at the rejoicings and illuminations in the streets over the "victory," Adjutant-General Fontaine obtained the explanation, sotto voce, from an English officer, that his countrymen were really "illuminating their own stupidity and the triumphs of the French." The prisoners were sent to Dublin by the Grand Canal, and, as steam was unknown in those days, their journey lasted nearly a week. They travelled on six large barges, the first one carrying the escort of Fermanagh militia with a full military band, the second one the captive officers, and the remainder the rank and file. Nothing, according to contemporary accounts, could exceed the nonchalance and merriment with which the French bore their situation. They seemed to consider that, having fully performed their duty as patriots and soldiers, they had every reason to congratulate themselves on the conclusion of a most trying and ungrateful task; so they were constantly collecting in parties, conversing with the utmost gayety, playing cards, dancing, and above all, singing the Marseillaise.

In Dublin—although, for prudential reasons, the prisoners were not allowed to show themselves in public—they were frequently complimented for their conduct during the campaign, and at their arrival in Liverpool an immense crowd gathered to greet them with many manifestations of friendliness. At Litchfield, where the officers were temporarily quartered, General Humbert was actually visited by a deputation of clergymen, headed by no less a person than the Lord Bishop, a brother of Cornwallis, who expressed their gratitude for the protection extended by him to the Protestants of Connaught.

Humbert's first request to the British authorities was that his Irish officers receive considerate treatment. He could offer no reason for leniency on behalf of those who had taken up arms against the Crown after the arrival of the invaders, but he insisted all the more on immunity for such as had come over from France and held commissions in the French army. Particularly solicitous was he about Teeling, his aide-de-camp. On this subject Teeling's brother has written feelingly, as follows: "After the surrender of the French army a cartel was concluded for the exchange of prisoners, under which General Humbert, with the residue of his forces, was to proceed to France. The most bitter regret was evinced by the French general in finding that Teeling was not to derive the benefit of this arrangement. The latter, as already observed, had surrendered prisoner of war when his general was captured. His person was easily identified; recent circumstances had made him known to General Lake; but (and I mention this circumstance with a feeling of gratitude and admiration), though between him and several of the British officers on the field an early and familiar intercourse had subsisted, they had the generosity, under his present circumstances, not to make any recognition. On taking muster of the French officers he was set apart and claimed as a British subject by General Lake. Humbert remonstrated; he demanded his officer in the name of the French Government; he protested against what he conceived a breach of national honor and of the law of arms. 'I will not part with him,' he exclaimed with violent emotion. 'An hour ago, and ere this had occurred he should have perished in the midst of us with a rampart of French bayonets around him! I will accompany him to prison or to death.' And this generous soldier did accompany his aide-de-camp to Longford prison, where he remained till the following day, when the French prisoners were conveyed to the capital, and thence embarked with the least possible delay on board transports for England. Teeling was removed to Dublin to be tried by court-martial. Matthew Tone, who had been arrested the day after the battle, was also recognized as an Irishman and retained for trial."

Teeling was brought to trial for high treason less than two weeks after his capture, and, notwithstanding the many proofs adduced of his kindness to loyal prisoners and his strict observance of the rules of civilized warfare, he was condemned to death as a traitor to his country. Humbert, on board the Van Tromp, wrote a touching letter of appeal to the president of the court-martial two days before the commencement of the trial, from which the following is extracted:

"Teeling, by his bravery and generous conduct, has prevented in all the towns through which we have passed the insurgents from proceeding to the most criminal excesses. Write to Killala, to Ballina, to Castlebar; there does not live an inhabitant who will not render him the greatest justice. This officer is commissioned by my government; and all these considerations, joined to his gallant conduct toward your people, ought to impress much in his favor. I flatter myself that the proceedings in your court will be favorable to him, and that you will treat him with the greatest indulgence."

Lord Cornwallis turned a deaf ear to all appeals for clemency on the unfortunate man's behalf, and on the morning of September 24th he was led out from the Prevost to the gallows erected on Arbor Hill. He was attired in the full regimentals of a French staff-officer, and had attended to the details of his toilet with a minuteness bordering on foppery. He wore a large French cocked hat, with a gold loop and button and the tricolor cockade, a blue surtout-coat and blue pantaloons and half-boots. Around his neck was a white cravat, encircled by a black stock, very full and projecting, which the executioner presently removed in order to adjust the noose. The forty minutes that elapsed between the doomed man's arrival under the fatal beam and the completion of the hangman's task he passed in conversation with Brigade-Major Sandes, and until the very last no tremor was perceptible in his voice. Matthew Tone suffered death in a similar manner some days afterward.

The fate of these two men aroused a storm of indignation throughout France, where they were justly considered the victims of a breach of international right. Thomas Paine, the great freethinker, sent an appropriate protest to the Directory, recalling the case of General Lee, of the American army, whom the English were only deterred from hanging as a traitor by a threat of immediate retaliation.(60) The writer urged that the English officers captured at Ostend in the preceding month of May be held as hostages for the French officers of whatever descent that had fallen into the hands of the enemy. He referred more particularly to the prisoners captured on October 12th of the same year, when a French fleet, destined to renew Humbert's attempt on Ireland, succumbed to a superior naval force off Lough Swilly. The Directory, however, in view of the disproportion between the numbers of prisoners in the hands of France and England—the balance being much in favor of the latter—felt themselves powerless to act, and thus Theobald Wolfe Tone, who accompanied the fourth expedition, fell a victim to the same relentless power that had destroyed his brother.