A Second Battle of Castlebar

A Second Battle of Castlebar—Defeat of the Insurgents—The Three French Officers left at Killala—Their Efforts to suppress Religious Persecution—Riot and Lawlessness the Order of the Day—Advance of the Royal Armies—Battle of Killala.

HILE effectually disposing of Humbert's "Army of Ireland," the surrender of Ballinamuck did not end the era of bloodshed in the unfortunate province of Connaught. Undismayed by the reverses of their would-be deliverers, the rebels scattered along the line of the River Moy from Killala to Foxford maintained their defiant attitude. More than that, barely three days after the surrender, 2,000 of them left Ballina under the leadership of Major O'Keon and Patrick Barrett, a former member of the local militia, for the purpose of retaking the town of Castlebar, which, as stated, had fallen into the hands of the British after Humbert's withdrawal.

In the early dawn of September 12th two citizens of the town, Edward Mayley and John Dudgeon, while stationed as pickets in the northern suburb, heard the thud of horses' hoofs approaching from the direction of the gap of Barnageehy, and presently descried two horsemen riding at a furious pace. The pickets sprang into the middle of the road and challenged the strangers with a "Who goes there?" "A friend," said the foremost rider, drawing in his rein. "A friend to whom?" "To the French," was the reply. "Oh, very well," returned the pickets; "where are you going?" The strangers happened to be reconnoiterers of the advancing rebel army, and, ignorant peasants that they were, felt so jubilant at the distinction conferred upon them by their leaders that they gave free rein to their tongues. "We are going to take Castlebar," they explained; "we are captains, and there are 2,000 men following within half a mile of us." Scarcely had the words passed their lips when the pickets seized the bridles and, levelling their weapons at the riders' heads, ordered them to deliver up their arms under pain of instant death. The two rebels, who had evidently mistaken their adversaries for friends, surrendered on the spot and allowed themselves to be taken as prisoners into the town, where their captors raised an immediate alarm. This action doubtless saved Castlebar from recapture and probable pillage, for its defenders consisted only of a small body of Fraser Fencibles, thirty-four armed townsmen, and a corps of yeomanry cavalry; an insufficient force at any time, but especially so when laboring under the disadvantages of a surprise.

Here again it were better to insert the words of one of the badly frightened citizens, some of whose reminiscences have already been quoted in a preceding chapter: "They (the pickets) entered the town shouting 'Murder! murder! Arise to arms, or you will be burned in your beds!' This echoed so loud, all the town rung with it; hundreds repeated it. Men, undressed, rushed into the streets; incessant rain heavily descended; the drums beat 'to arms! to arms!' whilst the dark, solitary walls reechoed 'to arms! to arms!!!' At last the tempest silenced the drum; but no cause could allay the vigilance of our townsmen and the gallant handful of Frasers. The guards continued to bring in prisoners till morning. At last welcome day shone upon our afflicted town. To me it afforded much consolation, my wife being in the pangs of child-bearing all night; though, I thought, will light save us? No; only serve to display our danger. Thus hope and apprehension bent alternately the balance. At length all our forebodings are confirmed by a discovery of the plodding assassins, planted to great advantage around the northwest part of our devoted town."(61)

It was fortunate for the Protestant population that their fate lay in the hands of so able and energetic an officer as the commandant, Captain Urquhart. At the very first note of alarm he assembled his men in the market-place, and assigned them to the most advantageous posts of defence. The main body occupied the market cross, commanding the principal avenues, with the only piece of cannon in town; another division was posted between the market-house and one of the city gates; and a third, composed partly of cavalry, he stationed at the north end, where the rebels were expected to make their main attack. With a view to insuring the safety of his small army in case of a retreat, the captain placed a guard of infantry in a western street near the bridge, and a few cavalrymen at the south entrance, on an eminence opposite the church.

In this order the little army anxiously awaited the expected attack, the issue of which, considering the enormous numerical superiority of the foe, seemed scarcely doubtful. By seven o'clock the rebels had concentrated their forces near the north entrance and opened a heavy fire of musketry on the devoted town. It was answered with much spirit by the Highlanders. The latter, being under cover, experienced little or no loss, while their opponents were picked off by the dozen. Seeing this, Major O'Keon formed a column of assault and made a dash forward, with the object of gaining possession of the first line of defence. Smarting under their losses, the rebels rushed furiously to the attack. Some were armed with matchlocks, some with pikes, and the remainder with a variety of weapons improvised for the occasion. They were received with equal bravery by the Highlanders and townsmen, who for the time being remained steadfastly within their defences, firing with method and precision. At last, at a critical moment, Mr. John Galagher, of the volunteer corps, seized by a sudden impulse, broke from the ranks and attacked the rebels at close quarters. His brother, the captain of the corps, did likewise, and their example was immediately followed by the rest of the defenders in that section. So impetuous was the charge that the rebel column scattered before it like chaff and fled from the field in dire panic, carrying with it O'Keon's reserves. With the exception of a small detachment under Lieutenant Denham, which remained behind to guard the town, Urquhart now led his full force in pursuit of the fugitives. Scores of these were cut down by the cavalry or compelled to surrender, and some who attempted to escape by way of the Castlebar River and lake were engulfed in their waters.

The complete defeat of O'Keon's army must be regarded as a blessing, even by those who have the Irish cause most at heart. So inflamed were the rebels by the exhortations of their fanatic spiritual guides and their desire to avenge the massacres in Wexford and Kildare, that the capture of Castlebar would inevitably have been accompanied by the wholesale butchery of the loyalist inhabitants, and that in spite of the restraining influence of O'Keon and Barrett, both men of judgment and humanity. In fact, one prisoner, with his neck torn by a ball and two bullets in his body, confessed, between his dying gasps, that it had been the intention of many of his associates to plunder the town and destroy every man, woman and child in it, including even the loyal Catholics! The feeling of relief that pervaded all when they beheld the distant hills swarming with the flying foe may therefore well be conceived.

Before describing the closing act of the drama, namely, the recapture of the last strongholds of the rebellion along the River Moy, it will be necessary to dwell at some length upon the condition of that section from the moment that Humbert's march to the north left it virtually in rebel hands. Thanks to Bishop Stock's admirable work, so often referred to in these pages, authentic material is plentiful on the subject. When the two hundred French infantry withdrew from Killala, in the beginning of September, to reenforce the main army at Castlebar, there remained in that town but two officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Charost and Captain Ponson; and they were joined later by Captain Boudet, whom the advance of a loyal detachment had forced from his station at Westport. To the united efforts of these three heroes may be attributed the salvation of the Protestant population from what, at moments, appeared to be inevitable destruction.

Charost himself was a man of charming and sympathetic personality. To many he will appear an even more interesting figure than Humbert. A Parisian by birth, he settled in San Domingo early in life, and subsequently married well; but the war between France and England brought desolation to him, as it had done to many others. He lost all his property, and even his wife and only child, who were captured while on their passage to France, and taken to Jamaica. Unable to obtain any tidings of them the poor man from sheer desperation enlisted in the French service, and worked his way up to a lieutenant-colonelcy. Generous, humane, and mild in manner, but notwithstanding this firm and courageous in an emergency, he soon earned the respect of Protestants and Catholics alike. In religious convictions he was practically a freethinker. He told the bishop that "his father being a Catholic and his mother a Protestant, they had left him the liberty of choosing for himself, and he had never yet found time to make the inquiry, which, however, he was sensible he ought to make, and would make at some time, when Heaven should grant him repose. In the interim he believed in God, was inclined to think there must be a future state, and was very sure that while he lived in this world it was his duty to do all the good to his fellow-creatures that he could." The well-intentioned prelate appears to have attempted Charost's conversion, but with indifferent success. He gives him credit, however, for respecting the beliefs of others, and taking scrupulous care, among other things, that the divine services of the Protestants at the castle at Killala should not be disturbed in any manner whatever.

Ponson and Boudet, though each interesting in his own way, lacked some of the sterling qualities of their superior. The former was a curious little body, not exceeding five feet six inches in height, of most buoyant temperament. He was a Navarrese by birth, "and," says the bishop, "his merry countenance recalled to mind the features of Henry of Navarre, though without the air of benevolence through them; for this monkey seemed to have no great feeling for anybody but himself. He was hardy, and patient to admiration of labor and want of rest. A continued watching of five days and nights together, when the rebels were growing desperate for prey and mischief, did not appear to sink his spirits in the smallest degree. He was ready at the smallest notice to sally out on the marauders, whom, if he caught them in the act, he belabored without mercy and without a symptom of fear for his own safety. He was strictly honest, and could not bear the want of this quality in others; so that his patience was pretty well tried by his Irish allies, for whom he could not find names sufficiently expressive of contempt."

In startling contrast to Ponson, Boudet, the later acquisition to the French "garrison," is described as being a man six feet two inches in height. "In person, complexion and gravity," says the bishop, "he was no inadequate representation of the Knight of La Mancha, whose example he followed in a recital of his own prowess and wonderful exploits, delivered in measured language and an imposing seriousness of aspect. His manner, however, though distant was polite, and he seemed possessed of more than common share of feeling, if a judgment might be formed from the energy with which he declaimed on the miseries of wars and revolutions. His integrity and courage appeared unquestionable. On the whole, when we became familiarized to his failings, we saw reason every day to respect his virtues."

Regarding Truc, the French officer left at Ballina, the bishop's verdict is not so favorable. He denounces him as a man of evil disposition, lacking both in common honesty and courage. Truc shared his authority with O'Keon, and both stood under the orders of Charost.

The first problem that presented itself to the commandant after the departure of his men for the front related to the means of maintaining the security of the large district intrusted to him, embracing as it did many square miles of rugged country, an extensive seaboard, and the towns of Killala and Ballina. This whole section was swarming with the armed bands of insurgents who had remained behind for the purpose of plundering the Protestant landholders in preference to joining the French in the field. They numbered several thousands, and might have constituted a sufficiently marked accession of strength to have changed the course of events. In consequence of their turbulence and lawlessness a strong guard at first nightly patrolled the town of Killala and its suburbs; but as this measure did not suffice to preserve the peace, Charost decided to offer the proper means of self-defence to every well-disposed citizen. By a special proclamation the inhabitants of both persuasions were invited to come to the castle and receive arms and ammunition, with no other condition than the promise of restoring them on demand. The offer was eagerly accepted by Protestants and Catholics alike, but the result was a failure after all. From the very first the insurgents protested against the arming of their loyalist fellow-townsmen, their argument being that the weapons would surely be turned against themselves. The protestations soon turned into menaces, which so intimidated some of the Protestants that they returned the arms on the very night they had received them. The insurgents, not satisfied with this, adopted, on the few following days, the tactics of harassing the loyalist minority with domiciliary visits, ostensibly for the purpose of searching for concealed weapons, so that from sheer desperation the unfortunates finally petitioned the commandant to call in by proclamation all the arms he had given out, excepting those in use by the recruits for the French service. With a lively appreciation of the situation Charost granted their request, and applied himself to devise another means for ending the depredations that were terrorizing the community.

In imitation of the methods employed by Humbert in the town of Castlebar, he issued a proclamation some days later, establishing a provisional government over the district within his care. He divided it into departments, each presided over by a magistrate, attended by an armed guard of sixteen or twenty men. None of these were required to declare themselves either for or against the king, being simply considered civil officers engaged in the service of keeping the peace. Mr. James Devitt, a substantial Roman Catholic tradesman of good sense and moderation, was unanimously elected civil magistrate for Killala, and thenceforth the town was regularly policed by three bodies of fifty men each, all standing directly under his orders.

However, as time wore on the task of restraining the evil passions of the ignorant multitude became truly herculean. Covetous eyes were cast at the bishop's residence, where, in addition to his family, the three French officers were housed. Few dwellings offered more temptations than his, for besides his own property it contained many valuables deposited in his keeping by the Protestant inhabitants during the first fright occasioned by the landing of the French. For the defence of the castle a guard about twenty strong was drawn from the garrison. The men were relieved once in twenty-four hours, but even they constituted a poor guarantee for the security of the household, imbued as they were with the idea that all Protestant possessions were rightfully theirs. At times the situation was most alarming, and only the tact and nerve of the commandant averted the threatened explosion.

On one occasion a drunken fellow named Toby Flannigan, who had promoted himself to the rank of major, arrested a Mr. Goodwin, a Protestant, for no other reason than that he was a Protestant. Word of the affair was brought to Charost while engaged in a game of piquet at the castle, and immediately the whole party repaired to the scene of the trouble. They found the "major" mounted on his charger, drunk and vociferous, surrounded by an admiring mob. Charost's order to release the prisoner was met by an impudent refusal. It was a critical moment. Failure to enforce his authority would have released anarchy and all its attendant horrors. Charost immediately ordered Flannigan to dismount. There was a ring of determination in his voice that brooked no delay. The culprit looked at his adherents for support, and finding none sullenly obeyed. Charost with his own hands divested him of his sword and pistols, and sent him under a guard of his own followers to the very jail that had opened its doors to the Protestant victim. This incident terminated Mr. Toby Flannigan's martial career.

Although the nominal head of almost all Mayo, Charost's personal influence extended, unfortunately, little beyond the immediate vicinity of Killala. At Ballina, thanks to the supineness or connivance of Truc, the insurgents were able to carry things with a high hand. Father Owen Cowley, of Castleconnor, was their leader. Being a master of the French tongue he had ingratiated himself in Truc's favor, and soon wielded almost unlimited authority over the town and its environs. His ulterior object seems to have been the extirpation of the heretics, and in pursuance thereof he steadily and deliberately labored to instil the poison of hatred and distrust into the Frenchman's mind. On the pretence of securing the young republic against the machinations of inside enemies, Cowley sent out bands of armed insurgents to arrest and bring to town the Protestant farmers of the neighborhood; and in a few days over sixty of these poor people, after seeing their houses demolished, were committed to a temporary jail in the house of Colonel Henry King. Having made sure of his prey, Cowley's next step was to gain permission to destroy them, but here he found an unexpected obstacle in the opposition of O'Keon and Barrett.

Suspecting the priest's designs Barrett interrogated him, and was haughtily told that Truc had given orders for the execution of the prisoners. Barrett flew to the chief, and through an interpreter laid the matter before him. It then transpired that Cowley had lied—a fact that Barrett took good care to charge him with in the most public manner. The young man's temerity, however, nearly cost him his life, for while he was still speaking one of the priest's followers made a lunge at him with a pike, and only his precipitate retreat saved him from the fury of the bloodthirsty mob.(62)

Cowley's methods and intentions savored strongly of the good old inquisition days. On the night of September 8th, about twelve o'clock, this disciple of Torquemada entered the improvised jail to gloat over his victims. They were packed together like sheep, in a room scarcely large enough to hold half their number. Surmising that in the confusion attending their arrest some Catholics might have been included, he greeted them with the words: "Lie down, Orange; rise up, Croppy." Robert Atkinson, of Ballybeg, one of the prisoners, noticed the speaker's clerical garb and approached him with a request for protection, but for answer received a stunning blow over the head with a heavy bludgeon. Cowley worked himself into a passion, and shaking his fist at the unfortunates, exclaimed: "You parcel of heretics have no more religion than a parcel of pigs. I do not know whether you will be put to death before ten o'clock to-morrow by being burned with barrels of tar, or by pikes, or by balls!"(63) He supplemented this agreeable programme by adding his doubts whether balls "would find room in their bodies." The priest's sanguinary intentions were happily not carried into effect, for when Charost's attention was called to the danger of the Protestants he came in person to Ballina, and reprimanded Truc severely for listening to any accusations on the score of religion. He ordered all persons arrested by Cowley's henchmen to be brought before him, spent a full day in their examination, and discharged every one of them. The poor wretches were free to return to their homes. To many that word meant but a heap of ashes.

A volume, indeed, would not contain the list of outrages committed in the name of Romanism and—strange concomitant—Liberty! The malice of the insurgents was early directed against a Presbyterian meeting-house between Killala and Ballina. It had been built for the worship of a small colony of weavers brought from the north by the Earl of Arran. Their pastor, the Reverend Mr. Marshall, had devoted himself to fitting it up in a style worthy of its character, and so universally was he respected that all the Protestant gentry of the neighborhood had contributed to its embellishment.

The building was utterly demolished in the beginning of September, and the congregation suffered much at the hands of the insurgents. Castlereagh, the seat of Arthur Knox, and Castle Lacken, the property of Sir John Palmer, were also pillaged by an organized band of marauders, and but for his indomitable pluck Mr. Bourke, of Summerhill, would have suffered in a like manner.

News of these various outrages having been brought to Killala, Charost despatched Boudet and Edwin Stock, one of the bishop's sons, to Summerhill to appease the mob, and another party of men to Castlereagh to save what remained of the provisions and liquors. The appearance of the emissaries ended the siege at Mr. Bourke's house; but the Castlereagh party, which consisted entirely of natives, could think of no better expedient for preserving the spirits from the thirsty bandits that coveted them than by concealing as much as they could in their own stomachs. The consequence was that they returned to Killala uproariously drunk. As for Castle Lacken, it was completely gutted, and the occupant and his large family were driven out to seek shelter as best they could find it. Charost's indignation at such barbarity knew no bounds. He told the insurgents that he was a Chef de Brigade, not a Chef de Brigands, and declared that if he ever caught them preparing to despoil and murder Protestants, he would side with the latter to the very last extremity.

In the meanwhile the suspense at Killala, with reference to the progress of the military operations in the east, had waxed acute. Contradictory rumors of an alarmist nature were constantly filling the air, and it was not until September 12th, the day of O'Keon's ill-fated attack on Castlebar, that some definite information reached the authorities at the castle. On the evening of that day William Charles Fortescue, nephew of Lord Clermont, was sent in a prisoner from Ballina, and from him Charost learned of the capitulation of Humbert's force at Ballinamuck. The commandant now felt that a crisis was approaching, for, aware of the temper of the insurgents, he had reason to fear that in the fury of their wrath and despair they would attempt the massacre of every Protestant in town. Conceiving his task of annoying the enemies of his country to be concluded for the present, he looked to nothing further than the preserving of peace and quiet round about him until the arrival of a regular British force should allow him and his companions to surrender without discredit. In pursuance of this determination, and with the distinct purpose to shed his own blood, if necessary, in the defence of the threatened loyalists, he took immediate steps to meet the requirements of the situation. In the apartments occupied by the three officers twelve loaded carbines were kept in readiness, and among the seven or eight trusted members of the bishop's household a variety of weapons were distributed.

THE BATTLE OF KILLALA

Henceforth the Frenchmen remained constantly on the alert, watching not only all newcomers and applicants at the castle gate, but also their own guard of twenty men.

The precautions were by no means superfluous. Day by day the prospect grew more threatening. On September 18th intelligence of General Trench's preparations to march an army against them from Castlebar caused the insurgent leaders to send in a demand to Charost that the Protestants be imprisoned in the cathedral as hostages. This he flatly refused to do. The next day an angry crowd gathered about the castle gate, complaining that their friends and relations in Castlebar were being ill-treated by the British. To quiet them the bishop suggested that two emissaries be despatched to General Trench for the purpose of entreating him to do nothing to his prisoners of a nature to provoke reprisals on the Protestants at Killala. The proposition met with immediate approval. Roger Maguire, son of a Crossmalina brewer, and Dean Thompson, who with his family had occupied the bishop's apartments since the appearance of the French, were selected for the mission, and early on the following morning they started out on their perilous journey.

Their departure did not effect the desired truce. A false report that the English were approaching served to recall to town, on the 20th, a number of pikemen whom the commandant had induced, the evening before, to return to their homes. Rioting and drunkenness became the order of the day. For the fourth or fifth time the house of Mr. Rutledge, the customs officer, was attacked by a band of ruffians in search of plunder. To restore quiet Ponson was called from his couch, where he was sleeping off the fatigues of the previous night. Single-handed he rushed upon the crowd and felled the foremost man to the ground with a blow from a musket. The fury of his charge put the entire band to flight. On the 21st another disorderly mob appeared at the castle gates and clamored for permission to arrest Mr. Bourke, of Summerhill, whose defiant attitude had aroused their ire. They declared that he was abusing his Catholic neighbors. Charost told them curtly to go to Summerhill if they pleased, but added that he would follow them up and fire upon them if he caught them in the act of plundering the house. Later in the day the commandant, by his presence of mind, averted another danger. Just as he was sitting down to dinner word was brought to him that a party of turbulent pikemen had assembled outside the castle, bent on plunder. Charost walked out leisurely, accompanied by his two officers, and "found them preparing to batter in the gates. In his ordinary tone of command he called "attention," divided them into platoons, and proceeded to put them through their daily exercise. His nonchalance completely nonplussed them, and, occupied with their drill, they were effectually diverted from mischief.

Much to the relief of the castle's inmates, the two emissaries returned the same evening from Castlebar. They brought a letter to the bishop from General Trench, giving full assurances regarding the treatment of the rebel prisoners. This was read to the insurgents, and appeared to reassure them. More consoling to the bishop was the information, privately imparted by Dean Thompson, that owing to the situation in Killala the general had decided to commence his march two days earlier than he had intended, and would probably reach them on Sunday morning, the 23d.

The preparations on the part of the British to suppress the insurrection in northwest Connaught had been considerably delayed by the ominous symptoms in the centre of the island. There, as has been shown in the foregoing chapter, an insurrectionary movement of great magnitude had been set on foot in the beginning of September, the intention of the rebels being to coöperate with Humbert's army on its march to Dublin. The surrender of Ballinamuck upset their plans, and none of the projected raids took place; but Lord Cornwallis deemed it imprudent to detach any troops from the main army until he had fully assured himself that all danger from a renewed outbreak was over. And thus it came to pass that fully ten days elapsed between the battle of Ballinamuck and General Trench's appearance in Castlebar with a force destined to restore the king's authority over the entire province.

Trench was determined that no loophole of escape should be left to the rebel forces. His plan was to attack them from different sides, leaving them no alternative but to surrender or be driven into the sea. Lord Portarlington, who was stationed at Sligo with the Queen's County Regiment, a small body of the 24th Light Dragoons, and several corps of yeomanry, was ordered to march to Ballina and form a junction there with the main body from Castlebar; and at the same time a force of 300 of the Armagh militia at Foxford, under Major Acheson, and another 300 men at Newport, under Colonel Fraser, were to converge to the same point from their respective stations.(64) Lord Portarlington's troops, being the farthest off from the common destination, were the first to move. Almost 1,000 strong, with two pieces of field artillery, they started from Sligo on the morning of September 21 st. They were not molested until nightfall, when a body of rebels approached them at their halting-place, near the village of Grange. One cannon-shot sufficed to disperse the assailants. The British did not get off so easily on the following night. They had scarcely entered the village of Scarmore when they were attacked by a column of pikemen, who had advanced from Ballina under the command of O'Keon and Barrett. A prolonged and obstinate encounter followed, in which the insurgents were at length worsted. Before the commencement of the action, a number of Protestant farmers living in the neighboring hamlet of Carrowcarden had been impressed into service by the pikemen, and in order to insure their coöperation they were placed in the first line of battle. The natural consequence of this proceeding was their absolute annihilation by the royal troops.

The three remaining British divisions began their march on Saturday, September 22d. Major Acheson was vigorously assailed by a rebel command, but succeeded in beating them off. General Trench, whose army was composed of the Roxburgh light dragoons, the Devonshire, the Kerry and the Prince of Wales' Fencible Regiments, the Tyrawley cavalry and two curricle guns, took the road that had been made memorable by Humbert's advance to Castlebar. His progress was slow, for the rain, falling unceasingly, had converted the highways into beds of slime. The division entered Crossmalina Saturday night, worn out with the wearisome march. News of their approach reached Killala in the afternoon, and the pikemen at once demanded to be led against the foe; for with all their bigotry and ruffianism these uncouth peasants were never lacking in animal courage. Ferdy O'Donnell, of Erris, one of their leaders, placed himself at their head, and the march began. At Rappa the commander was taken sick and the little army halted; but a reconnoitring party of three mounted men, including Roger Maguire, already mentioned, pushed forward as far as the outskirts of Crossmalina. They there fell in with a picket of sixteen cavalry, whom they boldly attacked and put to flight, actually following the fugitives into the town itself. The weakness of the reconnoitring party was concealed by the darkness, and their appearance caused a veritable alarm—the drums beating to arms and the soldiers rushing wildly through the streets. Having attained the object of the reconnoissance the riders departed at full gallop to rejoin their comrades, whom they dissuaded from continuing the march, on the ground that too little ammunition was on hand for a general engagement.

The march of General Trench's division was resumed at daybreak on the 23d, and in a couple of hours it entered Ballina to find the town already occupied by Lord Portarlington. Truc and O'Keon had fled at the latter's approach, with the remnant of their followers. No time was now lost in pushing the operations to a final issue. In order to cut off all the avenues from Killala Trench divided his forces, and while advancing with one division by the common highway, he sent the Kerry regiment of militia and some cavalry, under the orders of Lieutenant-Colonel Crosby and Maurice Fitzgerald (commonly known as the Knight of Kerry), to the same destination by a detour through the village of Rappa. It is a circumstance worthy of comment that, in spite of the difference in their routes, the two divisions reached Killala at about the same time.

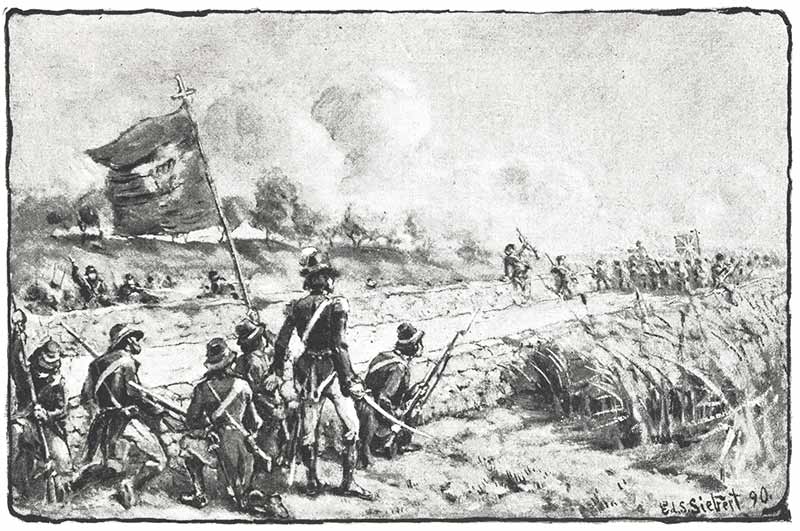

Bishop Stock thus describes the engagement that followed: "The peaceful inhabitants of Killala were now to be spectators of a scene they had never expected to behold—a battle; a sight which no person that has seen it once and possesses the feelings of a human creature would choose to witness a second time. A troop of fugitives from Ballina, women and children tumbling over one another to get into the castle, or into any house in the town where they might hope for a momentary shelter, continued, for a painful length of time, to give notice of the approach of an army. The rebels quitted their camp to occupy the rising ground close by the town; on the road to Ballina, posting themselves under the low stone walls on each side in such a manner as enabled them, with great advantage, to take aim at the king's troops. The two divisions of the royal army were supposed to make up about 1,200 men, and they had five pieces of cannon. The number of the rebels could not be ascertained. Many ran away before the engagement, while a very considerable number flocked into the town in the very heat of it, passing under the castle windows, in view of the French officers on horseback, and running upon death with as little appearance of reflection or concern as if they were hastening to a show. About 400 of these misguided men fell in the battle and immediately after it; whence it may be conjectured that their entire number scarcely exceeded 800 or 900.

"We kept our eyes on the rebels. They levelled their pieces, fired very deliberately from each side on the advancing enemy: yet (strange to tell) were able only to kill one man, a corporal, and wound one common soldier. Their shot, in general, went over the heads of their opponents. A regiment of Highlanders (Fraser's Fencibles) filed off to the right and left to flank the fusileers behind the hedges and walls; they had marshy ground on the left to surmount before they could come upon their object, which occasioned some delay, but at length they reached them and made sad havoc among them. Then followed the Queen's County militia and the Devonshire, which last regiment had a great share in the honor of the day. After a resistance of about twenty minutes, the rebels began to fly in all directions, and were pursued by the Roxburgh Cavalry into the town in full cry. This was not agreeable to military practice, according to which it is usual to commit the assault of a town to the infantry; but here the general wisely reversed the mode, in order to prevent the rebels, by a rapid pursuit, from taking shelter in the houses of townsfolk, a circumstance which was likely to provoke indiscriminate slaughter and pillage. It happened that the measure was attended with the desired success. A great number were cut down in the streets, and of the remainder but a few were able to escape into the houses, being either pushed through the town till they fell in with the Kerry militia from Crossmalina, or obliged to take to the shore, where it winds round a promontory forming one of the horns of the Bay of Killala. And here, too, the fugitives were swept away by scores, a cannon being placed on the opposite side of the bay which did great execution.

"In spite of the exertions of the general and his officers, the town exhibited almost all the marks of a place taken by storm. Some houses were perforated like a riddle; most of them had their doors and windows destroyed, the trembling inhabitants scarcely escaping with life by lying prostrate on the floor. Nor was it till the close of the next day that our ears were relieved from the horrid sound of muskets discharged every minute at flying and powerless rebels. The plague of war so often visits the world that we are apt to listen to any description of it with the indifference of satiety; it is actual inspection only that shows the monster in its proper deformity.

"What heart can forget the impression it has received from the glance of a fellow-creature pleading for his life, with a crowd of bayonets at his breast? The eye of Demosthenes never emitted so penetrat-ing a beam in his most enraptured flight of oratory. Such a man was dragged before the bishop on the day after the battle, while the hand of slaughter was still in pursuit of the unresisting peasants through the town. In the agonies of terror the prisoner thought to save his life by crying out 'that he was known to the bishop.' Alas! the bishop knew him not; neither did he look like a good man. But the arms and the whole body of the person to whom he flew for protection were over him immediately. Memory suggested rapidly:

"'What a piece of workmanship is man! the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals! And are you going to deface this admirable work?'—Hamlet.

"As indeed they did. For, though the soldiers promised to let the unfortunate man remain in custody till he should have a trial, yet, when they found he was not known, they pulled him out of the court-yard as soon as the bishop's back was turned, and shot him at the gate."

This engagement, so graphically described, nearly proved disastrous to the brave men whose advocacy of the great principle of religious liberty had already exposed them to so many perils. In the indiscriminate slaughter which followed the battle, the royal troops, elate with victory and inflamed by revenge, showed small respect for persons. Charost's escape from death was almost miraculous. After having done his share in the defence of the rebel position, he had returned to the castle and surrendered his sword to a British officer. As he turned to enter the hall he was shot at by a Highlander who had forced his way past the sentinel at the gate. The ball fortunately passed under Charost's arm and pierced the heavy oaken door. The English officer here interposed and tendered an apology for the soldier's act. It is needless to say that every courtesy was shown to the French prisoners after this, exception being made of O'Keon only, who, in spite of his rank in the French army and his claim to French citizenship, was some days later sent a prisoner to Castlebar to be tried for high treason. In response to Bishop Stock's appeal in his behalf, he was acquitted of the charge, but enjoined to leave the country on the shortest notice.

Two days after the battle the three French officers were ordered to Dublin, and one can readily believe the bishop's assertion that he parted with them "not without tears." The story of their honorable and courageous attitude during the long period of disorders having preceded them to the capital, they were received there with many marks of consideration, and they enjoyed the hospitality of no less a person than the lord primate himself. On the report of Bishop Stock the British Government offered to return them to the French authorities without exchange, but this act of courtesy was not accepted by Niou, the French commissary. These men, he declared, had merely followed their line of duty. They had done no more than what was expected of any French officer in a like situation. They were therefore not entitled to special favors.

The fate of the insurgents who escaped sword and bayonet was a far different one. A court-martial to try them began its sessions on Monday morning, the 24th of September, and early on Tuesday the first two victims were handed over to the executioner. These were an irresponsible drunkard named Bellew and one Richard Bourke, of Bellina. The authority of the Crown continued to be asserted in a ruthless manner for many weeks afterward, and even six months later fresh victims were found to swell the lengthy list. There has been no hesitation in pointing out in these pages the many acts of insurgent ruffianism prompted by religious intolerance and race and political hatred; but it is only justice to add that ruffianism and rapacity constitute the worst charges that can be preferred against the unfortunate peasants engaged, after all, in a struggle with a galling despotism. In the words of Bishop Stock, "during the whole time of civil commotion not a drop of blood was shed by the Connaught rebels, except in the field of war." This circumstance should in all justice have carried some weight with the conquerors and have dictated a policy of mildness and conciliation, instead of one of blood and fire. Yet what could be expected of men who in the name of the king and the constitution had already, months before, turned the most flourishing parts of the land into a wilderness?

* * * * *

And thus ended General Humbert's glorious but abortive expedition, as insufficiently supported by the French Government as by the United Irishmen. Any further examination into the various causes that contributed to the maintenance of British misrule in the afflicted country would be superfluous here. The foregoing narration of fact speaks for itself, and fully answers the question. The careful reader can only deduce the inference that the principal cause lay in the Irish people themselves. The fate of the expedition became a foregone conclusion from the moment the rebels showed their colors. Their inability to separate the political from the religious idea made them the subservient tools of men whose one aim was to supplant the reigning despotism with a theocracy no less tyrannical. Had they been imbued with the same broad and liberal spirit which animated the thirteen colonies of America, their energies would not have been wasted in the waging of a petty religious persecution, but would have been expended in the field against the common enemy. What might not a force of 10,000 determined patriots, in conjunction with Humbert's army, have accomplished in the early part of the campaign? Probably an annihilation of Lake's forces. And had the rebels done their duty even after the French general's ill-advised sojourn at Castlebar, is it not fair to assume that the result of the battle of Ballinamuck would have been different? Even though it may be maintained that Humbert's loss of time at the village of Cloone practically sealed the fate of the French army, and that at its best his chance of ultimate success was problematical in the extreme, it is certain that the onus of his failure rests primarily on the insurgents' shoulders. Their cause was a noble one, but they failed to grasp its true significance. May the lesson not be lost on a future race of patriots!