St. Fiacc’s Nemthur was situated in the suburbs of Boulogne

I.

Natus est Patritius Nemturri

Ut refertur in narrationibus,

Juvenis (fuit) sex annorem decem

Quando ductus est sub vinculis.

II.

Succat ejus nomen in Tribubus dictum,

Quis ejus Pater sit notum,

Filius (fuit) Calpurnii, filii Otidi,

Nepos deaconi Odissi.

III.

Fuit sex annis in servitate,

Excis hominum (Gentilium) non vescebat,

Fuit ei nomen adoptivum Cothriagh

Quatuor Tribubus quia inserviit.

IV.

Dixit Victor(ei) servo

Milchonis, Iret trans fluctus.

Posuit suos pedes supra saxum,

Manet exinde ejus vestigia.

V.

Profectus est trans Alpes omnes,

Trans Maria, fuit faelix expeditio

Et remansit apud Germanum

In australi parte australis Lethaniae.

The following beautiful free translation of these verses is taken, with kind permission, from Monsignor Edward Watson, M.A.’s, translation of St. Fiacc’s ode:

I.

“At Nemthur, as our minstrels own,

Heaven’s radiance first on Patrick smiled,

But fifteen summers scarce had thrown

A halo round the holy child,

When captured by an Irish band

He took their Isle for fatherland.

Succat by Christian birth his name,

Heir to a noble father’s fame.

Calphurnius’ son, of Potit’s race,

And deacon Odis’ kin and grace,

Six years of bondage he must bear

With faithful fast from heathen fare.

And Cothriagh now his name and due,

Who holding high allegiance true,

Yet served four little lords of earth

(God’s servant he of forefold worth)

Till Victor bade him Milchu’s slave

To fly across the freeman’s wave.

He fled, but first upon the rocky shore

His footprint set a seal for evermore.

II.

Then far away beyond the seas,

In happy flight o’er many a land,

O’er many a mountain on he flees

To face Lethania’s southern strand,

Nor rested long upon the road

Until he gained Germain’s abode.”

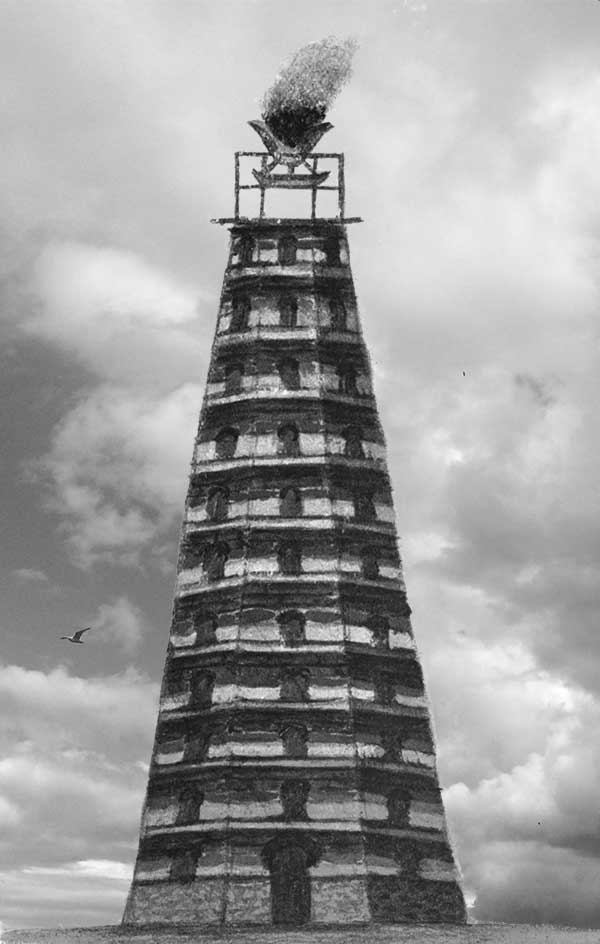

Caligula’s Tower, called Nemtor by the Marini.

St. Fiacc states that the Apostle of Ireland was born at Nemthur—Nemthur, as all commentators agree, is not the name of a town, but of a tower. “Neam-thur Hebernica vox est quæ cœlestem, sive altam turrim denotat.” “Neamthur is an Irish word which denotes a heavenly, or a high tower” (Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Tom i., p. 96—O’Conor).

Assuming that St. Patrick was born in the suburbs, and close to the town of Bononia, or Banaven, as it has already been proved from his “Confession,” St. Fiacc’s declaration that his Patron was born at Nemthur admits of a very lucid explanation.

Nemthur was situated in the suburbs and close to the town of Bonaven. St. Fiacc gives the name of the district, but St. Patrick gives the name of the town near which he was born.

Singularly enough Caligula’s famous tower on the sea coast of Boulogne was called Turris Ordinis by the Romans, but Nemtor by the Gauls, as Hersart de la Villemarque clearly proves in his “Celtic Legend” (p. 213), and the tower itself has given its name to the locality where it once stood, which is called even at the present time Tour d’Ordre—the French translation of “Turris Ordinis.”

The history of this tower, on account of its close connection with the history of St. Patrick, cannot fail to be interesting.

Caligula, or Caius Cæsar, who died a.d. 41, meditated a descent upon Britain, and with that object marshalled his troops at Bononia. Fearful, however, of the dangers and fatigues of a long campaign in that inhospitable island, and full of childish vanity, he determined at length, as Suetonius humorously observes, “to make war in earnest; he drew up his army on the shore of the ocean, with his ballistæ and other engines of war, and, while no one could imagine what he intended to do, on a sudden commanded them to gather up sea shells and fill their helmets and the folds of their dresses with them, calling them ‘the spoils of the ocean due to the Capitol and the Palatium.’ As a monument of his success, he raised a lofty tower, upon which, as at Pharos, he ordered lights to be burnt in the night time for the guidance of ships at sea” (“Lives of the Twelve Cæsars,” Caligula, p. 283).

“It seems generally agreed,” writes Forester, the translator of Suetonius’ Lives, “that the point of the coast which was signalised by this ridiculous bravado of Caligula, somewhat redeemed by the erection of a high house, was Itium, afterwards called Gessoriacum and Bononia (Boulogne), a town belonging to the Gaulish tribe of the Morini” (note, p. 283).

For many centuries this tower called Turris Ordens, Turris Ardens, or Turris Ordinis by the Romans, and Neamthur by the Gauls, spread its light over land and sea on the north-eastern cliffs of Boulogne.

A description of the tower is given in the “Memoirs of the Academy of Inscription,” quoted by Bertrand in his “History of Boulogne,” as follows:

“The form of this monument, one of the most striking erected by the Romans, was octagon. It was entirely abolished about a hundred years ago, but, fortunately, a drawing of it, made when the lighthouse was still perfect, is still in existence, and has been exhibited to the Academy by the learned Father Lequien, a Dominican monk, native of Boulogne. Each of its sides, according to Bucherius, measured 24 to 25 feet, so that its circumference was about 200, and its diameter 66 feet. It contained twelve entablatures, or species of galleries, on the outside, including that on the ground floor. Each gallery projected a foot and a half further than the one above it, and consequently their size diminished with each succeeding gallery. On the top fires were lighted to serve as a beacon to vessels at sea. A solid foundation was formed, not only under the lighthouse, but for some distance beyond the external walls. It was constructed of stones and bricks in the following manner: first were seen three layers of stones, found on the coast, of iron grey colour, then two layers of yellow stone of a softer nature, and upon these two rows of hard red bricks, two inches thick, and a foot and a half long, and a little more than a foot broad” (“Bertrand’s History of Boulogne,” pp. 13, 14).

“Caligula’s tower was built on the north-eastern cliffs, about half a mile from the sea, but within the suburbs of Boulogne. The constant encroachment of the tide had reduced that distance to 400 feet in 1544, when Boulogne was captured, and fortifications built around the tower by the English troops. Still, however, the merciless waves rushed onward to the coast, undermining the cliffs more and more, until at length, on July 29th, 1644, Caligula’s tower fell headlong with a crash into the sea.

“Passengers from Folkestone to Boulogne gaze with reverence or curiosity on the Calvary on the north-eastern cliffs, which fishermen salute with uncovered heads when sailing out to reap the harvest of the sea. Close to the Calvary there is a mass of ruins overhanging the cliff, which is all that remains of the fortifications built round Caligula’s tower by the English conquerors. The tower itself once stood over the site occupied by the Hotel du Pavillion et des Bains de Mer, opposite the place for sea bathing” (“Bertrand’s History of Boulogne,” pp. 15, 16).

“The Celtic Legend,” published by Hersart de la Villemarque in 1864, clearly shows how the history of Bononia and of its celebrated tower is connected with his—St. Patrick’s—life. One of the legends is entitled “St. Patrick,” and commences as follows: “On the shore of the channel separating England from France, near the famous place from which Cæsar embarked for the Isles of Britain, a fortified enclosure was erected overlooking and protecting the coast and territory which formed part of the possession of the Morini Gauls. This important strategic point was called in Latin, Tabernia, or the ‘Field of Tents’ (Le Champs du Pavilion), because the Roman army had pitched their tents there. About a mile distant, a group of buildings formed a fairly-sized village, which at first was called by the Gauls Gessoriac, then Bonauen Armorik, and afterwards named Bononia Oceasensis by the Roman Gauls, and finally Boulogne-sur-Mer by the French.

“A light-house, or Nemtor, as it was called in the Celtic language, kept watch during the night over the camp, village, and sea, preserving the Gaulish frontier from piratical incursions.

“At the foot of the light-house stood the residence of a Roman officer named Calphurnius, who had the supervision of the fire in the tower, amongst the more costly and ornamented houses than the others, where the free-and-easy life and customs of the Romans found a last refuge. He lived there attended by domestic and military servants. He had fought under the Imperial flag and attained the rank of a Decurion (p. 354). …

“Forgetfulness of God, disobedience to His laws, which are also the best laws of human society, led to the ruin both of the colony of Bononia and of St. Patrick’s family. One day a mutiny, from which the servants of Calphurnius could not have kept aloof, broke out amongst the soldiers in the camp, just at the time when pirates, who had come from different parts of the Irish coast and formed themselves into a fleet so as to plunder the towns on the sea coast of Gaul with greater security, took advantage of the dissensions amongst the inhabitants of Boulogne and besieged the town. Fine furniture, carpets, and valuable garments, vessels of gold and silver, arms and instruments of every kind, everything that they could seize in the houses, in the town, in the camp, in the rural dwellings close by, in the stables, in the ox stalls, in the sheep pens: horses, cows, pigs, cattle and sheep were carried off and placed on board the ships. Those who attempted any resistance were put to death, whilst others, undergoing the fate of domestic animals, were sold into slavery. Amongst the defenders of the colony who perished were Calphurnius, his wife, and many of his household. St. Patrick was numbered amongst the captives. The corsairs, having set sail, landed him in Ireland, where they sold him to a small chieftain in Ulster named Milcho” (“La Legende Celtique,” par le Vicomte Hersart de la Villemarque, Membre de l’Institut Paris, 1864, Librarie Academique. Dedier et Cie., Librarie Editeurs, 35 Quai des Augustines).

There is a constant tradition that St. Patrick was a native of Boulogne, and that tradition is expressed in the Celtic Legend just quoted.

Even the present “Guide Book” of that town (Merridew’s, 1905) volunteers the following information, which, although erroneous as to dates, is interesting as referring to St. Patrick’s connection with the city:

“About the year 249 St. Patrick arrived in Morinia, and for some time resided at Boulogne” (p. 10).

Father Malbrancq, in his “History of the Morini,” quotes the “Chronicon Morinense,” “The Life of St. Arnulphus,” and “The Catalogue of the Bishops of that See” to prove St. Patrick’s connection with the town.

Although it is certain that St. Patrick never presided over that See, the fact of his being numbered amongst the Bishops admits of an easy explanation if he was a native of that town.

Boulogne-sur-Mer: St. Patrick's Native Town - Paperback Edition

Boulogne-sur-Mer: St. Patrick's Native Town - Kindle Edition