Britain in Gaul St. Patrick’s native country

Unless it can be proved that there was a province called Britain in Gaul, and another Britain quite distinct from the Island of Britain, it would be useless to argue that St. Patrick was a native of Gaul.

The Saint represents himself as a native of Britain; and even Probus, who is credited with believing that St. Patrick was a native of Armoric Gaul, distinctly states that the Saint was born in Britain (natus in Britanniis).

It is, however, not difficult to prove that there was a province in Gaul called Britain (Britannia) even before the birth of St. Patrick.

Strabo, in his “Description of Europe,” narrates in the Fourth Book that about 220 years before Christ, Publius Cornelius Scipio, the father of Scipio Africanus, consulted the Roman deputies at Marseilles about the cities of Gaul named Britannia, Narbonne, and Corbillo.

Sanson identifies Britannia with the present town of Abbeville on the Somme.

Dionysius, the author of “Perigesis,” who wrote in the early part of the first century, mentions the Britanni as settled on the south of the Rhine, near the coast of Flanders.

Pliny, in his “Natural History,” when recounting the various tribes on the coast of Gaul, mentions the Morini and Oramfaci as inhabiting the district of Boulogne, and places the Britanni between the last-named tribe and Amiens. (Pliny, lib. i., cap. xxxi.; Carte’s “General History of England,” vol i., p. 5).

“The Britanni on the Continent extended themselves farther along the coast than when first known to the Romans, and the branch of that tribe mentioned by Dionysius as settled on the coast of Flanders, and the Britons of Picardy mentioned by Pliny, were of the same nation and contiguous to each other. Dionysius further adds that they spread themselves farther south, even to the mouth of the Loire, and to the extremity of Armorica, which several writers say was called Britain long before it came into general use” (Carte, p.6).

Sulpicius Severus, in his “Sacred Histories,” gives an account of the Bishops summoned by the Emperor Constantius in the year 359 to the Council of Ariminium in Italy. Four hundred Bishops from Italy, Africa, Spain, and Gaul answered the summons, and the Emperor gave an order that all the Bishops were to be boarded and lodged, whilst the Council lasted, at the expense of the treasury. Whereupon Sulpicius, writing with pride of the action taken by the Bishops of the three provinces, Gallia, Aquitania, and Britannia, makes use of the following words:

“Sed id nostris, id est. Aquitanis, Gallis, et Britannis, idecens visum; repudiatis fiscalibus propries sumptibus vivere maluerunt. Tres autem ex Britannia inopia proprii, publico usi sunt, cum oblatum a ceteris collationem respuissent; sanctius putantes, fescum gravare, quam singulos” (Lib. ii., p. 401).

“The proposal seemed shameful to us, Aquitanians, Gauls, and Britons, who, rejecting the offer of help from the treasury, preferred to live at our own expense. Three, however, of the Bishops from Britannia, possessing no means of their own, refused to accept the maintenance offered by their brethren, deeming it a holier thing to burden the treasury than to accept aid from individuals” (Lib. ii., p. 401).

If any doubt exists as to the Britannia referred to, it is solved in the same book, p. 431.

Sulpicius Severus, an Aquitanian by birth, speaks of the trial, condemnation and punishment of the Priscillian heretics by the secular Court at Treves in the year 389.

Prisciallanus and his followers, Felicissimus, Armenianus, and a woman named Euchrosia were condemned to death and beheaded, but Instantias and Liberianus were banished to the Island of Sylena, “quae ultra Britanniam sita est” (which is situated beyond Britain).

Although it is not precisely known where the Island of Sylena was situated, except that it was somewhere beyond Britain, the Britain referred to surely must be Britain in Gaul, for it is incredible that the Gauls should possess a penal settlement in the North of Scotland, where Sylena must have been situated, if the words “beyond Britain” refer to the Island of Britain.

It is evident that if Sulpicius, who was born in 360—thirteen years before St. Patrick—could speak of Armorica as Britannia, and the Armorican Bishops as Britons, when he wrote his “Sacred Histories,” it cannot be a matter of surprise that St. Patrick, if born in Armorica at a later period, should speak of himself as a Briton, and say that he had relatives among the Britons.

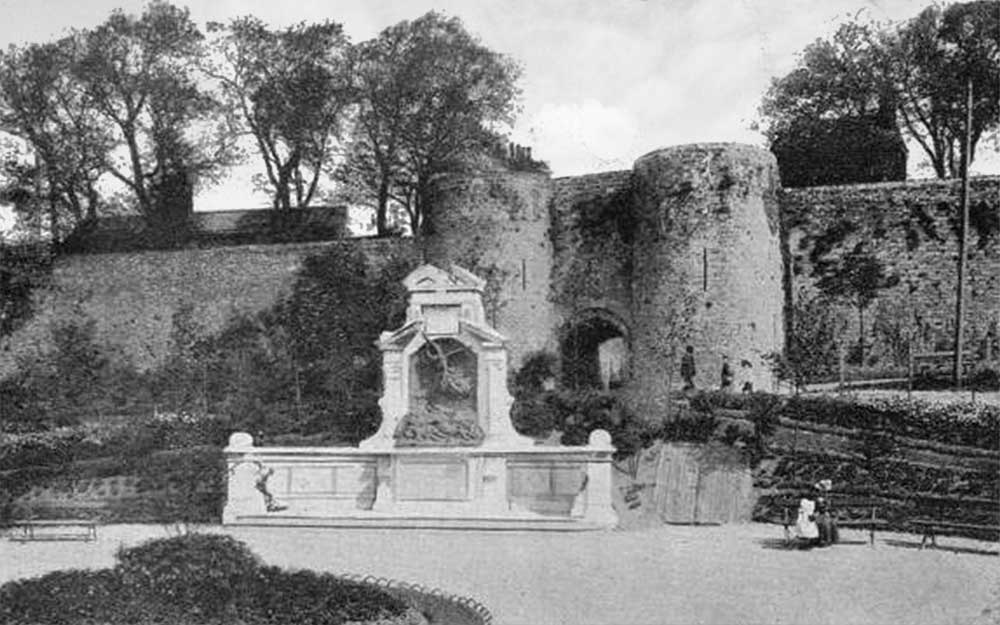

The present fortifications and site of the Roman encampment at Boulogne (see p. 91).

Armorica was called Britannia by Sulpicius Severus, but Sidonius Apollinarus, who flourished some time after, called the same country Armorica. It was not, however, unusual, as Carte points out, for the same people and the same country to be called by different names; for example, the Armorici and the Morini were one and the same people, whose names had the same signification—dwellers on the sea coast. (Carte, p. 16; Whitaker’s “Genuine History of the Briton,” pp. 216–219.)

As the historians just quoted are not concerned with the history of St. Patrick, but are simply tracing the origin and history of the Britons, their testimony is impartial.

Even Camden admits that Dionysius places the Britons on the maritime coast of Gaul, and renders his verses into English:—

“Near the great pillars of the farthest land,

The old Iberians, haughty souls, command

Along the continent, where northern seas

Roll their vast tides, and in cold billows rise:

Where British nations in long tracts appear

And fair-haired Germans ever famed in war.”

The early existence of the Britons in Armorica did not depend on the settlement of the veteran Britons, who, having served under Constantine the Great, were rewarded by a gift of the vacant lands in Armorica, as William of Malmesbury narrates in his “History of the Kings”; or on the still larger settlement of Britons who fought for the usurper Maximus, which Ninius mentions, in the mysterious reference which embraced the whole country “from the Great St. Bernard in Piedmont to Cantavic in Picardy, and from Picardy to the western coast of France.” The latter settlement took place between the years 383 and 388. The British refugees, who fled in terror from the Picts, Scots, and Saxons, may indeed have added to the numbers of Britons in Gaul from time immemorial, but they certainly were not the first to give the name Britannia to that country.

Boulogne-sur-Mer: St. Patrick's Native Town - Paperback Edition

Boulogne-sur-Mer: St. Patrick's Native Town - Kindle Edition