Shoes and Footwear in Ancient Ireland

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVIII....continued

Foot-Wear.—The most general term for a shoe was bróg, which was applied to a shoe of any kind: it is still the word in common use. The bróg was very often made of untanned hide, or only half tanned, free from hair, and retaining softness and pliability like the raw hide.

This sort of shoe was also often called cuarán or cuaróg, from which a brogue-maker was called cuaránaidhe [cooraunee].

This shoe had no lift under the heel: the whole was stitched together with thongs cut from the same hide. But there was a more shapely shoe than the cuaran, made of fully tanned leather, having serviceable sole and heel, and often highly ornamented.

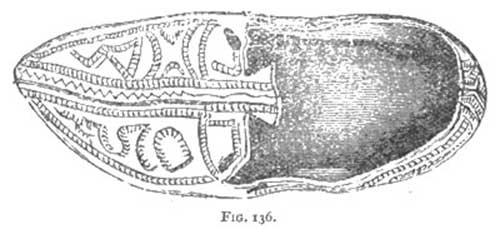

There are several specimens of such shoes in the National Museum, Dublin, of which one is represented here (fig. 136).

To this kind of shoe the two terms ass (pl. assa) and maelan were often applied; but these have long dropped out of use.

Most of the figures depicted in the Book of Kells and on the shrines and high crosses have shoes or sandals, though some have the feet bare. One wears well-shaped narrow-toed shoes seamed down along the instep, something like the shoe represented on last page (fig. 136), but much finer and more shapely.

Some have sandals consisting merely of a sole bound on by straps running over the foot: and in all such cases the naked toes are seen.

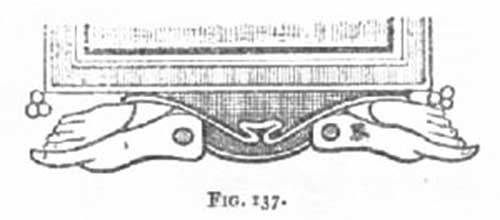

On many of the sandals there are what appear to be little circular rosettes just under or on the ankles, one on each side of the foot—perhaps mere ornaments.

They are seen in the figure of the angel, p. 386, supra; and more plainly in fig. 137 given here, also from the Book of Kells.

FIG.137. Small portion of panel in Book of Kells, showing sandals under feet, with rosettes. (Dr. Abbott's Reproductions).

In many of the most ancient Irish tales we often find it mentioned that persons wore assa or maelassa or shoes made of silver or of findruine (white bronze).

Such shoes or sandals must have been worn only on special or formal occasions: as they would be so inconvenient as to be practically useless in real everyday life.

As confirming this idea of temporary and exceptional use, we have in the National Museum a curious pair of (ordinary leather) shoes—shown in the illustration—connected permanently, so that they could only be used by a person sitting down or standing in one spot.

In whatever way and for whatever purpose the metallic shoes were used, they must have been pretty common, for many have been found in the earth, and some are now preserved in museums.

FIG.138. Pair of shoes permanently connected by straps: two soles and straps cut out of one piece. Most beautifully made. (From Wilde's Catalogue.)

There were tradesmen, too, who made and dealt in them, as is proved by the fact that about the year 1850 more than two dozen ancient bronze shoes were found embedded in the earth in a single hoard near the Giant's Causeway.

The finding of bronze shoes, and in such numbers, is a striking illustration of how the truthfulness of many old Irish records, that might otherwise be considered fabulous, is confirmed by actual existing remains.