Fasteners for Upper Garments in Ancient Ireland

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVIII....continued

Fasteners for Upper Garments.—The overgarments were fastened by brooches, pins, buttons, girdles, strings, and loops. Brooches will be treated of in next section.

Simple pins were generally ornamented, head, or shank, or both, as seen in the figures given on next page, of which the original are all in the National Museum, with many others.

Nether Garments.—The ancient Irish wore a trousers which differed in some respects from that worn at the present day. It generally reached from the hips to the ankles, and was so tight fitting as to show perfectly the shape of the limbs.

When terminating at the ankles it was held down by a slender strap passing under the foot, as seen in one of the figures in the Book of Kells.

Like other Irish garments it was generally striped or speckled in various colours.

Leggings (called ochra) of cloth or of thin soft leather were worn, probably as an accompaniment to the kilt.

FIG. 121. Showing the tight trews or trousers, with a fallainn or short cloak, dyed olive-green. (From a copy of Giraldus, A.D. 1200. Wilde's Catalogue.).

They were laced on by strings tipped with findruine or white bronze, the bright metallic extremities falling down after lacing, so as to form pendant ornaments.

There are many passages in our ancient literature showing that it was pretty usual with those engaged in war to leave the legs naked: a fashion perpetuated by the Scotch to this day.

This fashion is also indicated by such nicknames as Glúnduff (‘black-knee’), Glúngel (‘white knee’), &c., which were very common.

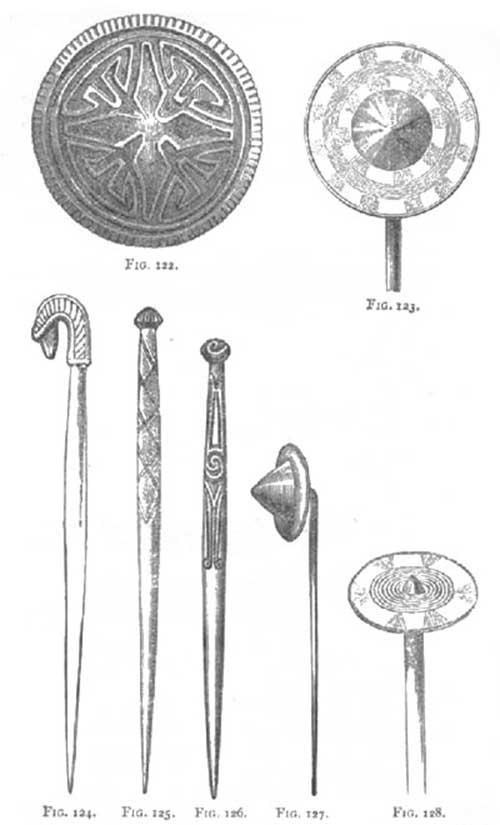

FIGS. 122-128. Bronze button and pins: all very ancient. Figure 122, a highly-decorated bronze button, enamelled in red and green, with a small metal fastening-loop at back, as on modern buttons. Figures 124, 125, 126, bronze pins. Figure 128, bronze pin, 13 1/2 inches with disk 2 3/4 inches in diameter. (All from Wilde's Catalogue).

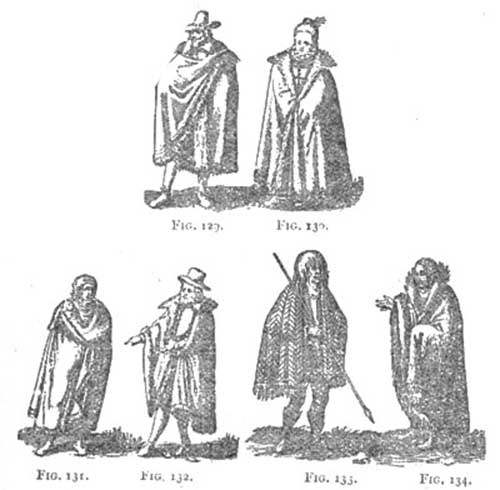

As illustrative of all that precedes, a series of costumes of the year 1600 are presented here.

FIGS. 129-134. Irish Costumes, A.D. 1600. (From Speed's map of Ireland: A.D. 1611). Figures 129 and 130, gentleman and lady of the high classes. Figures 131 and 132, persons of the middle rank. Figures 133 and 134, peasants.

Underclothing.—Both men and women wore a garment of fine texture next the skin. This is constantly mentioned in the tales, and, whether for men or women, is denoted by the word leine or lene [2 syll.], which is now the common Irish word for a shirt.

It was usually made of wool or flax: sometimes it was of silk, occasionally of satin, highly ornamented with devices in gold and silver thread, worked with the needle.

Girdles and Garters.—A girdle or belt (Ir. criss) was commonly worn round the waist, inside the outer loose mantle; and it was often made in such a way as to serve as a pocket for carrying small articles.

Sometimes a bossan or purse (also called sparan) was hung from it, in which small articles were kept, such as rings.

The girdles of chiefs and other high-class people were often elaborately ornamented and very valuable: worth from £40 to £100 of our money.

Garters were worn, sometimes for use and sometimes for mere ornament, or to serve both purposes. They were made of various materials according to the rank of the wearer: kings, chiefs, and ollaves of poetry often wore garters of gold.

Gloves.—That gloves were commonly worn is proved by many ancient passages and indirect references. They appear to have been common among all classes—poor as well as rich.

One of the good works of charity laid down in the Senchus Mór is “sheltering the miserable,” which the gloss explains, “to give them staves and gloves and shoes for God's sake.”

The evangelist depicted in the Book of Kells (fig. 118, p. 387, above) wears gloves, with the fingers divided as in our present gloves, and having the tops lengthened out beyond the natural fingers.

Rich people's gloves were often highly ornamented.

As to material: probably gloves were made, as at present, both of cloth and of animal skins and furs.

The importance and general use of gloves as an article of dress are to some extent indicated by their frequent mention and by the number of names for them.

The common word for a glove was lamann, which is still in use.

Head Gear.—The men wore a hat of a conical shape, without a leaf, called a barréd [barraid], a native word, of which the first syllable, barr, signifies top.

Among the peasantry, the men, in their daily life, commonly went bare-headed, wearing the hair long behind so as to hang down on the back, and clipped short in front.

Sometimes men, even in military service, when not engaged in actual warfare, went bare-headed in this manner.

In the panels of one of the crosses at Clonmacnoise are figures of several soldiers: and while some have conical caps, others are bare-headed.

Camden describes Shane O'Neill's galloglasses, as they appeared at the English court in the sixteenth century, as having their heads bare, their long hair curling down on the shoulders and clipped short in front just above the eyes.

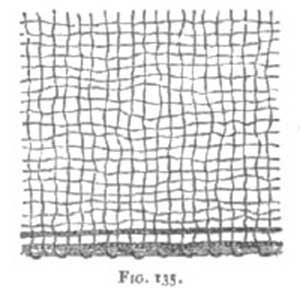

FIG. 135. Portion of "a light gauzy woollen veil, of most delicate texture." (Wilde). Found on the body of a woman. (From Proc. Roy. Ir. Acad.).

Married women usually had the head covered either with a hood (caille, pron. cal-le) or with a long web of linen wreathed round the head in several folds. The veil was in constant use among the higher classes, and when not actually worn was usually carried, among other small articles, in a lady's ornamental hand-bag.