The Cashel and Crannog

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVI....continued

The cashel was a strong stone wall round a king's house, or round a monastery; of uncemented stones in pagan times, but often built with mortar when in connexion with monasteries. The caher was distinguished from the cashel by being generally more massive in structure, with much thicker walls. The cahers are almost confined to the south and west of Ireland. Buildings like our cahers are also found on the Continent.

That the wooden dwelling-houses were erected within the enclosing lis, or rath, is abundantly evident from the records. Queen Maive Lederg (not Queen Maive of Croghan) is recorded to have built the rath near Tara, now called from her, Rath-Maive: "and she built a choice house within that rath." There were often several dwelling-houses within one large rath: inside the great rath at Emain there were at least three large houses, with others smaller: the Rath-na-Righ at Tara had several houses within it: and in the romantic story of Cormac in Fairyland, we are told that he saw "a very large kingly dún which had four houses within it."

The rampart enclosing a homestead was usually planted on top with bushes or trees, or with a close thick hedge, for shelter and security: or there was a strong palisade on it. Lisses and raths such as we see through the country are generally round or oval: but they are occasionally quadrangular. Vitrified forts, i.e. having the clay, gravel, or stone of the rampart converted into a coarse glassy substance through the agency of enormous fires, are found in various parts of Ireland as well as in Scotland: and similar forts are still to be seen in several parts of the Continent.

Immediately outside the outer door of the rath was an ornamental lawn or green called aurla, urla, or erla, which was regarded as forming part of the homestead: "then queen Maive went out through the door of the liss into the aurla, and three times fifty maidens along with her." Beside the dún or lis, but beyond and distinct from the aurla, was a large level sward or green called a faithche [faha], which was chiefly used for athletic exercises and games of various kinds. Some idea of its size may be formed from the statement in the law that the faithche of a brewy extends as far as the voice of a bell (i.e. of the small bell of those times) or the crowing of a cock can be heard. The higher the rank of the chief the larger the faithche.

FIG. 87. Carlow Castle in 1845: believed to have been erected by Hugh de Lacy who was appointed Governor of Ireland in 1179. One of the Anglo-Norman castles referred to at p. 313, below. (From Mrs Hall's Ireland).

The haggard for grain-stacks, which was always near the homestead, was called ithlann, from ith, 'corn.' At a little distance from the dwelling it was usual to enclose an area with a strong rampart, into which the cattle were driven for safety by night. This was what was called a badhun [bawn], i.e. 'cow-keep,' from ba, pl. of bo, 'a cow,' and dún. This custom continued down to a late time.

The outer defence, whether of clay, or stone, or timber, that surrounded the homestead was generally whitened with lime—a practice often referred to in old Irish literature. The great ramparts of Tara must have shone brilliantly over the surrounding plain: for it is called "White-sided Tara," in some old Irish writings.

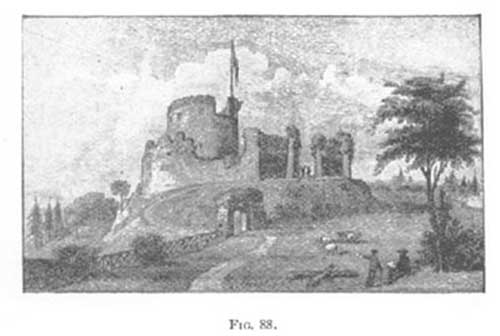

FIG. 88. Dundrum Castle, near Newcastle,County Down. Built at end of 12th century by John de Courcy, on the very site of the old Irish fortress called Dun Rury, which covered the summit of the rock. The great earthworks belonging to the original dún still remain at the base of the rock at one side, but are not seen in this figure. (from Kilk. Archaeol. Journ.).

In modern times, when the native knowledge of Irish history and antiquities had greatly degenerated, and the light of our own day had not yet dawned, many writers attributed the ancient Irish raths and duns to the Danes, so that it became the fashion to call them "Danish raths or forts"; but this idea has been long since exploded.

The Anglo-Normans built stone castles in Ireland according to their fashion: and not infrequently they selected the very site, or the very vicinity, of the old Irish fortresses: for an Anglo-Norman had at least as keen an eye for a good military position as an old Irish warrior. Accordingly the circumvallations of the ancient native forts still remain round the ruins of many of the Anglo-Norman castles. It is to be observed that the Irish began to abandon their earthen forts and build stone castles—many of them round like the older earthen forts and cahers—shortly before the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in 1169: but this was probably in imitation of their warlike neighbours.

Crannoges .—For greater security, dwellings were often constructed on artificial islands made with stakes, trees, and bushes, covered with earth and stones in shallow lakes, or on small, flat natural islands if they answered. These were called by the name crannóg [crannoge], a word derived from crann, 'a tree,' as they were constructed almost entirely of wood. Communication with the shore was carried on by means of a small boat, commonly dug out of one tree-trunk. Usually one family only, with their attendants, lived on a crannoge island: but sometimes several families, each having a separate wooden house. Where a lake was well suited for it—pretty large and shallow—several islands were formed, each with one or more families, so as to form a kind of little crannoge village.

Crannoge dwellings were in use from the most remote prehistoric times; they are very often noticed, both by native Irish and by English writers, and they continued down to the time of Elizabeth. Great numbers of crannoges have of late years been explored, and the articles found in them show that they were occupied by many generations of residents. In most of them rude "dug-out" boats have been found, many specimens of which are preserved in the National Museum, Dublin, and elsewhere. Lake-dwellings similar to the Irish crannoges were in use in early times all over Europe, and explorers have examined many of them, especially in Switzerland.