Defence of Ancient Irish Houses

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER XVI....continued

3. Outer Premises and Defence.

The homesteads had to be fenced in to protect them from robbers and wild animals. This was usually done by digging a deep circular trench, the clay from which was thrown up on the inside. This was shaped and faced; and thus was formed, all round, a high mound or dyke with a trench outside, and having one opening for a door or gate. Whenever water was at hand, the trench was flooded as an additional security: and there was a bridge opposite the opening, which was raised, or closed in some way, at night. The houses of the Gauls were fenced round in a similar manner. Houses built and fortified in the way here described continued in use in Ireland till the thirteenth or fourteenth century.

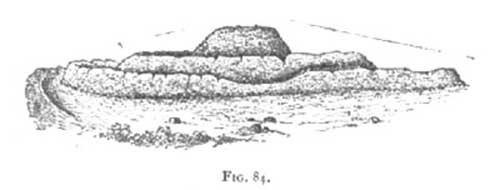

These old circular forts are found in every part of Ireland, but more in the south and west than elsewhere; many of them still very perfect—but of course the timber houses are all gone. Almost all are believed in popular superstition to be the haunts of fairies. They are now known by various names—lis, rath, brugh, múr, dún, moat, caiseal [cashel], and cathair [caher]: the cashels, murs, and cahers being usually built of stone without mortar. These are generally the very names found in the oldest manuscripts. The forts vary in size from 40 or 50 feet in diameter, through all intermediate stages up to 1500 feet: the size of the homestead depending on the rank or means of the owner. Very often the flat middle space is raised to a higher level than the surrounding land, and sometimes there is a great mound in the centre, with a flat top, as seen in the illustration, on which the strong wooden house of the chief stood. Forts of this exact type are still to be seen in England, Wales, and Scotland, as well as in various parts of the Continent; but they are most numerous in Ireland. Round the very large forts there are often three or more great circumvallations, sometimes as many as seven. The "moat or fort of Kilfinnane," here figured, has three.

FIG. 84. The great Moat of Kilfinnane," Co.Limerick, believed to be one of the seats of the kings of Munster. Total diameter 320 feet. (From a drawing by the author, 1854).

A dún, sometimes also called dind, dinn, and dingna, was the residence of a Ri [ree] or king: according to law it should have at least two surrounding walls with water between. Eound the great forts of kings or chiefs were grouped the timber dwellings of the fudirs and other dependents who were not of the immediate household, forming a sort of village.

In most of the forts, both large and small, whether with flat areas or with raised mounds, there are underground chambers, commonly beehive-shaped, which were probably used as storehouses, and in case of sudden attack as places of refuge for women and children. In the ancient literature there are many references to them as places of refuge. The Irish did not then know the use of mortar, or how to build an arch, any more than the ancient Greeks; and these chambers are of dry-stone work, built with much rude skill, the dome being formed by the projection of one stone beyond another, till the top was closed in by a single flag.

FIG. 85. Staigue Fort in Kerry. Of stones without mortar. External diameter 114 feet: wall 13 feet thick at bottom, 5 feet at top. (From Wood Martin's Pagan Ireland, and that from Wilde's Catalogue).

Where stone was abundant the surrounding rampart was often built of dry masonry, the stones being fitted with great exactness. In some of these structures the stones are very large, and then the style of building is termed cyclopean. Many great stone fortresses of the kind described here, usually called caher, Irish cathair, still remain near the coasts of Sligo, Galway, Clare, and Kerry, and a few in Antrim and Donegal: two characteristic examples are Greenan-Ely, the ancient palace of the kings of the northern Hy Neill, in Donegal, and Staigue Fort near Sneem in Kerry. The most magnificent fortress of this kind in all Ireland is Dun Aengus on a perpendicular cliff right over the Atlantic Ocean on the south coast of Great Aran Island.

At the most accessible side of some of these stone cahers, or all round if necessary, were placed a number of large standing stones firmly fixed in the ground, in no order—quite irregular—and a few feet apart. This was a very effectual precaution against a sudden rush of a body of assailants. Beside some of the existing cahers these stones, or large numbers of them, still remain in their places (as shown in fig. 86).

FIG. 86. Dun-Aengus on Great Island of Aran, on the edge of a cliff overhanging the sea: circular caher without mortar: standing stones intended to prevent a rush of a body of enemies. (From Wilde's Lough Corrib).