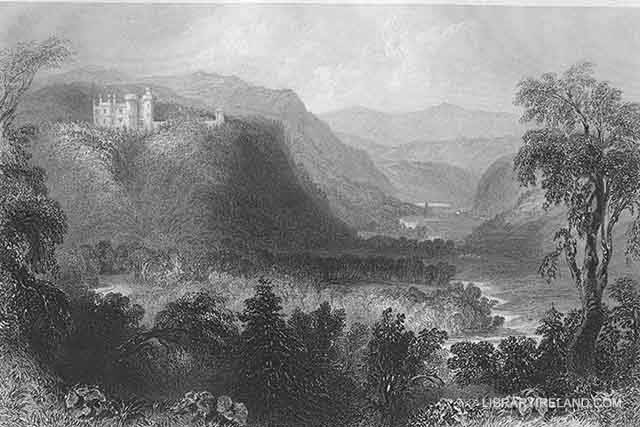

Glenmalure and Castle Howard, County Wicklow

Quitting the solitary and awe-inspiring Glendalough, the tourist intending to visit the delightful Vale of Avoca, proceeds by the military road to GLENMALURE, a beautiful valley, through which for several miles winds the Avonbeg, one of the rivers which afterwards combine in the Meeting of the Waters. The character of this glen is altogether different from the picturesque beauty of the wooded Dargle, or the softer features of the Glen of the Downs; its aspect is wild and impressive, the rude and barren rocks which rise abruptly on either hand giving a savage grandeur to the scene. THE HEAD OF GLENMALURE, where the waters of a small stream, flowing down the precipitous face of a steep mountain, form the Ess Fall, is especially striking, and merits the praise of a modern tourist, who asserts that it is by far the finest of the Wicklow Glens, and, with the exception of the Killeries in Connemara, is not to be equalled in the kingdom.

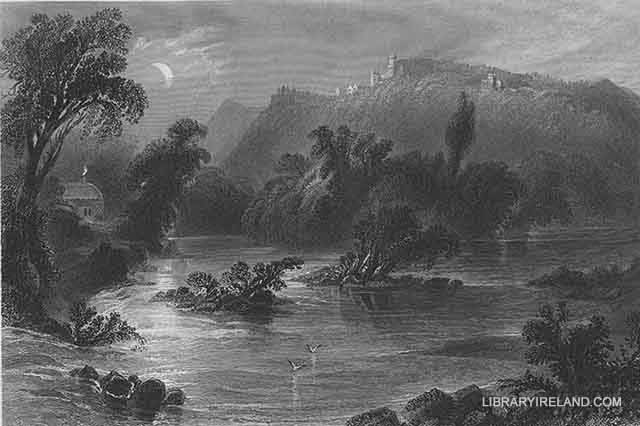

The outlet of Glenmalure, proceeding towards Rathdrum, is extremely pleasing: the valley expands, the hills slope gently away, and being wooded down to the banks of the river, the features of the landscape are not so wild and rugged as in the upper part of the glen. At the junction of Glenmalure with the Vale of Avoca, the most striking object is CASTLE HOWARD, the residence of Mrs. Howard, picturesquely perched on the brow of a lofty eminence, apparently upheld by the:ops of the trees, for from the towers to the river side it is one mass of luxuriant foliage. Directly below this romantic structure, the Avonbeg and the Avonmore, stealing forth from their secluded glens, unite their streams; and here the Vale of Avoca, which stretches from hence to the sea at Arklow, may be said to commence.

The confluence of these rivers is generally termed THE MEETING OF THE WATERS. Nature has here scattered her charms with a liberal hand: waving woods, clear waters, and verdant shores, combine to render the scene one of surpassing softness and beautiful tranquillity. "It is not a scene," says a late writer, "which a poet or painter would visit if he wished to elevate his imagination by sublime views of nature, or by images of terror; but if he desired to represent the calm repose of peace and love, he would choose this glen as their place of residence." No language could adequately convey to the reader a faithful picture of the serene beauty of this enchanting valley, but the emotions which the contemplation of them excites in the human breast, has been elegantly described by the graceful pen of Ireland's bard. Who does not remember that warm effusion of his early muse, consecrated to "The Meeting of the Waters," commencing with the following stanza?—

"There is not in the wide world a valley so sweet,

As the vale in whose bosom the bright waters meet;

Oh, the last rays of feeling and life must depart,

Ere the bloom of that valley shall fade from my heart."

From "The Meeting of the Waters," the river pursues its devious course to the sea through a fertile valley, whose mountainous sides are thrown into an endless variety of lovely pictures by the irregularity of their positions. These mountainous ridges are covered with the thick foliage of the oak,[45] and are richly pictorial in heaths, furze, and other upland vegetation. Further onward the vale gradually expands into broad and verdant slopes, dotted at intervals with white cottages, through which the river glides gently towards the sea, whose blue waters make a noble boundary to a combination of the grandest and softest scenery which nature has ever produced.

NOTE

[45] Ireland was once celebrated for her oak woods, and, according to the authority of Spenser, the county of Wicklow, so recently as the reign of Elizabeth, was greatly encumbered with a redundance of wood. The oak woods of Shillelah (a barony so called) conferred that universally-known appellation on the redoubtable cudgel of the Irish peasant, the toughness of which can only be equalled by the heads to which it is so frequently applied in the little scrimmages that occur at the fairs, patrons, and merry-makings through the country. It was these woods that supplied the architect of Westminster Hall with the oak-timber of which the roof of that noble and venerable edifice was constructed. But the glories of Shillelah are departed; a few straggling trees are all that now remain to perpetuate the wooded pride of that famous district.