Abbey of Mucruss

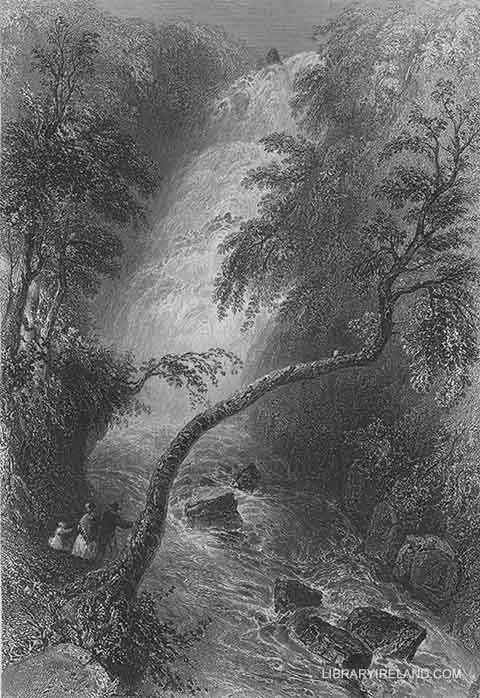

From Innisfallen I pulled over to Mucruss, the charming demesne of Mr. Herbert, which stretches from the foot of the Turk Mountain along the eastern borders of the Middle and Lower Lakes. The old abbey of Irrelagh or Mucruss stands on a slight eminence, on the right of the road leading to the mansion-house, and as seen partially through the trees, is an object of the highest picturesque beauty. A well-kept, good road, lying through very highly cultivated park-scenery, conducts to the abbey, of which I made a cursory examination, deferring to another day the pleasure of a leisurely survey of these beautiful ruins. Having ordered my boat to meet me at the head of the Upper Lake, I took a car and proceeded by a capital road along the shore to TURK CASCADE, a very picturesque fall, formed by the Devil's Stream in its descent from Mangerton. The waters are precipitated in a sheet of white foam over a projection of the mountain, from a height of sixty or seventy feet. After breaking on the rocks in mist and spray, the torrent resumes its impetuous course through a deep, narrow ravine, and soon mingles with the waters of the lake. Mr. Herbert has a pretty cottage, romantically situated on the borders of the ravine, amidst young plantations and tastefully arranged pleasure-grounds.

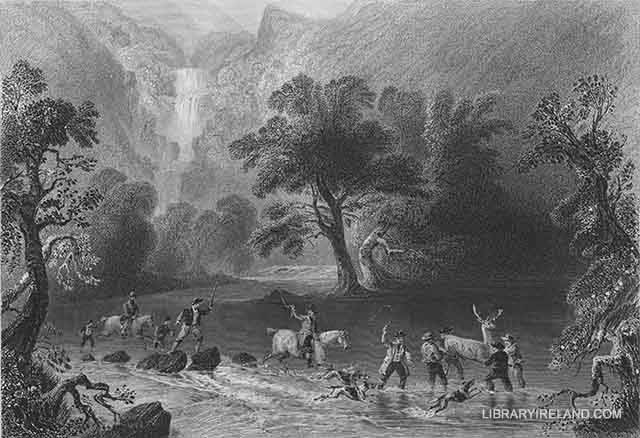

After ascending a winding path to a lofty spot above the cascade, where I got a very fine view of the LOWER and TURK LAKES, I resumed my route along the smooth road leading past Mucruss Cottage, admiring the splendid purple tints on the mountain sides, and the wonderful variety in the shapes and groupings of the noble mountains around me. On reaching a very spacious tunnel, which lets the road through a cliff on the shore, I found my boatmen sitting on the rocks, engaged with a wooden noggin of goat's milk and a bottle of whiskey. Leaving them to their agreeable employment, I drove on a mile further to see the DERRICUNNEHEY CASCADE. The driver stopped at the ruins of a small cottage, situated on a stream, which I crossed by a rustic bridge, and obtained an excellent view of a fine waterfall, some thirty feet high, surrounded with picturesque adjuncts of wood and rock. The artist whose beautiful drawings embellish this work, was fortunate enough to witness the taking of a stag just below the Derricunnehey Cascade. Of this sport, for which Killarney is so famous, Mr. Wild gives a graphic account.

"On the day preceding the hunt, those preparations are made which are thought best calculated to ensure it a happy issue. An experienced person is sent up the mountain to search for the herd, and watch its motions in patient silence till night comes on. The deer which remains the most aloof from its companions is carefully observed, and marked as the object of pursuit, and it is generally found at the dawn of the ensuing morning in the vicinity of the evening haunt. Before the break of day the dogs are conducted up the mountain as silently and secretly as possible, and are kept coupled until some signal, commonly the firing of a small cannon, announces that the party commanding the hunt has arrived in boats at the foot of the mountain; then the dogs are loosed, and brought upon the track of the deer. If the business previous to the signal has been silently and orderly conducted, the report of the cannon, the sudden shouts of the hunters on the mountain which instantly succeed it, the opening of the dogs, and the loud and continued echoes along an extensive region of woods and mountains produce an effect singularly grand.

"Tremble the forest round; the joyous cries

Float through the vales; and rocks, and woods, and hills

Return the varied sounds."

The deer, upon being roused, generally endeavours to gain the summit of the mountains, that he may the more readily make his escape across the open heath to some distant retreat. To prevent this, numbers of people are stationed at intervals along the heights, who by loud shouting terrify the animal, and drive him towards the lake. At the last hunt which I attended, a company of soldiers were placed along the mountain-top, who, keeping up a running fire, effectually deterred him from once ascending. The hunt, however, begins to lose its interest after the first burst, and the ear becomes wearied with the incessant shouts which drown the opening of the hounds, and the echoes of their mellow tones. The ruggedness of the ground embarrasses the pursuers; the scent is followed with difficulty, and often lost altogether, or only resumed at the end of a long interval: much confusion also arises from the emulous efforts of the people on the water to follow the course of the hunt, especially if it should take a direction towards the Upper Lake, when the contending boats are frequently entangled among the rocks and shoals of the river which leads to it.

Those who attempt to follow the deer through the woods are rarely gratified with a view, and are often excluded from the grand spectacle of his taking the sail, or, in other words, plunging into the lake. It is therefore generally recommended to remain in a boat; and those who have the patience to wait as long as five or six hours are seldom disappointed. I was once gratified by seeing the deer run for nearly a mile along the shore, with the hounds pursuing him in full cry. On finding himself closely pressed, he leaped boldly from a rock into the lake, and swam towards one of the islands; but terrified by the approach of the boats he returned, and once more sought for safety on the main shore; soon afterwards, in a desperate effort to leap across a chasm between two rocks, his strength failed him, and he fell exhausted to the bottom. It was most interesting to behold the numerous spectators who hastened to the spot,—ladies, gentlemen, peasants, hunters, combined in various groups around the noble victim as he lay extended in the depth of the forest. The stag, as is usual on these occasions, was preserved from death."