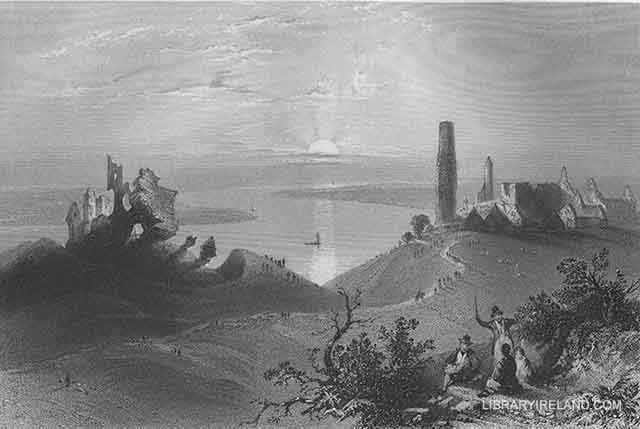

Clonmacnoise

"We had neither time nor patience to remain long on a remote hill, while the ruins of CLONMACNOISE were within ten minutes' walk of us, so we proceeded to the first ruin, which lies separate from all the rest, on the northern side of the churchyard, the large field or common on which the patron is held intervening. Little remains of this church but a beautiful arch of the most florid and ornate Gothic workmanship, forming the opening from the body of the church into the chancel: it now totters to its fall—it is even surprising that it does not tumble; and I suspected that it would long ago have fallen a victim to the elements or to the barbarous violence of the people, were it not that it is considered as part of an expiating penance for the pilgrim to creep on his bare knees under this arch while approaching the altar-stone of this chapel, where sundry paters and aves must be repeated as essential to keeping the station. Adjoining this is a holy stone on which St. Kieran sat, and the sitting on it now, under the affiance of faith, proves a sovereign cure for all epileptic people.

"Here is the largest enclosure of tombs and churches I have anywhere seen in Ireland. What a mixture of old and new graves! Modern inscriptions recording the death and virtues of the sons of little men, the rude forefathers of the surrounding hamlets;—ancient inscriptions in the oldest forms of Irish letters, recording the deeds and the hopes of kings, bishops, and abbots, buried a thousand years ago, lying about broken, neglected, and dishonoured, what would I give could I have deciphered! I should have been glad, had time allowed, to be permitted to transcribe them. And what shall I do with all those ancient towers, and crosses, and churches, without a guide? I looked around: there were many people in the sacred inclosure; some kneeling in the deepest abstraction of devotion at the graves of their departed friends,— the streaming eye, the tremulous hand, the bowed-down body, the whole soul of sorrowful reminiscence and of trust in the goodness of the God of spirits, threw a sacred solemnity about them, that few indeed, though counting their act superstitious, would presume to interrupt; he who would venture so to do, must be one indeed of little feeling. I saw others straggling through the place—some half intoxicated, sauntering or stumbling over the gravestones—others hurrying across the sacred inclosure, as if hastening to partake of the last dregs of debauchery in the tents of the patron-green.

"After looking about vaguely for some time, this church of St. Kieran was what caught my particular attention. It was extremely small, more an insignificant oratory than what could be called a church;—a tall man could scarcely lie at length in it; a mason would have contracted to build its walls for a week's wages; yet this, my mendicant guide said, was the old church of St. Kieran. The walls had all gone away from their foundations; they had collapsed together, and presented a picture of desolation without grandeur. Beside it was a sort of cavity or hollow in the ground, as if some persons had lately been rooting to extract a badger or a fox; but here it was that the people, supposing St. Kieran to be deposited, have rooted diligently for any particle of clay that could be found, in order to carry home that holy earth, steep it in the water, and drink it; and happy is the votary who is now able amongst the bones and stones to pick up what has the semblance of soil, in order to commit it to his stomach as a means of grace, or as a sovereign remedy against diseases of all sorts.