Library at Trinity College Dublin - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter 1: Ireland’s Eye … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

The library is very rich in specimens of early Irish illuminated MSS., and these, together with many other very precious literary treasures, have their home in what is called the Manuscript Room. This apartment is on the ground floor, and can only be seen by visitors who are able to secure the presence of the Librarian or one of the Fellows of the College.

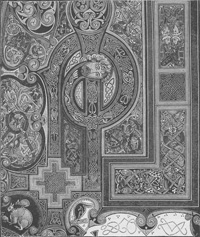

The most famous of these literary treasures are exhibited in cases which stand on the floor of the great library, and among these the highest place is held by the Book of Kells. This is one of the finest MSS. in Europe, and as a specimen of Irish illumination and writing has no rival. It dates from the time when Ireland, under the name of Scotia, was famous throughout Europe for her schools and for her missionary enterprise. It was the product of the age which sent Columba to Iona, Cuthbert to England, and Columbanus to Gaul. It is a copy of the Gospels, and takes its name from the fact that it once belonged to the monastery at Kells in Meath. The date has to be fixed by internal evidence, and the best authorities now lean to the view that it was written about the end of the sixth century. The Irish Annals record that in the year 1006 it was stolen from the church at Kells, that it was famous for its cover, and that it was found after forty nights and two months, 'after its gold had been taken from it, and with sods over it.' The monastery of Kells became Crown property in 1539, and the great MS. fell into the hands of Gerald Plunket of Dublin. In the seventeenth century Usher became its owner, and with his other books, in 1661, it found a permanent and safe home where it has since dwelt. To it, as to so many of its brethren, time and the binder have proved cruel foes. Although it still contains 344 folios, it has lost leaves at both the beginning and end; and when, in the early part of this century, it was rebound, the margins were sadly mutilated. But time has done little to destroy the wondrous beauty of colouring in its marvellous illuminations, and its wealth and richness of design are still the wonder of every competent observer. It is the most superb example of this branch of early Irish art. Professor Westwood thus describes the special features of this book as illustrative of the early Irish style of MS. adornment:

'Ireland may be justly proud of the Book of Kells—a volume traditionally asserted to have belonged to St. Columba, and unquestionably the most elaborately executed MS. of so early a date now in existence, far excelling in the gigantic size of the letters at the commencement of each Gospel, the excessive minuteness of the ornamental details crowded into whole pages, the number of its very peculiar decorations, the fineness of the writing, and the endless variety of its initial capital letters, the famous Gospels of Lindisfarne in the Cottonian Library. But this manuscript is still more valuable on account of the various pictorial representations of different scenes in the life of our Saviour, delineated in the genuine Irish style, of which several of the manuscripts of St. Gall and a very few others offer analogous examples. The numerous illustrations of this volume render it a complete storehouse of artistic interest. The text itself is far more extensively decorated than in any other now existing copy of the Gospels.' [1]

'Especially deserving of notice,' continues Professor Westwood, 'is the extreme delicacy and wonderful precision united with an extraordinary minuteness of detail with which many of these ancient manuscripts were ornamented. I have examined with a magnifying-glass the pages of the Gospels of Lindisfarne and Book of Kells, for hours together, without ever detecting a false line or an irregular interlacement; and when it is considered that many of these details consist of spiral lines, and are so minute as to be impossible to have been executed without a pair of compasses, it really seems a problem not only with what eyes, but also with what instruments they could have been executed. One instance of the minuteness of these details will suffice to give an idea of this peculiarity. I have counted in a small space, measuring scarcely three quarters of an inch, by less than half an inch in width, in the Book of Armagh, not fewer than one hundred and fifty-eight interlacements of a slender ribbon pattern, formed of white lines edged by black ones upon a black ground.'[2]

'The introduction of natural foliage in this MS. is another of its great peculiarities, whilst the intricate intertwinings of the branches is eminently characteristic of the Celtic spirit, which compelled even the human figure to submit to the most impossible contortions.'[3]

The following inscription, in a minute hand, is still partly legible in a small semicircular space at the head of the columns on folio 4 verso. 'This work doth pass all mens conying that doth live in any place.

'I doubt not there … anything but that the writer hath obtained God's grace, GP.' On the verso of folio 344 is the following entry:—'I, Geralde Plunket, of Dublin, wrot the contents of every chapter; I mean where every chapter doth begin, 1568. The boke contaynes tow hundreth v and iii leaves at this present xxvii August 1568.'

Under this is written by Usher, who was Bishop of Meath from 1621 to 1624: 'August 24, 1621. I reckoned the leaves of this and found them to be in number 344. He who reckoned before me counted six score to the hundred.'[4]

NOTES

[1] National MSS. of Ireland, by John T. Gilbert, p. 14.

[2] Ibid. p. 20.

[3] Ibid. p. 15.

[4] National MSS. of Ireland, pp. 20, 21.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »