Trinity College Dublin - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter 1: Ireland’s Eye … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

The foundation of Trinity College dates from 1592, and the institution began the work of teaching in 1593 as 'the College of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity near Dublin,' in the buildings of the Augustinian monastery of All Hallows. During the reigns of James I. and Charles I. it was richly endowed with confiscated lands. Many private benefactors enriched it. James I. conferred also the privilege it still enjoys of sending two members to Parliament. It was not until 1792 that a Roman Catholic could there take a degree, and not until 1873 could any member of that communion enjoy any part of the rich endowments possessed by the College.

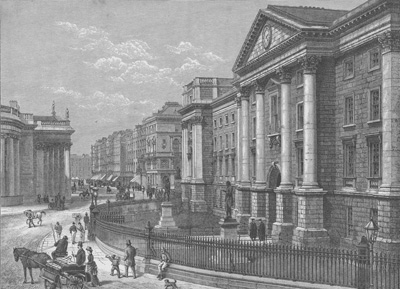

The facade facing College Green is somewhat heavy and sombre. It is very massive, and is principally built of Portland stone; but it at once arrests the attention of the passer-by, and the effect is by no means unpleasing. Passing between the statues of Burke and Goldsmith which flank the entrance, the visitor is admitted into a spacious quadrangle, in the centre of which stands a tall, handsome bell-tower, built of granite. On his right hand stands the Examination Hall or Theatre, and on the left the Chapel, with the Dining Hall as its next neighbour. Both Halls are enriched with portraits of famous students and graduates.

But it is to the right of the bell tower that most visitors make their first pilgrimage, for there stands the handsome range of buildings containing the Library. It is included among the five great libraries of the kingdom entitled to a copy of every book published in Great Britain and Ireland. The structure, from an architectural point of view, is plain and unpretending, and yet, withal, possesses a dignity of its own, and a certain fitness as the home of a great literary collection. The ground floor consists chiefly of an arcade, and the library building occupies the rest of the structure. The main apartment is the splendid gallery containing the bulk of the books. This is 210 feet long, 41 feet wide, and 40 feet high. The wood is dark, old oak, and along each side are recesses placed at right angles to the main axis of the room, filled with shelves, and arranged so as to combine very happily architectural effect with economy of space. A gallery, placed about twenty feet above the level of the floor, runs round the room, and the best view of this magnificent chamber can be obtained from the end of this gallery immediately over the entrance. The visitor, if at all literary in his sympathies, cannot fail to be charmed as his eye travels down the whole length of the room. The long vista, the lights streaming across from the windows at the end of each recess, the lofty arched roof, the apparently numberless bookshelves and books, the comfortable tables below with their busy readers, the cases full of priceless MSS., the long rows of gleaming marble busts of distinguished literary men of all ages and lands, the time-worn volumes and the richly carved and deep-toned wood, both alike eloquent of age—all these combine not only to delight the eye, but also at once to stimulate and to satisfy one's sense of literary fitness. A feeling of content that such a splendid library should be so superbly housed steals over the observer.

There are many matters in Ireland wherein ordinary courses of procedure seem to be reversed. The origin of Trinity College Library is an illustration in point. In various countries and in all ages scholars and lovers of literature have had to bewail the ravages in the way of MS. and book destruction caused by war. Yet it is out of warfare that this great library appears to have sprung. In 1603 the Spaniards were defeated at the battle of Kinsale by the English and Irish. The victors in their enthusiasm resolved to erect some permanent monument of their success; they collected among themselves the sum of £1,800 and—would that their example had found many imitators!—decided to expend the money in the purchase of books, and present them as the nucleus of a library to the College at Dublin, then completing its first decade. Archbishop Usher was appointed to expend the money, and few of the many tasks he performed during his life can have been so congenial. Since his day the collection has grown and grown until now it ranks as one of the largest in Europe. It can claim the Bodleian as a twin brother, for while Usher was spending his soldiers' money in London, he met there Sir T. Bodley, who was purchasing books for his Oxford collection.

Usher's own library, one which embraced manifold treasures in its 10,000 volumes, found here a permanent home. At the eastern end of the library is a handsome room, 52 feet long, 26 wide, and 22 high, containing what is known as the Fagel Library, once the property of a gentleman named Fagel, Pensionary of Holland, comprising 17,000 volumes, and purchased for £8,000.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »