The May-Day Festival in Ireland

From Ireland: Her Wit, Peculiarities and Popular Superstitions

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Contents | Next Chapter »

CHAPTER II...concluded

The May Day rhymes of the Irish peasantry are almost forgotten, and, in a few years hence, it is more than probable that a single verse of them will not live in the recollection of the people. They were often repeated in Irish; but the following scraps of a long, rude doggerel, which we possess, was the most general English version employed in Connaught, particularly in the counties of Roscommon and Galway:—

"This morning as the sun did rise,

We dressed the pole you to surprise;

With our fiddle and our pipes so gay,

To bring you good cheer on the first of May."

Several of the verses are but a paraphrase of the mummers and wren-boy rhymes. After describing "the treat" they expected, and hinting that—

"If it is but of the small,

It wont agree with the boys at all."

They added—

"'Tis then we'll dance and drink away,

And our pole and May bush thus display,

Until his fine lady to us will say,

Boys, 'tis time for you to go away;"Then we'll take off our hats and give three cheers,

Praying she may live these fifty years,

And off we'll go without delay,

Playing the tune called 'The First of May.'"

The sweet old air of "The Summer is Coming," to which Moore has written the song of "Rich and rare were the gems she wore," is what was generally repeated, but we can only procure a single verse of it: —

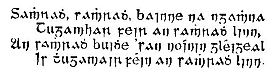

Summer! Summer! the milk of the heifers,

Ourselves brought the summer with us,

The yellow summer and the white daisy,

And ourselves brought the summer with us.

We remember a half-witted, purblind creature, known by the soubriquet of Saura Llynn, walking through the town of Castlerea upon May morning, playing on an old, rude bagpipe, with May flowers round his hat, and chanting this song, of which we have given above a verse in the original, the burden of which was: —

"Saura! Saura! bonne na Gauna,

Hugamur fain au Saura linn."

The summer was coming;—as soon as this half fool appeared, it was the general signal for all the idle boys and all the May bushers to flock round him like swallows after a hawk, so that by the time he had reached the centre of the village, he presented in his train a motley crowd. When last we heard of this poor fellow, who generally came to us from the extreme west, the only portion of his pipes which remained was the chanter, with his mouth applied to which, he used to blow a terrific squeal, then flourish it above his head, leap forwards in maniacal excitement and shout a few disjointed verses of the well-known song.

We find but slight traces of pantomime or theatrical representation among our May sports. In the south, the Mayers of former times had the hobby-horse as part of the procession; but that part of the ceremony was evidently an English importation, which has long since been lost. From Monaghan we have a graphic account of a somewhat similar proceeding; there the girls dressed up a churn-dash as a "May babby," like the Breedeogue at Candlemas—and the men, a pitchfork, with a mask, horse's tail, a turnip head, and ragged old clothes, as a "May boy;" but these customs have, we believe, long since become quite obsolete, as well as the following, described by Valiancy, in his "Inquiry into the First Inhabitants of Ireland:"—"In some parts, as the counties of Waterford and Kilkenny, the brides married since the last May Day are compelled to furnish the young people with a ball covered with gold lace, and another with silver lace, finely adorned with tassels; the price of these sometimes amounts to two guineas." These balls were, he says, "suspended in a hoop ornamented with flowers."

In the county of Meath, and throughout Fingal, it is customary for several boys and girls to go forth in gangs to seek for service on May morning, and particularly on the Sunday following, called there Sonnoughing Sunday, each one carrying some emblem of their peculiar calling; the girls always holding in their hands peeled switches or white wands; the men having something indicative of their employment—a carter a whip, a ploughboy a goad, a thresher a flail, or boulteen, and a herd a wattle, with a knob or crook on the end of it; or a hazel or round-tree rod, its extremity burned in the May bonfire, as a lucky staff wherewith to drive the cattle.

Certain legends relating to May Day attach to particular localities, as that of O'Donoghoe at Killarney, thus described by Crofton Croker: "On the first of May, in the morning, when the sun is approaching the summer solstice, the Irish hero, O'Donoghue, under whose dominion the golden age formerly reigned upon earth, ascends, with his shining elves, from the depths of the Lake of Killarney, and with the utmost gaiety and magnificence, seated on a milk-white steed, leads the festive train along the water. His appearance announces a blessing to the land, and happy is the man who beholds him."[20] "The Motty's Stone"[21] comes down from the Connery mountain every May morning to bathe in the Meeting of the Waters. Our good friend, Mr. R. Dowden, R. of Cork, informs us that he even saw some of the peasant children in Kerry enact the marriage of Cupid and Psyche as a part of the May Day pastime.

In addition to the foregoing may be added the following memoranda of the ancient rites and customs peculiar to May Day.

Herbs gathered on May Day are boiled with some hair from the cow's tail, and carefully preserved in a covered vessel. A small portion of this charm is put into the churn before churning, and is also smeared upon the inside of the pails before the milk is "set."

Certain herbs known only to the initiated, but including yarrow, speedwell, and a plant famous for all cattle-charms, which, translated into English, means "the herb of the seven cures," are boiled together, and the water given to cows with calf as a preservation against ill luck and the fairies.

Rods of mountain-ash are placed, at May Eve, in the four corners of the corn-fields, which are also sprinkled with Easter holy water. Balls of tough yellow clay, inclosing three grains of corn, used to be placed by malicious persons in the corners of their neighbours' fields, in order to blight their crops.

A stock of brooms must be laid in before May Day, as it would be unlucky to make any at May time. In case of necessity, a sheaf of straw is used instead of a broom.

In the counties of Kilkenny and Waterford, it was customary for the neighbours to go from house to house, light their pipes at the morning's fire, smoke a blast, and pass out, extinguishing them as they crossed the threshold.[22]

We learn that, about seventy years ago, it was customary for the people in the same locality to assemble from different baronies and parishes, in order to try their strength and agility in kicking towards their respective houses a sort of monster foot-ball, prepared with thread or wool, and several feet in circumference. To whichever side it was carried the luck of the other was believed to be transferred.

In seeking for the snail or slug alluded to at page 53, its colour is taken into account, the white being considered the most fortunate; but the hue of the little animal is said to indicate the lover's complexion.

The long dance, referred to at page 52, was in times past performed with great spirit in the county Kilkenny, at the celebrated moat of Tibberoughny, near Piltown. The assemblage—consisting of the bearers of the May bush, the dancers, musicians, and spectators—entered the moat at the southwestern gap, circumambulated the outer entrenchment several times, ascended the lofty mound by the north-east path, placed the emblem of summer on the summit, and commenced the revels. The May bush, or May pole, was here adorned with those golden balls provided by the beauties married in the neighbourhood at the preceding Shrovetide, as related by Sir John Peirs, and referred to at page 67 of this work. A renowned fairy man, with a large key in his hand, led the van, and having apportioned his prescribed rounds, entered the moat, and then, taking off his hat, called in a loud sonorous voice three times, "Brien O'Shea—he—hi—ho!" Not receiving an answer, he tried another gap or door of the enchanted fort; but his second and third efforts having likewise proved unsuccessful, he, falling back upon the subterfuge of more modern conjurers and Mesmerists, said it was the wrong key he had, or that there was some mistake about the day—it was not the "raal right ould May Day." The great summer bonfire was afterwards lighted in the centre of this fort or rath.

The Glas Gaivlen, the sacred or fairy milk-white cow with the green spots, so famed in Irish story, and from which so many localities derive their names and legends, was generally seen on May Day, and fortunate was the farmer among whose flocks she then appeared. We intend to take up the subject of this celebrated animal at another time, and would therefore be glad to receive local information thereon.

Some of the first milking is always poured on the ground as an offering to the good people on May Day. It is also considered very dangerous to sleep in the open air on May Day, or any time during the month of May. Several of the diseases to which the Irish peasantry are liable are attributed to "sleeping out."

For further particulars respecting the celebration of May, Brady's "Clavis Calendaria" may be consulted.

Should any of our readers observe other rites or customs, or be acquainted with any circumstances or superstitions in addition to those which we have thrown together in the foregoing details, we entreat their corrections and amendments.

END OF CHAPTER II.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Contents | Next Chapter »

NOTES

[20] "Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland," part iii., p. 92.

[21] The Motty's Stone.—"It is said that this huge mass (which one is perplexed to know how it came to occupy its place except during the Deluge) descends every May morning to perform an ablution at the 'Meeting of the Waters,' and then pays its respects to a smaller stone, beneath a tree beside the stream. There is a peculiar virtue, or healing power, in the river at that time; for any persons who are so fortunate as to observe the descent of the stately gentleman, and subsequently plunge with him into the waters, will infallibly be cured of whatever disease afflicts them."—Alric De Lisle; a Poem, with Notes. By Rev. J. G. Angley. Dublin: 1842. Page 17.

[22] For these, and many other ancient rites and legends, we are indebted to an intelligent friend.