The O’Curry Family

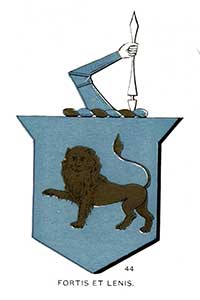

(Crest No. 44. Plate 16.)

THE O’Curry family is descended from Milesius, King of Spain, through the line of Heber, third son of that monarch. The founder of the family was Cormac, King of Munster, A. D. 483. The O’Currys belonged to the Eoganacht tribe, so called from its founder, Owen More, son of Olliol Ollum, King of Munster, A. D. 177. The ancient name was Curadh, meaning “Knight.”

The chiefs of the O’Currys were styled Lords of Carbery, and their possessions were located in the present Counties of Cork and Westmeath.

The O’Currys of Cork were Lords of Ciarraidhe Cuire, now the barony of Kerrycurrehy, in that county.

The O’Currys of Meath were chiefs of Hy-Mac-Uais, or Moygoish, in Westmeath.

Another branch of the O’Currys are given in the map of Ortelius as a clan in Cavan, in the barony of Tullygarvey. They were located about the place afterward called Cootehill. Of this family was John Curry, M. D., the celebrated writer on the civil wars of Ireland.

The most eminent of the name in modern times was the late Eugene O’Curry, the Irish antiquary. He was a brother-in-law of Dr. John O’Donovan, equally learned in the same field of research. His “Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History,” “Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish,” and other works, are among the most valuable contributions ever made to a nation’s history. He devoted his entire life to the work of bringing to light the unknown and long-forgotten records of ancient Ireland, and in illustrating the early civilization and the advancement made in learning, science and art by the Irish people at a time when most modern races were buried in obscurity and barbarism. With patient toil, and no hope of recompense other than the satisfaction of serving his race and vindicating the truth, this great Irish scholar gathered up the scattered fragments of Ireland’s records, collated, elucidated and preserved them for the future generations of his countrymen. Truly has it been written of him:

“In history’s page to write a name—

To win the laurels or the bays—

For power, for wealth, for rank or fame,

Will mortals strive a hundred ways.

“But who will labor all alone

Till youth’s and manhood’s bloom are o’er,

Uncheered, unpaid, unprized, unknown,

A student of forgotten lore?

“See life’s high prizes lightly won

By little worth—yet not repine,

Hear vain pretenses brawling run,

And never make an angry sign?

“But still retrace with patient hand

The blotted record of the past,

Content to think the dear old land

Will know her servant true at last?

“Good men of all the ranks and creeds

Met, planned, and toiled with zeal sublime

To disentomb the thoughts, the deeds,

The glories of the ancient time.

“Old relics of the native art

They loving sought and treasured well;

The sword, the axe, the spear, the dart,

And cross and shrine, and bead and bell.

“The ring, the brooch, the collar bright,

Had all their use and beauties told,

Till flashed again on human sight

The blaze of Ireland’s age of gold.

“But oh, the books—the dear old tomes,

The treasures best beloved of all,

Long hid from harm in native homes,

Deep sunk in flooring, roof or wall!

“Hid from the fierce invader’s ire,

Snatched from the ruffian soldier’s hand,

Saved from the whirl of blood and fire

While foreign robbers swept the land.

“Oh, precious volumes, brown with age!

What joy was theirs—the good and wise—

Who gloated o’er each tattered page,

With beating hearts, with glistening eyes!

“But he of all was chief and head,

The order’s great high priest was he;

They treasured up the words he said

As dogma or as prophecy.

“The time, the tale of harp and sword,

Of bronze and gold, of wood and stone,

The worth of every written word,

The where and when, to him were known.

“Quaint phrases of the olden tongue,

Old scrolls to others bleared and dim,

All Brehons wrote or Fileas sung

Gave up their meanings true to him.

“He for his county’s honor bold,

Smote error, ignorance, and guile,

And shattered libels new and old

That basely wronged his native isle!”

McGee thus describes O’Curry at work: “In the recess of a distant window there was a half-bald head bent busily over a desk, the living master-key to all this voiceless learning. It was impossible not to be struck at the first glance at the long, oval, well-spanned cranium, as it glistened in the streaming sunlight. And when the absorbed scholar lifted up his face, massive as became such a capital, but lighted with every kindly inspiration, it was quite impossible not to feel sympathetically drawn toward the man. There, as we often saw him in the flesh, we still see him in fancy. Behind that desk, equipped with inkstands, acids and microscope, and covered with half-legible vellum folios, rose cheerfully and buoyantly to instruct the ignorant, to correct the prejudiced, or to bear with the petulant visitor, the first of living Celtic scholars and paleographers.” O’Curry died in 1862, aged sixty-six years.