The Peasants of Ireland

THE peasants of Ireland are all sure that they are descended from chiefs. Like the child who asked in a cemetery, "Where are all the bad people buried?" one is forced to enquire, Where are the descendants of the original clansmen? There is no reason to conclude that only the ruling stocks survived. But that belief is so universal among them that it affords the chief clue to their character. You will not understand them unless you think of them as if it was true. No matter how poor their remembered forefathers have been, all are convinced that at some time their families governed. Their pride is not based on the notion that all men are born equal; on the contrary, no one attaches more importance to gentle descent. In their obedient toil it is their consolation to hold that in the past their families were able to profit by the obedience of others. This belief has the same effect when it is justified (as beyond doubt it sometimes is), and when it is not. It explains in part why the peasants of Ireland have so little in common with those of other countries.

An old-fashioned courtesy seems to me their especial characteristic. Take shelter in any hut on the mountains, and you will be greeted as if its inmates had been longing to see you. This will not be due to the fact that you seem prosperous; indeed, you would be even more graciously welcomed if you were in rags. Nor is their courtesy only exhibited when they are hosts. Once, when I was exploring the Burren of Clare, a ragged old woman seated by the wayside accosted my equally ragged driver. "Excuse me, sir," she said, "but did you happen to meet a loaf on the road?" " 'Deed, then, ma'am," said he, bowing respectfully, "and I'm sorry I did not." "Who was she?" I asked him, when we had driven out of her hearing. " 'Deed, then, and I don't know," said he; " 'tis some poor soul that has lost her loaf and will be goin' to bed hungry to-night." On another occasion, an aged man, clad in knee-breeches and a swallow-tail coat, addressed me, as I was climbing a path in Connemara. "I am thinkin', sir," said he, "that you are Mr John Blake." "Well, sir," said I, "you are thinking wrong." "Well, sir," he answered solemnly, "says I to myself as I saw you come up the side, that is Mr John Blake; and if 'tis not, says I to myself, 'tis a fine upsthandin' young man he is whoever he is." Now I am convinced that he knew that I was a stranger; but was not that a charming way to suggest that I should sit beside him on the low ferny wall and discuss the ways of the world?

The essence of courtesy is sympathy, expressed or implied. The Irish peasant has a wonderful sympathy even for inanimate things. One of the poetic riddles in which they delight has been translated thus—

"From house to house it goes,

A wanderer small and slight,

And whether it rains or snows,

It sleeps outside in the night."

The answer to that is a footpath. Hear one of them talk of his domesticated pig, and you will observe a similar fellow-feeling. "The pig, the craythur," will never be mentioned without a hint of affectionate pity. This is one of the reasons why those instructed and respectable animals are not excluded from the warmth of the fire. They and the poultry are as welcome companions as cats and dogs are in England. Since they often constitute the whole wealth of their proud owners, it is the more natural that they should be kept in sight and protected with a constant attention.

A foreigner, seeing a cabin built of mud or of roughly piled stones, and noting that there is a hole in the thatch instead of a chimney, and miniature windows or none, and a floor of clay, and an atmosphere pungent with the smoke of the turf on the hearth, can easily think that there is no comfort to be found in that shed. If, when his eyes are accustomed to the smoke and the dimness, he observes ragged children sharing that refuge with poultry and a litter of pigs, he will be sorry for them. The author of the "Letters to Dr Watkinson" saw such things in the year 1776, and reflected, "It is no wonder that it should be part of the Irish character that they are careless of their lives, when they have so little worth living for. The only solace these miserable mortals have is in matrimony, and accordingly they all marry young." In this he made such a mistake as any foreigner might.

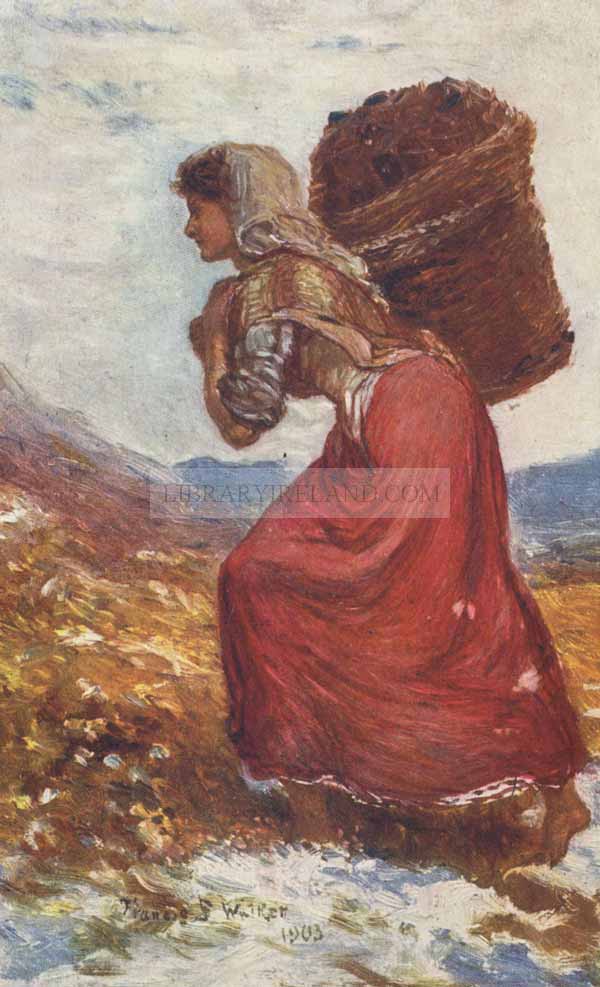

CARRYING TURF

TWO baskets of turf a day keep the fire going, and they are carried daily in many places from the bog to the house by some of the family—often the women.

On one occasion, while resting on a hillside, exhausted by the ascent, I asked a girl with a basket if she did not feel tired with carrying such loads. She said she did not, and if I got into the basket she would carry me up—an invitation I declined.

Many things led to the custom of marrying young; for instance, the traditional notions handed down from the earliest days, and the hot blood, and the mercenary views of the men. Those marriages were fatally provident: every wife had a portion, and this was desired even though it was only a pig; every child was considered an insurance against the perils of sickness and age, since he who had transmitted his strength could look for support when he was feeble. But the chief cause of these unions was the fact that the peasants were happy. The young couples started life with a blind hopefulness and a fatal content. Even to-day, if you do more than peer into the shed from the threshold, if you rest under the thatched roof, you may discover that the children are as happy as kings, and that their father is very proud of his home.

As for the want of chimneys and windows, this has been ascribed to an attempt to avoid certain taxes; but that explanation overlooks the eloquent fact that these homes are of a primitive type. Take, for instance, the remains of the stunted primeval buildings at Grimspound,—these indicate that the first builders of permanent houses adopted this fashion. No doubt the poorer Irish, as soon as they ceased trusting to shelters made of wattles, provided themselves with such homes as now belong to their children. If you bear in mind that the cabins were merely shelters from the storms and the dark, and that the doors were not meant to be shut in the day-time, and would therefore be useful as windows, you may perceive why folk who detested all changes and were not very fond of superfluous labour, remained faithful to the ways of their fathers, and more than pleased with those rudimentary familiar abodes; you may understand how the savour of the smoke of the turf became so dear to them that even after a long absence a whiff of it is enough to make exiles heartsick for Ireland.

There were a great many happy lives led in such homes in the old days. Even Dr Campbell caught a glimpse of another solace besides matrimony, when he witnessed a dance. " Of what extremes is this country composed!" he wrote. " Here everything wore the face of fertility and pleasure. I had heard of vivacity before, and had seen it in individuals; but never till now had I seen it universally pervade so large a mass. The women vied with the men in the display of animal power. You would have said they breathed fire. These people have quick and violent spirits, betraying them sometimes into sudden starts of indecorum. I have seen the whole room in a convulsion of laughter at a false step made by one of the dancers. How different," he continued, "are the effects of the same sensibility in another line! I had been strolling through the market, when I saw a poor woman who had lost her purse, containing but two or three shillings. The poor creature wept aloud, and the women about her joined in the lamentation, which had such an effect that a general outcry was the consequence, so piteous and so doleful that the men themselves could not refrain the sympathetic tear." If he had dwelt on these changes of mood, he might have appreciated the singular buoyancy of the peasants.

In those days, they had all the joys of their masters. Since they were not allowed to have pistols or swords, they fought their duels with stumps of hawthorn or oak, simple weapons but sufficiently murderous. The hero who pranced through a fair, brandishing his cudgel, and shouting, "Who'll tread upon the tail of my coat?" resembled Jack Taafe riding his tailless horse. Each was pining to taste the joy of battle. In this, the peasants outstripped the gentlemen; for they improved upon the custom of duelling by indulging in Faction Fights, in which destructive encounters gangs of men smashed one another with cudgels or lopped one another with scythes, joyfully, without any ill-will. These gangs represented rival parishes or villages or families sometimes; but that was only a detail. In Kerry, for instance, all men named FitzGerald fought all Moriartys, at least twice a year, to commemorate the legend that long ago a Moriarty betrayed an Earl of Desmond. But when a FitzGerald rushed forth shouting, "Who'll show me the face of a tremblin' Moriarty?" he was not thinking of the past; he merely wanted to fight. So, too, the peasants had the revelling; and though this was perforce less costly than that of their masters, they developed it by feasting at funerals, and by holding the Wakes when they assembled to grieve by a dead neighbour's coffin, and remained to carouse. And they had the hospitality, which also was greater because they had so little to give. Like their masters, they welcomed all to their homes, because they were intent on the pleasure of giving and on the giving of pleasure.

In all this they were, as Dr Campbell observed, "careless of their lives," and of everything else, as the landlords were also; but that was not caused by despair. His mistake was natural, and the horror he felt when he saw their condition was shared by many other travellers; for instance, by Young and by Newenham, and Wakefield and Gough. The life they saw was not in accordance with their notions of comfort; and it is hard for the rich to understand how much happiness belongs to the poor. Besides, they were misled by the mournful look of the peasants. While these had the same joys as their masters, they had the same melancholy at the root of them all, and theirs was more visible.

A HAPPY HOME

ON taking refuge here from a storm, which continued nearly all day, I was hospitably entertained, and when I left, neither the good man nor his wife would take any remuneration whatever. As a small return, I have endeavoured to give their likenesses in the happy little homestead as I saw it.

If you see wandering Arabs, the only people equally poor with whom they have much in common, you will be struck by their obvious gloom; but if you grow intimate with them, you will find that it is the chief of their pleasures. Just as the Arab's proud sorrowfulness is quite unconcerned with his complete destitution, so, while these peasants were mournful, it was not because they could see anything amiss with the cabins for which they were eager to pay, or to owe, an exorbitant rent; it was not because they were quite certain that they would always be penniless.

In all this they were akin to the gentlemen, but without imitation. Why should they imitate men whom they regarded as their equals at best? It has been commonly thought that they have a great respect for the "old stocks," the families long ruling among them; but this is one of many delusions. Their attitude has been better explained in a modern novel, in which one of the characters says, "They show respect for the old sthock, when they think it annoys a new one, or if they are wantin' to soother you. An' all the time they are laughin' up the sleeves of their waistcoats, and thinkin' a fine old sthock of a weed it is; and this lad came over wid Cromwell hardly a thousand years ago yet, an' he looks down upon one that was King of all the counthry before the mountains were made." Remember each man was convinced that if he had his rights he would be a ruler himself. When respect was really given, as it often was, it had been earned by the same qualities as would have procured it for the most penniless; when their rich neighbours were loved, as many were, it was not because they were masters, but because they were loving. Among themselves the peasants have always discussed those other gentlemen, the landlords, as if they were judging their equals, or their inferiors when a ruling stock happened to be English; and in such talk they have not given them their usual titles, but familiar and descriptive ones, such as John of the Blankets, or Francis of the Wine, or James of the Girls.

Often when a peasant betakes himself to bed he will cover the smouldering ashes on his hearth instead of extinguishing them, so that they will suffice to make his fire glow in the morning. Take that as a parable. To understand Irish History, you must remember the survival of fires smouldering hidden. When people are astonished to find that nowadays the peasant exhibits so little of the former apparent veneration, they forget, or are unaware, that this was never more than external. When you deal with an Irishman, it is well to remember that he will never forget, and that it is improbable that he will ever forgive. Indeed, if I may use an Irish locution, we are apt to remember things that never happened. Half of the bitterness and bigotry on both sides in Ireland is caused by the memory (that is the belief in the occurrence) of massacres and other atrocities that were never committed.

This reminds me that my country has long been renowned for "bulls," and these call for a word of explanation. The Irish bull is in many cases intentional: in some it is caused by the fact that the speaker is using a language foreign to him, but in more it is only a quicker and more vivid way of expressing his thought. Take that famous example, Sir Boyle Roche's saying, "No man can be in two places at once, like a bird." To my mind it suggests a bird's quickness of flight admirably. Roche was excusing the Sergeant-at-Arms' failure to seize a man who was at the opposite door of the House of Commons. He was a professional jester; and I have not the least doubt that he could have expressed himself with a deliberate accuracy, if he had chosen. Or take the case of the man who, to express his bewilderment, said, "As soon as I knew where I was, I found I was somewhere else"; or of that other who remarked that "he was never at peace except when he was fighting." In both of these the confusion of thought is only apparent. There are, of course, many idiotic bulls; but these have been made out of sheer amiability, in a desperate attempt to amuse. You will hear them on the lips of the boatmen of Killarney and the car-drivers at Dublin and Queenstown.

"The people of our island," said Curran, "are by nature penetrating, sagacious, artful, and comic." Very often, an Irishman is only comic because he is sagacious. There is plenty of wit; but very little humour. The peasants have always been famous for their quickness of tongue. The other day an English traveller said to his driver, "Why do you speak to your horse in English while you talk Irish to your friends on the road?" "Sure," said the driver, "an' isn't the English good enough for him?" Here was a good instance of an Irish reply; and local traditions preserve many epigrams; such as the one by which a wandering poet avenged himself when he had been slighted by a landlord named Trench. Thus he wrote—

"You will find grace in the pulpit, and wit on the bench;

But 'tis nothing but dirt you will find in a trench."

Indeed, the peasants differed mainly from the landlords in being much more clever and very much more studious. This, I fancy, was due to the fact that they were more Celtic. Their passionate veneration for learning and their zeal in acquiring it, was shown in the old days by the respect they all paid to the Poor Scholars, and by those strange Hedge Schools in which ragged schoolmasters expounded the beauties of Ovid and Virgil to students in rags. Note that the Poor Scholars, who wandered over the country, seeking instruction and publicly debating with others and finding gratuitous welcome wherever they went, followed a custom that was practised in mediaeval Europe. For many a day Ireland has been (for good and for evil) behind the times.

In the Middle Ages, men helped one another in guilds; they were cruel because they were childlike and accustomed to violence; they were religious. In the same way, the Irish peasants have always been prone to form Secret Societies for mutual help; they have often shown cruelty for the same reasons, and for the further one that, setting scant value on their own lives, they were the less reluctant to kill others; their faith has been always profound. Even nowadays they still keep a mediaeval simplicity.

Simplicity and kindness and courtesy are their most obvious merits. That was why a German traveller said to me once, "The Irish, when they are bad, they are the worst; but when they are good, oh! I love them; they are so soft." Still, even when they are good, they are not always quite as simple as they seem when they think that you will be pleased by their blunders or when they are being cross-examined in Court.

This reminds me that they have often been blamed for ignoring the Laws. But you should remember that those Laws are not theirs. In the days of Henry VII., Finglas reported, "The laws and statutes made by the Irish on their hills they keep firm and staple, without breaking them for any favour or reward." So too, Sir John Davies, under James I., said, "There is no nation under the sun that love equal and indifferent justice better than the Irish, or will rest better satisfied with the execution thereof, although it be against themselves." And Coke, in his Institutes, corroborated this, adding, "which virtue must of necessity be accompanied by many others." But they have never been able to see that their conquerors dealt equal and indifferent justice, or had any right to command them.

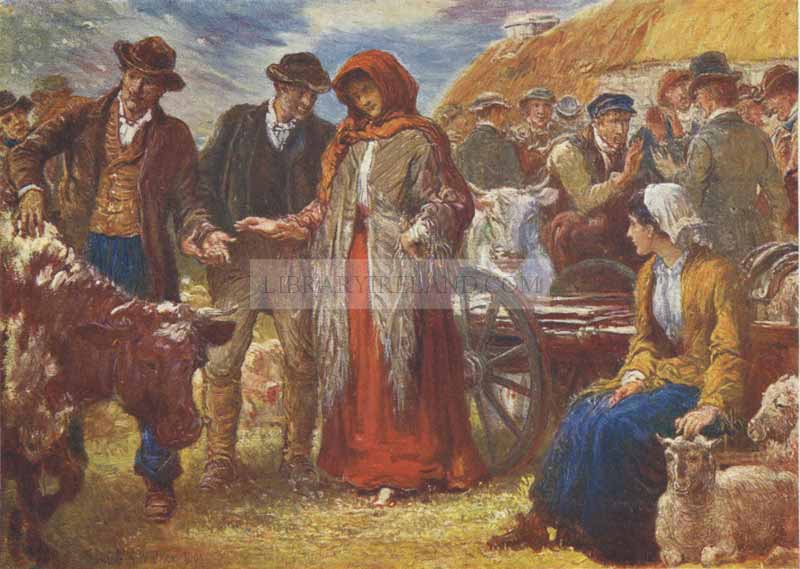

A FAIR

GENEROUS in their hospitality the Irish undoubtedly are, but when they buy or sell, none are more keen to their own advantage. A fair gives the stranger a considerable insight into these business qualities, for he may watch the natives higgling for hours over a few shillings. The custom is for those who agree to the terms of the others, to slap them on the open hand in token of agreement. When both parties are obstinate, a friendly neighbour sometimes places their hands together with his best advice.

Now, if you keep these things in mind, you should understand why their recent attitude has differed so greatly from their former subservience. Some have ascribed their desires to the fact that in the primitive days each clan held its estates in common; but this is far-fetched: I doubt whether many of them had heard of that doctrine, nor have they the least wish to restore that state of affairs. It is true that there is in the Irish mind an essential Socialism on which is founded the extreme hospitality; but it does not apply to the land, for every man wishes to be the owner of some of it. Remember that there was an immemorial hostility, smouldering hidden, a resentment based on a belief in spoliation; and that this was exasperated by the increasing faults of the landlords, for every year of reckless life found these more embarrassed and therefore more apt to be Absentees, and less able to help their tenants or to refrain from demanding high rents. Remember, too, that the peasants are still in many ways mediaeval, and that English Laws and the contracts enforced by them are not in the least respected. Remember that they believe that if they bad their rights they would be landlords.

But why did they never assume this attitude before? Well, they had no political power; they were not blessed with the leaders they have found in our days; and, above all, they were greatly inclined to be content. That must have been hard in many cases; but it is wonderful what a man can endure when he is happy. Then came the Famine, and it broke Ireland's heart. Such hopefulness as remained to them turned to another country; and the strongest and the best of them left Ireland for ever. Meanwhile, those who clung to the forlorn cabins were ripe for a mutinous despair.

There had been mutiny among them before, not without reason; but whenever the Catholic peasants had risen in arms since the times of the Tudors they had been fighting for their Church. The chiefs for whom their fathers had fought were all broken, and the Irish had never been a united and independent nation, so these rebels were intent on regaining religious liberty. That was a thing they had lost; but national freedom and identity had never been theirs. This explains the perplexing history of Ireland's attitude during the Great Civil War. When the Irish under Owen Roe fought for King Charles, it was not out of loyalty. The Irish peasant has never seen that he owes the least loyalty to any English monarch. When Owen Roe changed sides and made terms with the Puritans, it was because he was convinced then that by so doing he was more likely to gain tolerance for his Faith. Again, in Ninety-eight, though the Presbyterian rebels of Antrim, most of whom were of Scottish or English descent, fought to establish a Republic, the Catholic ones took arms for their Creed. It was all very well for the eloquent leaders in Dublin to mimic the French Revolution: the men who died on the Wexford moors were not thinking of that. The Rising of Ninety-eight failed because the Catholic rebels made their part in it a war of religion. That broke the Presbyterian attempt to participate, and dealt a deathblow to the Society of the United Irishmen, which (founded mainly by Protestants) had from the first aimed at uniting the two Creeds in rebellion.

The attitude we have seen in our times is different. If the peasants are still as religious as their fathers were, certainly it is in a different way. They have changed in many ways since the Famine. In the old days, the inner elation of piety set them above outer discomforts. Formerly they clung to their homes; now they flock to America. The emigration is caused in part by their hopefulness; they see a land of fabulous gold in the shine of the sunset. It is recorded that when Dick Whittington set out, he heard the bells calling, "Turn again, Whittington! thrice Lord Mayor of London"; but when Mike Flanagan leaves his home, sad at heart, he hears them advising, "Go on, Flanagan! Go on, Flanagan! Boss of New York." And those who have not been enticed by such an ambition, those to whom Tammany Hall is still unknown, dream of the incredible wages of which they have heard.

When the emigration began, it was compulsory. The first who went to America had little more choice in the matter than had the Irish whom Cromwell shipped to Barbados; the land was wanted for cattle or for new towns, as in Antrim, and the men who had tilled it were no longer required. In 1776 a traveller wrote, "The landlord who gets his rent without trouble, and the grazier who thrives upon depopulation, prefer cattle to peasants"; and to this he ascribed the vacant look of the fields. After his time, the emigration increased, and it was not retarded by the fact that America was hostile to England; but it only became a national danger when the Famine of 1847 awoke the poor from their dreams. There had been famines before,—indeed, in the barren wilds of the West, hunger was constant, and year after year men died of it; but the one of that winter surpassed them all by so much that they are forgotten, while its remembrance is never put out of mind. To this day it is called "the Hunger." It is not often that any will speak of it. You will hear a man say, "This is a lone part of the counthry now; but yondher road did use to be black with people comin' into the town, before the Hunger"—but I have never met any peasant who would talk of that time. Which is a proof that the thought of it is deep in their hearts, for they speak a great deal about external affairs and not at all about the things that mean most to them. The remembrance of the Hunger now governs the whole of their lives.

They had feared nothing before; certainly not death, for apart from the piety by which that was made welcome, they had the Celt's readiness to die; but they had not the courage to face such a winter again; and since it appeared to have come on them without any warning, for all signs of that peril had been unheeded by them, they had done with security. Fear banished the emigrants who fled in that time, and though the thousands who follow them still have hopes to delude them, they have inherited that unreasoning terror. Watch any emigrant ship leaving the shore, and you will see very few confident faces; in most you will read not only the natural reluctance of exiles, but also a dread of the alien land to which they are bound and of the menaced life they relinquish.

Some have been surprised by discovering that the emigration has by no means decreased in the last couple of years. This is a time of hope, we are told. Has not England done wonders for Ireland? Beyond doubt it has, for without discussing the wisdom of the Land Act of 1903, we can agree that it was a wonderful remedy. Then why should the people fly from the shore when they are about to be given what they are supposed to have wanted? Have they not heard how Parliament is nobly investing an enormous amount of the Ratepayers' money in a bold speculation? Have they not been assured that the English Garrison has been abolished at last, and by England? It might be alleged that their continued flight proves a disgusting ingratitude. Politicians can debate about that; but, as a disinterested observer, I may suggest an explanation to them.

Not long ago, an old peasant was asked such questions as these, and he replied, "I do be hearin' this; but I am thinkin' it would be a cruel time for the poor." I need not say that he was an illiterate and irrational man. In his confused mind there was a lingering notion that the landlords had not been altogether a curse; somehow it seemed to him that he remembered many kind deeds, much generous help given by men who were not overburdened with money, and he did not appear quite certain that this aid would be found when many small farmers had divided the fields. He was not going to emigrate—he was too old, and there was nobody waiting to give him a home on the other side of the Ocean;—but it was obvious that this amazing intervention of Parliament would not have detained him. Apparently, he thought that the farmers in his part of the country had no very great kindness for the labouring men. There is this to be said for his view,—a resident landlord (and there were more of these than you might imagine) would, if he was not quite inhuman, have a tendency to be fond of his own people because they were his, because their fathers had lived side by side with his for many a year; and it would be probable that the ladies of the Big House would be accustomed to show kindness to the neighbouring poor. The many new owners of the divided estates will not have the same power to help nor the inherited tradition of patronage. It may be better for the labouring men to be taught independence; but they cannot be expected to find pleasure in the lesson. That old peasant's view may be held by many who keep their thoughts to themselves.

As for the farmers, who (instead of continuing to toil in unprofitable fields, while rejoicing in the knowledge that these will, if everything goes well, belong to their grandchildren) obstinately sail to America, there are some excuses for them. There is an Irish phrase meaning "on the brink of the summer." That time of the year, the last day of the treacherous Spring, is perpetual in our country of hope. When will that summer begin? When the birds sing again in the forest of Desmond. We have been so constantly drugged with hope that it can retain no power on us now. You may tell us that fine days are beginning; but alas! we have heard it all so often before. These men believe that an impossible happiness is awaiting them somewhere; but not in poor old Ireland. Say what you like; and they go sadly and silently, in spite of your arguments.

STEEPLECHASING

IRELAND holds annually the most important horse show in Europe, and steeplechasing may be said to be its national sport. This sketch was made at Claremorris, Co. Mayo.

The Irish peasant is by nature a stationary man. He is a fireside traveller: in his dreams he will wander over the hills and far away. If you can describe far countries to him, he will listen to you with open delight, though it will be probable that he will not believe a single word that you say; but he will not have the least wish to emulate your ridiculous vagrance. You will find a great many who have never gone more than a few miles from the cabins in which they were born, many who would feel utterly lost in a neighbouring parish. For this reason, the Mayo tinkers, who ply a wandering trade, are distrusted because their life is unnatural; and indeed it is more than suspected that they are under a curse. This natural abhorrence of travel is one of the reasons why the Irish continue to emigrate. The thought of so great a voyage was so dreadful to them, it involved such a wrench, that when once they had grown accustomed to it, accepting it as part of their destined sorrows, they could not unlearn that hard lesson. The Hunger taught them, once and for all, that they must go out from the dear and familiar places.

Besides, though they loved their homes still, it was not with the old happy affection. The hills that had witnessed the long agony of that winter had changed. The weather and the soil of their homes had been the instruments of that wholesale destruction; and from that time the love was mingled with fear. The dark valley in which he abides may be dear to the peasant; but there are hours when it is ghastly to him; the mist on the mountains will remind him of the blight on the fields; and even if he lingers, because he lacks the money required, he is quite sure that it is madness to stay.

What would have happened if the potato had never been brought into Ireland? Perhaps one may conclude that the peasants of every part of the country would, in that case, have shown more of the virtues now peculiar to those of Donegal. In those Highlands, it is not easy to cultivate even the potato, and therefore the people must derive their subsistence from the sea or from indoor work. This is true also of Connemara; but there the people dreaded the sea, and were so quelled by misfortunes and by their climate that they were never industrious; and they were so much concerned with the Other World that they regarded the trivial affairs of this one with apathy. The potato was easily grown, and would thrive in soil that would bear no other crop; it would survive rains that would be fatal to corn, and it would furnish a food on which an Irishman would be able to keep body and soul together. The Celt is abstemious. Julius Solinus reported of the Irish, that "they hold them appeased with fruit instead of meat, and with milk instead of drink." Who ever saw a fat Irish labourer? Their wives may look cosy enough, though that is exceptional; but the men will be lean. To this day you will find that they attach very small importance to food. This was one of the points in which they differed from their masters; for in the old days the gentlemen loved a table that groaned beneath a good load of bottles and joints: it was, I believe, a landlord who said "a turkey is an inconvenient bird; it is too much for one, and not enough for two." For these reasons the potato became the staple food of the peasant. It was only too well adapted to suit the facile content which is so easily mistaken for laziness. This food left them weak, and therefore inactive, while it enabled them to keep alive without steady toil: it softened their character, and it may even be that much of their piety was due to their diet.

In the time of the Hunger they at last learnt in what peril they had lived for so long. The one food lost its savour, and there was a new darkness in the mountains for them. The roots of their stock were frozen; and since that time it has been like a tree that has no hold on the ground. Even if the remembrance of the Hunger has grown less vivid (and that is open to doubt, for this is a people that lives much in the past), its effects have increased. The children are now born with the instinct to fly from the land. In this, as in other things, the Celt is reverting to his primitive ways: he is once more afoot in the long pilgrimage westward. Year after year, the land of their birth has less attraction for them; for as it becomes more depopulated year after year, it grows sadder and quieter. The Dances have lost their vigour, the Wakes have no joy in them, and the glad war-cries of the Factions are heard no more at the fairs. The solitude has become overpowering.

Yet those who remain have still much in common with the peasants of a happier time. They are still pleasure-loving; and for that reason they are the more inclined to depart. They still cling to one another; and for that reason their hearts turn to America, where most of their race have found homes. They are more peaceful than ever, and they are contented still, after their fashion. The most obstinate man that ever resisted eviction was proving his content, for he only demanded to be left to himself. Examine some of the farms from which men have been evicted with necessary violence, and you will see that only a very contented man would have thought it worth while to struggle for them.

As for the remnant of the landlords of Ireland, they show less of the nature for which their fathers were famous in the merry old times. That is natural, since so many of them have been educated in England and since the fashions have altered. When their fathers duelled and feasted, Englishmen were doing the same, though not with such a noble extravagance of money and life. Also, their fathers had more money to spend. But the changes are all on the surface; the old nature is there, though it is hidden from sight. Sometimes there are glimpses of it; indeed, one might name several men who seem out of place in these prosaical times, and look as if they ought to be wearing snowy wigs and bright silken clothes and a neat little sword. It is probable that if duelling had not been abandoned, there would have been very much less political eloquence. Even in recent times, there have been examples of men who persisted in treading in the steps of their ancestors, such as Carden of Barnane in Tipperary (Woodcock Carden he was named by his admiring tenants, because they could never succeed in shooting him); he was a man as whimsical and brave and outrageous as ever was seen in the days of wigs and snuff.

In one thing the landlords have changed places with their tenants of late. There was a time when the worst grievance of the latter was this,—they had very short leases, or were tenants at will, so they were never secure. Now for several years the landlords have been owners at will. At least, the new Land Act, whatever else it will do, will put them out of their pain. Insecurity was always the curse of Ireland; at no time in its history have either the rich or the poor in that country been safe; and this is one of the facts that did most to control the nature of Irishmen. The Land Act of 1903, whether it was a rational intervention or not, may remedy this for a time; and since it bids fair to eradicate the men of whose faults so much has been heard, while very little has been said of their merits, we may hope that the country will once more become the Island of Saints.