The Island of Ruins

COUNTRIES have their fates. England suggests a summer noon, Ireland an autumn morning. One has a comfortable look, as if any disaster could be but an unusual cloud; the other seems moulded for sorrow. One is crowded and prosperous; the other is lonely and fallen. You might think that Ireland's condition was the work of a conqueror who made a solitude and called it Peace, and this theory would be supported by the number of ruins, for in every part you see the wrecks of old castles and churches and abbeys, and—a sight more pathetic—the desolated homes of the poor; but this is a deceptive appearance, for if you enquire into the history of those remnants you learn that many of them were made by the Irish, and that others were merely left to decay. Irish landscapes are often made to look more unfortunate by the bare walls of roofless cabins among the hedges or alone on the hills; for each will tell you of hearths now cold and of families vanished. There is truth enough in that, for many of them were tenanted once by people who afterwards emigrated; but when English rustics have gone they have not left such sad tokens. The wrecked survival of these cabins was caused by Irish ways. The Irish peasant preferred to build a shed for himself rather than use one in which some other family suffered, and he did not wish to be haunted by its former inhabitants or its ancient ill-luck. Because the cabins were rudimentary, they were built at small cost; and there was no need to pull down the old ones, since the fields were abundantly provided with stones. Also, he knew that it was unlucky to take stones from the dead. This belief guarded the ivied hulks of the castles too, while those of ecclesiastical buildings were further protected by veneration. In addition to this the peasant saw that if the walls were kept standing they would be useful as shelters for cattle or for men caught in storms. For which reasons he left them alone, not feeling that they were unsightly or out of place. Nor are they, for the weather of Ireland tinted them soon, and they seem only too natural; they endow that silent country with much of its mournful attraction.

Was Ireland ever without their suggestion of calamity? It is obvious that many are recent, and that others were made by Cromwell or Sidney (Big Henry of the Beer, as the Irish called him) or their partners in the gradual conquest, while most of the abbeys were wrecked after England was Reformed. From this we can conclude that their number has been greatly increased since the English improvements began. But since that time the most conspicuous of them have been permanent. In the merry old days of the eighteenth century they stood like skeletons at a feast. Then, as now, they were eloquent of Irish ill-luck and Irish resignation. Swift wrote of "the general devastation in most parts of the Kingdom, the old seats of the nobility and gentry all in ruins," and the contemporary or later explorers agreed with him. There can be no doubt that even the inhabited houses then appeared in most cases neglected and ruinous in comparison with English abodes, and that the look of decay was increased by the solitary remnants around them. As for the times before the conquest became effectual, you have only to read the Annals of the Four Masters or any other old record; on every page of them you will learn how kings and chiefs and knights harried their neighbours, burning their holds. So it is safe to decide that ever since building began Ireland has always been stocked with prominent ruins.

This is natural, since it has always been divided and always an Island of Soldiers. The courage of its people was vain because they were divided. While less heroical nations conquered others and were enriched by their spoils, this one, apart from the world, ravaged itself. The Irish fought one another because they were penned in this cloistered island and because they were Celts. Unfortunate places were left to unfortunate races. Thus you find the Celts holding the Highlands of Scotland, the Welsh mountains, and the hard moors of Cornwall and Brittany. In those they were separate (does not Wales mean the Country of Strangers?) and therefore unaltered, and they were inspired with the melancholy joy of the sea. In those they found rest when their pilgrimage to the sunset was limited by the Atlantic; and loving them, they became dwellers in a land of illusions and children of the mist and the waves. Some hold that the Arabs and Moors are Celtic in origin also; and it is certain that there are Cromlechs to be found in Algiers, and that Ireland's Annals narrate that its Fomorian stock came from North Africa. Some credit the Spaniards with the same derivation; and there are many arguments in favour of that; for instance, Don Quixote was a typical Irishman. The three books in which you can best study Ireland are Don Quixote, the Imitation of Christ, and Tristram Shandy. But for my part I hold that the only true Celts in these and other stocks are the unfortunate peoples, such as the Basques and the wandering Arabs. The Celt was always unlucky and content with ill-luck.

It was a Welsh bard who said of his countrymen, "They always went out to battle, and they were always defeated." This was equally true of the Irish. And their especial pugnacity was, I believe, due to two causes—the survival of primitive ways in this End of the Earth, and the strange peace that brooded over the hills. They lived in the exasperating hush of a cloister. There is a saying still in the West, "It is better to be quarrelsome than lonesome." This was their maxim: they fought and were riotous when the unnatural loneliness and peace of their land were beyond their endurance. In that consecrated seclusion a man had to be either a saint or a soldier, or both.

As far back as their history or mythology goes, their favourite occupation was fighting. This can be learnt not only from their Annals but also from outer evidence. Julius Solinus recorded that when one of their women gave birth to a son she placed the first food in his mouth on the point of his father's sword. Tacitus, while recording their courage, recognised the chief source of their weakness, for he said that Agricola was confident of subduing their country with only one legion, because he counted on obtaining allies after he landed. In after days, Giraldus Cambrensis related that when they christened their sons they left the right arm unbaptized, so that it should be pagan. Spenser wrote, "I have heard some great warriors say that in all the services which they had seen abroad in foreign countries, they never saw a more comely man than an Irishman, nor he that cometh on more bravely to his charge."

BLARNEY CASTLE

THE lovely groves and grounds that surround the castle had more interest for me than the structure itself. However, I thought I must kiss the Blarney stone, and proceeded to the top of the castle, about eighty feet high; I found the stone was about four or five feet down from the top, and that it would be necessary to stoop over, head down, and hold on by bars, or be held by the legs. Seeing me hesitate, a man asked me: "Are you afraid?" "I am." "Well, no man that's afeard ought to go a-kissing. All kissing should be done sudden; when you hesitate it's serious. Make way for that young lady, she's not afraid." The feat accomplished, he cried out, "A cheer for the young English lady." "No," she replied, "Amurrican!"

These are only a few of the witnesses that could be cited to prove that military fame. Unluckily, it was not earned in united attacks. The many miniature nations battled against one another, and did not desist from that even while they were also concerned with the activity of the Danes and the Normans, nor afterwards, for the Old Irish fought among themselves and against the English of Ireland, while both had their wars against the English of England, till in the wavering scales was cast Cromwell's preponderating sword. After that there was one more campaign, when the Catholic Irish took arms for King James, not for his sake (to this day he is known by an opprobrious title), but on behalf of their creed. Then the battles of Aughrim and the Boyne taught the wisdom of quietness. It is still told in the West, how, on the night of the battle of Aughrim, the Tuatha-dé-Danann were seen by many to dance on the raths. They were rejoicing (it is said) because the Milesians, who had conquered them a very long time before, were broken at last. It seems that in this country the dead are no more able to forget than the living.

Since that day Ireland has known peace. This, though it was broken once by a partial rebellion and was formerly enlivened by duels and Faction Fights, became the chief cause of the national sadness. Still, in that deprivation of war there have been comforts; it has been possible to fight about religion and politics, though not in the old glorious way, and men have been able to cling to the belief that their country will see battles again. In Connemara, trust is still put in a prophecy, according to which, the greatest and last battle of the world will be fought there beside the Mountain of Gold.

Meanwhile, those who could not abide that deprivation went "out on their keeping," not on Irish hills as their fathers had done, but on foreign shores. Those soldiers of fortune preserved the military fame of their home. Nor did the emigrants allow it to dwindle. When the United States asserted their freedom, it was with the help of the exiles from the Protestant North; and when they waged their Civil War, Irish Brigades destroyed one another. In our times Ireland provides its former antagonist not only with private soldiers second to none, but also with field-marshals and admirals.

Has all this courage been vain? Many foreign fields were enriched by the squandered blood of the Irish. It is related that when Sarsfield (whose first laurels had been gained when he fought against William of Orange) took his death-wound in battle abroad, an exiled soldier of France, his last words were, "Would God that this blood had been shed for Ireland!" When, in the American Civil War, Cobb's Irish Confederates, holding the woods beside Fredericksburg, saw the men of the Federal Irish Brigade charging up from the river, they recognised them by the green that they wore, and an officer said, "They are Meagher's men! My God! what a pity." In that war the Irish enemies did battle for the States in which they were at home; but the soldiers of fortune wasted their blood for foreign countries and for causes not theira When they fought against England on many fields, they encountered their own countrymen often. From the days of Crécy and Agincourt, Irishmen have never been lacking, and have never been laggards, in the armies of England. Even in Queen Elizabeth's wars there were some, like the Black Earl of Ormonde and his followers, carrying fire and sword through their own land in her service. Even Cromwell had many Irish allies, some of whom, like Lord Inchiquin, surpassed him in ruthlessness. When the Wexford men rose in Ninety-eight, there was an incident that could only have happened in Ireland.

This was during the battle of New Ross. The rebels were triumphing, and as they charged over the long wooden bridge in a wild crowd, all crop-headed, ragged and desperate, armed only with pikes, following a green banner that bore the words "Death or Liberty," they were met by the soldiers, pig-tailed and powdered men, wearing plumed helmets, high stocks and red coats, swinging together rigidly at a word of command, fighting mechanically. At first the soldiers reeled back; but then their leader, General Johnson, plunged forward alone, calling to them, "Irishmen, will you abandon your countryman? My brothers, will you abandon our flag?" And the flag to which he pointed was the English one, glowing red through the smoke of the burning houses and still fluttering over the captured Three Bullet Gate. Then the soldiers followed their countryman against their countrymen, charged with the bayonet, and broke the rebellion in rescuing the flag of their conquerors. Those dissimilar combatants had been reared in like homes, in thatched cabins apart on the moors or assembled in peaceful and disorderly villages. They were not even separated by creeds, for many of the soldiers were Catholics.

To-day you will see the men of the Irish Constabulary, soldiers in everything but the name, and excellent ones, disciplined and martial and fearless, patrolling the quiet roads in the fields or the scarcely more animated streets of the towns. Their boyhood was passed under thatched roofs or in such somnolent towns as they watch; and their manhood is spent in controlling their countrymen. Nor is that task uncongenial, for it might be said that in Ireland the Irish constables and soldiers have chances of harassing their natural enemies. This would account for part of their zeal; but not for the contrast between them and their undisciplined brothers. Why have they changed? Because being Irish they love martial discipline and are faithful to their salt.

Seeing an Irish soldier, dapper and spruce, you might imagine him entirely transformed; but the change is on the surface; and if you are baffled by his moods, you should study his nature where you can find it unmasked, in the home of his childhood. Strip him of his uniform, free him from orders, and set him to till rocks and owe rent for them and be lulled by the moist air and be surrounded by the kind negligent ways, and he will be shiftless again, slouch as his father did, and be as contented a man as ever smoked a black pipe full of wind happily when tobacco was lacking. While he is in the ranks he is governed by his Celtic fidelity and his love of fights for their own sake, regardless of the rights of a quarrel. If duty called him to Ireland, he would gratify an inherited tendency to fight against countrymen. But that tendency must not be mistaken for hatred: our fights are compatible with brotherly love.

When Meagher's Irish Brigade was encamped beside the Potomac, its men began singing an Irish ballad one night around the bivouac fires, and then it was echoed from the darkness in the opposite woods, for their Confederate countrymen lifted the chorus. Those enemies remembered their bond then, just as they did when Meagher's men died in a last mad assault on those impregnable woods. Belfast is the Orange stronghold, and yet the most bigoted Catholic takes pride in it because it is Irish. There is affection in all his hostility; and in the least Orange parts of the South you may hear the doleful and wandering ballad-singers chanting,

"The Lord in His Mercy be good to Belfast

The grief of the exile she soothed as he passed."

Talk with one of those stern constables when he is off duty, and you will find him a patriot. In all our loved battles we remember the bond.

The truth is that in Ireland we have a limited outlook. Just as the clansmen of old followed their chiefs and slaughtered their neighbours joyfully, and as the eighth Earl of Kildare's retainers wrought havoc in Ulster when he was Deputy, and as the Black Earl of Ormonde's men hunted the Crippled Geraldine when the Dark Wood of Desmond was white with snow, and as the O'Briens of Clare sacked Cashel Cathedral when wavering Inchiquin was fighting for Cromwell and obeyed him as gladly when he fought for King Charles; so the Irish and Catholic soldiers charged with Mountjoy and Johnson at New Ross, and to-day Irish and Catholic constables keep order in Ireland. When the Celt is controlled by his fidelity he will render an impartial obedience. This is one of our many mediaeval traits, for in the Middle Ages no man who served was affected by the rights of a quarrel, he was no more than a weapon in the hands of his master. This perpetual limitation has done much to make Irish courage vain. Moreover, that restricted valour has caused most of the country's sufferings, since a less warlike race would have been subjected with ease.

Certain it is that Ireland has always been haunted by a curious ill-luck. When King Brian routed the Danes at Clontarf, he was killed in the hour of victory (so the Annals relate), struck down while he knelt to pray after the battle, and thus his triumph was nullified. When in 1579 Sir James FitzMaurice of Desmond had seized Dun-an-oir, the Fort of Gold, in the Highlands of Kerry, and held it with an army of foreign veterans, and displayed Spain's yellow flag and the Pope's standard above it, thus bringing the Irish rebels the help they had demanded so long, he was struck down in a chance brawl at the Ford of Clonkeen. And still (if one can believe many witnesses) unearthly sounds of battle, the clashing of invisible arms and the shouting of victors and the shrieks of the vanquished are to be heard at night once every year on the field of Clontarf and among the mossy remains of the Fort of Gold. When General St Ruth led the Irish at Aughrim, the first cannon shot killed him. When in 1796 a French fleet of forty-three vessels, carrying two generals, Hoche and Grouchy, and fourteen thousand men, sailed to assist an Irish rebellion, the weather defeated it; for though the English admiral was evaded, only sixteen of the ships reached Bantry Bay, and then they were baffled by such a gale from the land that after a week's buffeting in the surf between the snow-covered mountains of the country they sought, the attempt was abandoned. There have been scores of such chances, and these have resembled the private ill-luck that has haunted the Irish.

It is probable that you have heard that singular phrase, "the English Garrison." This is a humorous method of describing the landlords. You will partly appreciate its felicity when you remember that among them there are the descendants of the Irish princes, still claiming the old titles; for instance, the O'Conor Don, the MacDermot, and the O'Donoghue, and others who bear English ones—for instance, Lucius O'Brien, fifteenth Lord Inchiquin, who is the heir of the Kings of Thomond; and Dermot Bourke, Earl of Mayo, who is sprung (it is said) from Toby of the Ships, son of Grace O'Malley. Besides these there are among them the representatives of the Geraldines, the Butlers, the La Poers, the FitzMaurices, and of the Galway Tribes; and of the later English of Ireland, such as the Chichesters and the Beresfords, and of many Cromwellian families who have been for a long time notoriously Irish. But you will not see the whole merit of the phrase unless you bear in mind how England has always treated that Garrison.

The Old Irish might have looked for hostility, though as a matter of fact they had showed little enough in the beginning. Is it not recorded that all the five Royal Clans, the MacMurroughs of Leinster, the O'Connors of Connaught, the O'Neills of Ulster, the O'Melaghlins of Meath, and the O'Briens of Munster, welcomed the Normans? But the English of Ireland, the Normans and the others that copied them in the following centuries, had reason to hope for goodwill. Yet in 1342, one hundred and seventy years after Strongbow landed, King Edward III. "resumed" all their estates and only restored them ten years later because he had found the confiscation impossible. Next Lionel of Clarence tried to confiscate part of the realms of the De Burgos in Connaught. Then France and the Wars of the Roses distracted England's attention. Under Henry VIII. there was talk of driving all the Irish beyond the Shannon, and colonising the rest of the country anew; but he, either through wisdom or on account of the engrossing nature of his private affairs, refrained from this, and was content with the estates of the Geraldines. Next Mary Tudor appropriated and colonised Queen's County and King's County, naming them after herself and her husband, Philip of Spain; and then Elizabeth waged an exterminating war, in which, like the Geraldines of Desmond, many English of Ireland were despoiled for the benefit of the English of England. Next James I. confiscated and sold Ulster. Under his son, Charles I., Strafford attempted to find a similar source of profit in Connaught by invalidating the titles under which the English of Ireland held their lands. Then came Cromwell with his Partition, and after him William of Orange. Then came the Penal Laws, which succeeded in ruining most of the Catholic Old Irish and English of Ireland. After all these signs of favour came the Encumbered Estates Act, and other remarkable benefits. Was all this the Garrison's pay?

Without discussing the question whether they deserved it or not, we can conclude that the landlords shared the ill-luck of their country. As for the peasants, their part of it is sufficiently known. Both these classes may now be ranked among the Ruins of Ireland. Why has nobody prospered there except in that Fort of the Strangers, the Protestant North? Spenser wrote, "They say it is the Fatal Destiny of that Land that no purposes whatsoever which are meant for her good will prosper." After three hundred years we have all the more reason to put trust in that saying. Yet

when the Irish leave their home many are fortunate. The fact is, that while they are in Ireland they share the doom of the Celt.

The Irish Celt is a spendthrift of life and gold, valuing neither. That is the clue to the tangle of Ireland's history. He is aware of the solitude in which every man lives and dies: other men may not heed it till the last hour when it is patent to all; but the look of his country keeps it before him. He knows that companionship must be incomplete and that love is vain. The Highland Scots have a saying, "As loveless as an Irishman"; and though you might reject this as unjust, if you thought of the clinging companionship and the mutual tenderness to be observed in every class, for all that it goes to the root of the matter. In Ireland we are gregarious because we are solitary, and loving because we commiserate our universal deprivation of love. This it was that guided our saints, who chose to dream alone of a love that was enduring and perfect.

Our ruins are dear to us because they denote the vanity of human endeavour. If you could make our home prosperous and crowded with factories, it would be Ireland no more. The English Black Country is like the crest of a volcano, whether the smutty shafts vomit foul smoke or are topped by horrible flames in the night. You feel that if it was ever green and pure, that was because the fire beneath had no outlet. But in Ireland the rare smoke of a factory seems as alien and futile as does a little black cloud on a fine summer morning. You feel that the air is but briefly contaminated, and that in the noisiest place silence remains supreme.

In fortunate countries the ruins appear accidental. When in England you come on one of the few surviving wrecks of the monasteries, you are apt to believe that it must have been retained as an ornament, and to wonder why no one has turned it to agricultural uses or pulled it down for the purpose of employing the stones. There was a time when the Religious Orders possessed a third of the soil of England, and had many hundreds of stately homes in the shires; but now, though a few of these are inhabited still, not by monks, and though there are chapels that once adjoined monasteries and now are preserved because they are useful as pigstyes or barns, the majority of their buildings have vanished. In Ireland the ruins appear essential: no landscape would seem Irish without them. In their seclusion they dominate the sad hills around. Silent though they are, they express the spirit of Ireland. Go to Cashel, and try to imagine how different the landscape would seem if the lone Rock and its venerated burden were gone. The Rock itself was cast there by some supernatural being, either an ancient god or the Devil (so it is said); and if you venture to doubt this, you will be silenced by the fact that it rises suddenly from a cleft in which nothing resembles it, while there is visible in the distant mountains a hollow shaped in its likeness. It stands among fertile and unfortunate moors. This was a land worth many blows, and innumerable ones were exchanged for it; but now it is as empty and silent as the fortified cathedral that once crowned Cashel of the Kings. Without that tall ruin, the scene would resemble a church lacking a spire. Paint Devenish and then delete the ivied remains from your picture, and you will see that it is dead and has no longer a soul.

These are the solid ghosts haunting our land. In our ignorance we are not told by them of definite sorrow, but of a vague load of calamity. Some have no history extant: nobody knows what was the meaning or the use or the date of the Round Towers that stand mysteriously unimpaired in our glens. Learned men have decided that these were built either as places of refuge from the Danes, or as belfries by the primitive monks, or by the Druids for the purpose of lighting the Beltane Fires that should answer those that shone on the hills, or by the earlier priests whose worship was that of the Phoenicians, or for some other reason in times of which nothing is known. If you lived in dark Connemara, and believed that the solid dead were your neighbours, and might at any time come to your house and sit indifferent and cold by your fire, it is not probable that you would display much commercial activity or be greatly concerned with the little and brief affairs of the living. So our ruins remind us that all our joys and afflictions are little and brief.

All who settled in Ireland found themselves apart and enjoying an unnatural youth. As a man finds refreshment in visiting the haunts of his boyhood, and feels that he would have mOre if he could renounce the unwelcome wisdom of age, so they took pleasure in ways that had been dear to their fathers a long time before, and were by no means unwilling to adopt them in turn. Because this was the Oldest of Islands it was the youngest: the life in it always remained simple and kind and unwise. Here they learnt the old wisdom that others had rejected as folly. Here they found Tyrnanoge, the Land of the Young, and forgot. When the Greek wanderers tasted the Lotus on that other enchanted shore where it was always afternoon, they relinquished all their anxieties and all their possessions. So the settlers became free from old ties and burdens, and with a fresher delight, for it is always morning in Ireland. Nor was there any gloom to deject them, for in that country of sorrow there is a happiness that is not of this world; in the core of its affliction there dwells a penetrating joy.

These things conquered the conquerors, and by so doing made the English attempts ineffectual, since the new garrisons were each in their turn enlisted in the ranks of the Irish. And this is the justification of England's behaviour towards each of those garrisons. All who settled in Ireland suffered because they ceased to be English. Yet they had compensations for that; and even now when so many of them have acknowledged a final defeat, and reverting to ordinary life have relinquished that separated home, the enchantment is felt by them still, though in other places there is wealth to be had and things that many covet.

The secret of Mysticism is to be found in an exceeding simplicity. So, too, the young ways of Ireland, like those of children, are only perplexing because they are too simple to be understood by the old. Children are not reluctant to quarrel, and yet they have an abiding peace rarely to be known by their elders; even though the toys are all broken, you will find them content. In the same way we are peaceful and contented in Ireland: under all our misfortunes we have the buoyancy of childhood and Spring. Here are some verses I made when I should have been rejoicing in London and all its rich accumulation of grime, and with them I finish this book; not gladly, for if you have been able to find no pleasure in reading it, you can take comfort in the knowledge that writing it was a pleasure to me.

"In the Island o' Ruins, remembrance o' grief

Hallows the hills, as when summer is slowly

Fadin' in darkness, the fall o' the leaf

Makes the woods holy.

"Green are the woods though the mountains are grey;

Spring is too young to remember old doin's.

Ah! but I wish I was roamin' to-day

In the Island o' Ruins!"

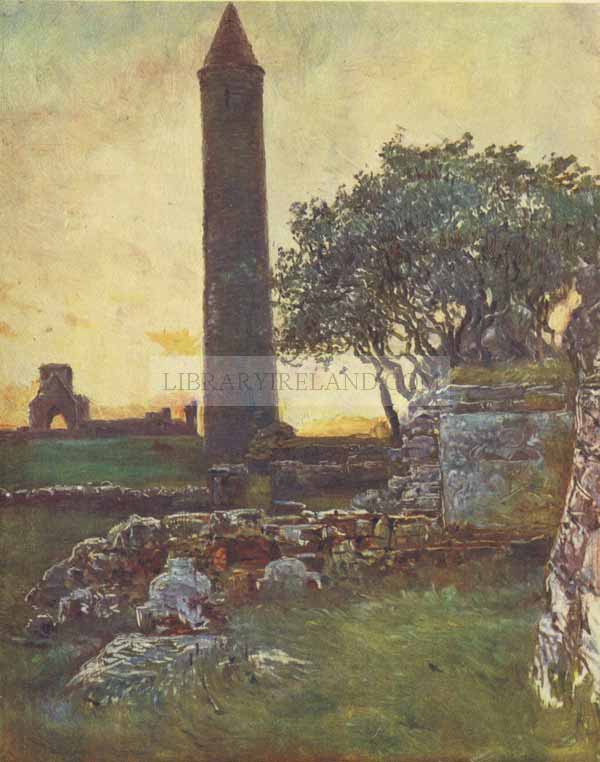

THE ROUND TOWER ON DEVENISH ISLAND

WHICH is situated on Lough Erne, about two miles from Enniskillen, is said to be one of the finest in Ireland. Near it are the remains of two churches, around which are burial grounds still used. The funerals of those buried here are very impressive, and are conducted in a procession of boats over the lake, starting from the Port of Lamentation, in Portora, Enniskillen. In the lower churchyard are some interesting tombs, and a stone coffin, in which some people lie down, because it has been a saint's bed, and is so called. In the upper yard there is a small stone cross of about seven or eight feet high, unlike the ordinary Celtic cross, and of elegant design and proportions.