The Highlands of Donegal

TO avoid any appearance of partiality, I shall begin my brief description of Ireland in the remote nook of the North, among the ultimate mountains of Donegal. The name Donegal means the Fort of the Strangers. This detached nook has been the fort of the Irish, those perpetual strangers, the one fastness in which they have remained stubbornly rooted. It was ramparted from the rest of the country by difficult heights, and it was uncoveted, because it was mainly barren and mountainous, so it did not allure conquerors. It was included, of course, in the Partition of Ireland, when Oliver Cromwell attempted to herd the Irish Nation in Connaught while he gave the rest of the country to others. This part was one of the many he bestowed on his veterans; but they were not pleased with it: smooth meadows would have been more to their mind, and, for obvious reasons, they did not enjoy being so far away from their friends. They were not favourably impressed by the natives.

A good deal depends on the point of view; and even the warmest admirer of the peasants of Donegal will allow that some of their traits would be unpleasing to conquerors. Only a very obtuse or heroic man would have wished to find himself living among them as an enemy, and in possession of their land, when the winter made their dark valleys isolated again. So the few veterans who travelled so far went back to their comrades with a discouraging report; and in this nook Cromwell's benevolent plan failed. The shares he assigned were sold cheap; and the former inhabitants, though they had to recognise new landlords, remained undisturbed. This long immunity kept their stock pure; and their character now is the more deserving of study, because it can be taken as representative of that of the Irish before they were broken. This stock has been free from any alien infusion; it has not been weakened by blows, nor degraded by adversity.

No doubt, that character has been somewhat modified by compulsory peace. In the old days this land was Tir-Connell (Donegal then was only the name of a little fort set in a green place under mountains at the head of a long sheltered bay), and in this wild refuge the warlike O'Donnells were kings. The clans of Tir-Connell were great fighters: far counties remembered their devastating raids. When those congenial pursuits were forbidden, the race must have become gradually quiet. When the shrill pipes of the O'Donnell no longer excited the wailing whoop of the war-cry, men must have been subdued by the silence of the desolate places. Yet, while making allowance for this, we may conclude that the calm Highlanders greatly resemble the fierce kilted men who obeyed the Dark Daughter or her terrible son, Red Hugh. The clans of Tir-Connell, though mighty in war, were law-abiding and laborious in peace. Learning was held in great honour among them. The ruins of Kilbarron Castle, between Donegal and Ballyshannon, still speak of its former lords, the O'Clerys, three of whom were among the Four Masters whose Annals are still renowned; and on these shores there are many wrecks of abbeys and colleges. Those clans honoured piety too, and were, above all things, religious.

An Elizabethan map showed the territory of the different tribes by displaying the armed figures of chiefs: MacSwiney Fanad was depicted on his mountains, and near him, the head of his house, Owen Oge of the Battle-axe. These portraits gave the English notion of men who were supposed to be savages. This method of illustration was natural, for Queen Elizabeth's Deputies were only concerned with the question whether Owen was eager to wield his battle-axe, and they knew little about the men he commanded; but if the maker of that map had been acquainted with Donegal and had wished to draw a typical figure, he should have chosen Columba. Those grim chiefs bulked huge in their times, but now are commemorated only by names. For instance, there is in the high cliffs by Horn Head a cave through which the sea plunges in storms, with a noise like the report of a cannon; and it is called MacSwiney's Gun. You will find that the peasants know little about MacSwiney; but ask them about Saint Columba, and you will see them familiar with the whole of his life, though his bones had crumbled to dust hundreds of years before the English began their amiable efforts in Ireland.

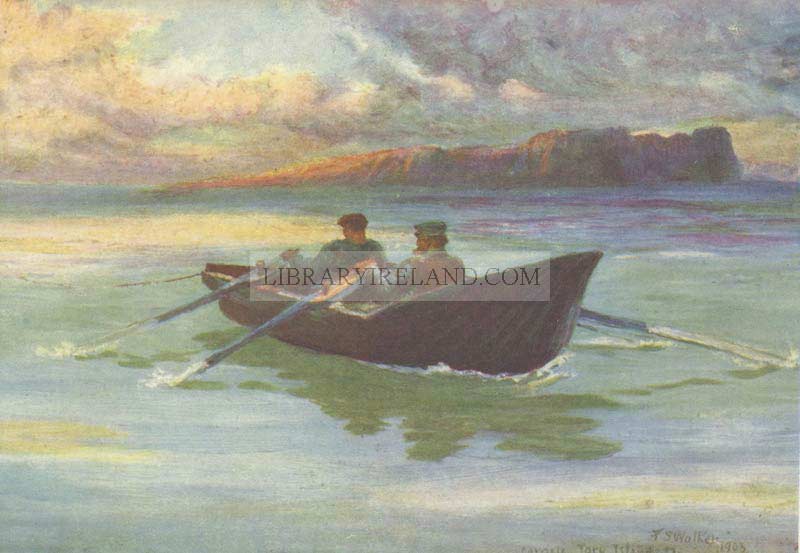

A CORACLE, TORY ISLAND

THE coracle or curragh varies in shape on various parts of the coast. At Galway it resembles a section of a walnut shell, but in Donegal the high prow is for the purpose of resisting the great waves of this wild coast. It is very light, without a keel, and built on a frame with wicker sides covered with skin or tarred canvas. It costs about £2 10s.

Columba, or Columbkille, the Dove of the Churches, was born in the year 521, by Lough Gartan. He became a monk and built his first monastery at Daire Calgach, the Oak Grove of Calgach, a place afterwards known as Daire Columbkille, in his honour, and now, having passed under a different influence, called Londonderry. Then he built several others, as at Gartan or Raphoe. These would have kept his memory green for a time; but the persistence of his fame is due rather to his warlike exploits. He caused two desperate wars, and was therefore exiled from Ireland, and betaking himself to Iona, peopled that solitude with monks and began the conversion of England. He was a lover of peace, ready to fight if the occasion was given; he was just and would not suffer injustice, was a poet, a scholar, a builder, hot-blooded and calm, energetic and passionately fond of his home. In all this he was a typical son of Donegal; and that is why he is still loved and revered, while less faulty saints are forgotten.

On a hill over Lough Gartan, there is a long slab of rock called Ethne's Bed, of which it is told that his mother lay on it when he was born; and it is believed that those who sleep on it will be proof against home-sickness for ever, for which reason many emigrants bound westward have spent nights on it under the stars. This blessing is said to have been earned by his tears when he longed for his wild home during his banishment in wilder Iona; and the belief in it is a sign how that sorrow was understood by his people. Yet the place most associated now with his name is not Gartan, but Glen Columbkille, above Malinmore Head, where the heavy waves roll from the West. That deep glen is strangely calm, though it echoes the call of the sea. Often it echoes prayers and hymns too, for it is haunted by pilgrims. Twelve Crosses, tall shafts of grey stone, stand in it on hillocks: these are his "Stations," at which many still kneel as others have done, year after year, since he trod that smooth turf full of flowers. That place was hallowed long before he was born. Dark little hovels made of piled stones are scattered over it, and these (it is held) are of a date earlier than his. Even those Crosses are said to be Druidical monuments converted by him. All this country abounds in Cromlechs; and it seems certain that here, as at the Oak Grove, he chose a Sanctuary that once had beheld the rites of the Druids. The Glen seems immemorially sacred; it is like a vast church roofed by the sky. The far sound of the waves and the voices of the pilgrims are hushed, and only remind you that silence is absolute there.

GLEN COLUMBKILLE HEAD

ST COLUMBKILLE or Columba, after whom this headland is named, learning that a neighbouring king had an illuminated manuscript of the Gospels, asked for a copy of it, but was refused. He, however, obtained one by stealth, which was claimed by the original owner, and this right denied led to war. The Gospels in the king's army were carried instead of a standard, and thus called "The Battle Book." Neither side being victorious, the cause was submitted to Cormac, king of Meath, and his decision was: "As the calf belongs to the cow, so does the copy to the original." This being against Columba, he was further banished from Ireland until he had saved as many souls as were lost by war. It is said that it was from Glen Columbkille Head that he departed with his followers to Iona in Scotland.

Glen Columbkille is the heart of Donegal. And if you wish to know the hearts of the people, you can best understand them in that solitude. The neighbouring cliffs are sheer walls. Glen Head stands erect, eight hundred feet high, and is dwarfed by the precipitous flank of Sleive League over Carrick. From the brink of Sleive League you see the waves flash eighteen hundred feet below. Nor are the inland heights gradual; Mount Muckish, for instance, and Mount Errigal have sides that resemble gigantic fortifications. The granite walls by the sea are grimly defensive. Yet many smooth strands are beneath them, and many calm inlets, such as Lough Swilly, the Lake of Shadows, are sheltered. The shadow of the mountains beside it gave Lough Swilly that name; but it is justified also by the memories of the chiefs of Tir-Connell. Many were the battles they fought beside it: Red Hugh, that firebrand of the mountains, was captured on it in his boyhood, and it was made famous by the Flight of the Earls. Down to its shore, on a dark September morning in 1607, came the great Earl of Tyrone and his confederate, the Earl of Tyr-Connell, when having abandoned hope, they forsook Ireland for ever. Their long struggle was over; and for them only remained brief exile in defeat and then rest where the high Church of San Pietro in Montorio looks over Rome. From this quiet water they passed away and were shadows; but the din of those battles and the passionate laments of that morning did not avail to break the peace of this haven. They were momentary; but that was eternal. In all these indomitable Highlands you feel that there is peace at the core. Those savage ramparts protect the level sands and the shadowy bays and the dedicated hollows; the most stern and the wildest of all guard Glen Columbkille.

The Highlanders, as you see them to-day, are calm and laborious, they are peaceful, and yet it is wiser not to meddle with them. This is a hardy stock and a silent one, moulded by solitude and a seafaring life. Because they live among rocks, they have to dare the North Atlantic for food, or cross the rough Moyle to cut the harvests of strangers. They do this with little reluctance, for they have been strengthened by the vigorous air: here you find none of the terror with which the fishermen of Connemara regard the ocean; neither will you observe their despairing melancholy. If these have a melancholy look, as they have often, you feel that their sadness is a pleasure to them and a wholesome one. They have the brave pride of independence. In no land will you see a more dignified hospitality. Even the poorest man is proud of his home, and with reason, for however rude it may be, it represents infinite toil. You will find their crops growing in unnatural places, on the sandy edges of cliffs and up in the mountains between clusters of rocks, and you will learn that some of these high fields have been made by the simple process of carrying the soil from beneath. You will see young girls digging potatoes, or tugging the nets, or carrying heavy creels on their backs up the long mountain paths; and the rough cabins are musical with the murmur of looms. Here the old ways of extracting dyes from the heather are followed, and so are the old methods of weaving that are not to be rivalled by any machine. When there is such industry, one might expect comparative wealth; but that is not to be found. This is one of the poorest peoples on the face of the earth, and one of the happiest. Hard though their life is, it is lit by an inner content. Though their home is so stern, they can imagine no worse calamity than exile from it. Life is full of labour for them; but the peace of Glen Columbkille abides in their hearts.

There is in these Highlands a singular freshness. You feel as if the air had been kept from any taint by the barrier that holds them secluded; this is a morning country still undefiled. It is no wonder that its people are choked by the thick air of other lands and are fain to return even though they have slept on Ethne's Bed under the stars. Neither can they find anywhere else a country more beautiful, for wild though it is, it has a magical colouring, and if that is subdued it lends the more charm to the vivid face of the sea. You will never forget Horn Head, if you see it on a bright windy morning, when the many colours scurry across it and beneath it the sea flashes and varies and the long yellow sands of Tramore glitter like gold.