General Humbert lands in Killala

Humbert lands in Killala with a Thousand Men—Career of the Hero and Composition of his Army—Bishop Stock's Testimony to the Invaders.

HE town of Killala is situated on the bay of the same name, on the coast of County Mayo. It is an ancient bishop's see, and was founded in almost prehistoric times by Amhley, a prince of the district, who, according to tradition, was converted by St. Patrick, together with seven hundred of his subjects, in a single day. In 1798 there still remained some relics of a bygone age. Among them were the ruins of a "round tower," erected in the sixth century by the eminent Irish architect and divine, Gobhan, on a knoll in the centre of the town. From the base of this elevation three roads diverged—the main street taking an easterly direction, winding by the churchyard wall, down a steep hill to the bishop's castle, another aged structure dating back many centuries, that but for constant repair would long since have crumbled into decay; a second road running south to the "Acres," a distant height on the border of the town; and a third pursuing a westerly course to the banks of the Owenmore, two miles away. This river is crossed by a majestic stone bridge of eleven arches at the village of Parsontown, from which point the road branches east, following the windings of the stream for nearly a mile; then bending northwest parallel to the Bay of Rathfran—an inlet of the Bay of Killala—it merges into the highway of Foghill. On the banks of a creek at the western extremity of the Bay of Rathfran stand the moss-grown ruins of Kilcummin, a cell built by Cumin in the seventh century.

It was within sight of this romantic spot that, early in the afternoon of the 22d of August, 1798, several fishermen, while busy repairing their nets, were surprised by the appearance of three large war-ships suddenly rounding a neighboring promontory and casting anchor two hundred feet from the shore. For some days past vague rumors had floated through the air that a French fleet had left La Rochelle and was on its way to the Irish coast. At first sight, therefore, the men decided that this must be the enemy. But a second glance revealed the British colors flying at the vessels' bows, and, eager to earn a few pennies, they left their work and at a brisk gait crossed the high ground that hid the bay from the town of Killala. Reaching this place they made a straight line for the dwelling of the Rev. Dr. Joseph Stock, Protestant bishop of Killala, and in all respects the leading inhabitant of that section of the country. This excellent man, in spite of his intense Protestantism and fealty to the government, harbored a deep resentment toward the ultra-loyalists, whose machinations were furnishing a plausible pretext to the Romanists for distrust and hostility toward their Protestant brethren in general. Orange lodges for the avowed purpose of stirring up strife were being started in Connaught, and the bishop was opposing them with might and main. On this very day he was busied in entering a protest, in his "primary visitation" charge, against the first sentence of the oath by which Orangemen are banded together, viz.: "I am not a Roman Catholic." To his broad and liberal mind such a sentiment had too pharisaical a ring. It sounded too much like: "Stand off, I am holier than thou!"(4)

Greatly pleased were the reverend gentleman and his guests—clergymen from the vicinity—at the news brought by the fishermen. A British fleet in the bay meant an end to all danger from the French. It meant an end to the condition of suspense into which the Protestant population had been thrown by the persistent rumors from all sides. Even among the servants in the bishop's household the belief had been firm that something unusual was impending. A Protestant servant-maid, married to a Catholic, suspected of affiliation with the rebels, had circulated the report, and Mr. William Kirkwood, the local magistrate, had in so far credited it as to keep under arms, as a precautionary measure, the entire body of yeomanry under his command, together with the Prince of Wales' Fencibles under Lieutenant Sills—numbering about fifty men, say the loyalist writers, but numbering many more, say other authorities.(5)

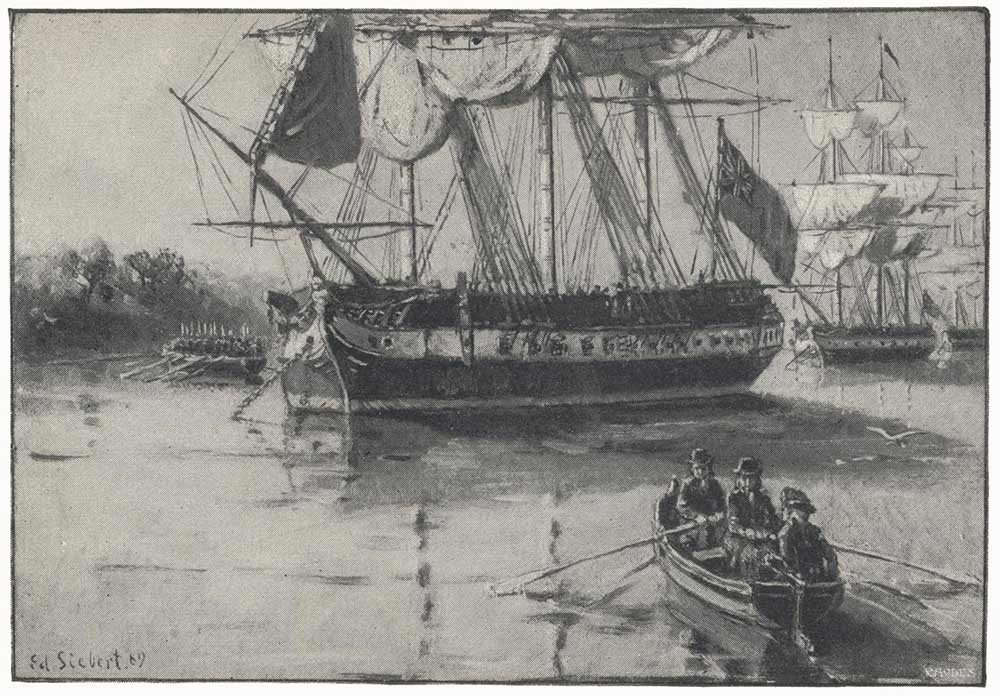

"The three stately ships in the foreground, and the verdant, undulating hillocks bordering the shore beyond, formed a charming picture."—Page 29.

Impelled by a desire to pay their respects to the officers of the squadron—possibly also to extend the hospitalities of the castle—the bishop's two sons, Edwin and Arthur Stock, ran down to the wharf and jumped into a fishing boat. Here they were joined by the port surveyor, Mr. James Rutledge, and a few minutes later the three were skimming over the placid surface of the bay on their way to the men-of-war. It was nearly three o'clock, and the sun beat on the water with a fierce, white glare. The three stately ships in the foreground, and the verdant, undulating hillocks bordering the shore beyond, formed a charming picture. As the small boat came within hailing distance Rutledge commented on the peculiar construction of the vessels, all three apparently frigates. His surprise was increased at the sight of a number of minor craft plying to and from the shore, laden with blue-coated soldiers, who formed in line at a short distance from the water's edge. Still suspecting nothing, the three approached the nearest war ship, from the bows of which numerous shaggy heads stared expectantly.

"Nice-looking fellows for British man-of-war's men!" remarked Rutledge, derisively.

His hailing cry was answered in a deep bass voice, with an unmistakable Irish brogue. A rope ladder was lowered, and the three men were hoisted on deck. But what was their astonishment to find, in lieu of a natty British captain and crew, a row of gaunt and sallow men in the uniform of the French army, one of whom stepped forward and informed them, in good Dublin English, and in the name of his superior, General Jean-Joseph Humbert, there present, that they were on board the French frigate Concorde, prisoners of war in the hands of France.

The prolonged absence of the bishop's sons and the surveyor soon awoke suspicions in the minds of the loyalists of Killala. By four o'clock the excitement was at fever heat. The inhabitants had gathered on Steeple Hill, where Captain Kirkwood with his corps, in full uniform, were awaiting the issue of events. Two officers from the garrison of Ballina, eight miles away, who had seen service at the Cape of Good Hope and were judges on matters naval and militarv, were eagerly interrogated by the spectators, but they could form no authoritative opinion as to the nature of the vessels. "Here," said Captain Kirkwood, handing his telescope to an old denizen of the town who had fought under Howe and Rodney, "here, tell me what these vessels are." "They are French, sir," returned the sea-dog. "I know them by the cut and color of their sails." Turning to leave the crowd, Captain Kirkwood was questioned by Neal Kerugan (a noisy malcontent, and afterward a leader of the insurgents) as to the nationality of the frigates. "Ah, Neal," replied the captain, significantly, "you know as well as I do."

Just about this time a peasant covered with dust and sweat rode furiously into Parsontown with the startling information that troops in blue uniforms were landing from the ships, and were distributing arms to many of the inhabitants who had joined them. Presently this fact was confirmed when a solid body of men were descried moving along the road leading to Killala. Now hidden in the hollows, now sharply outlined against the sky, their arms flashing in the rays of the setting sun, they marched slowly but steadily onward, preceded by a single horseman—a large, robust-looking man, dressed in a long green hunting frock and a huge conical fur cap. On meeting parties of the townsfolk he stopped and saluted them in the Leinster patois: "Go de mu ha tu" (How do you do). Close upon his heels rode a French general—Sarrazin—and his aide-de-camp, one Matthew Tone, both seemingly much amused at the other's successful handling of the Irish tongue. When they had crossed the Parsontown bridge General Humbert drove up in a gig and ordered three hundred of his men to bivouac on the green esplanade in front of the village, while the remainder were sent on to Killala.

Twilight was falling on the world, and the gentle voices of the evening insects were singing a lullaby to the drowsy earth when Sarrazin's stalwart grenadiers and infantry marched down the hill of Mullaghern and advanced upon the little town. Captain Kirkwood, informed of the true state of affairs, hastily gathered together his yeomanry and the Fencibles, and ordered them to a commanding ridge on the outskirts; but soon deciding this position to be less advantageous than one within the town itself, he fell back and took a stand at the top of the decline leading to the castle. He showed his wisdom, for no better situation could have been selected for a retreat. Sarrazin, on arriving within gunshot of the enemy, made his dispositions. He sent a detachment under Neal Kerugan—now a full-fledged rebel—to occupy the "Acres" road, to turn the British, if in position, or cut them off in the event of their retreating. He stationed a handful of sharpshooters on the deserted ridge, and sent the green-coated horseman referred to before forward to reconnoitre. Through the winding streets the chasseur dashed. The target of many a bullet, he reached the marketplace unharmed. Here he was challenged by a young gentleman of the place in yeoman's uniform with: "What do you want, you spy?" The voice of war is the scream of the bullet, and the answer, conveyed through the medium of a pistol, was both convincing and silencing. One more dash in the face of death to inspect the enemy's position, and this modern Achilles, with his heel well booted, was back among his companions, where he related with much unction that "though he had been in twenty battles, he had never before had the honor to receive the entire fire of the enemy's lines."(6)

By this time the action had begun. The sharpshooters were showing their mettle, and the grenadiers, who had headed the attacking column, deployed on the main street, in the centre of the town. There they were opposed by the English with a faint-hearted fire. Captain Kirkwood, alarmed at the indecision of his men, ordered them in excited tones to charge. The command found no response. The line hesitated, wavered, broke—and in a moment the whole force were skurrying toward the castle gates. In the scramble the town's apothecary, a respectable citizen of the name of Smith, was laid low by a bullet from a French trooper, and the Rev. Dr. Ellison, of Castlebar, an Anglican clergyman and guest of the bishop, who had bravely appeared in the ranks, musket in hand, received a wound in the heel. At the castle gates the fight was resumed, this time with some spirit. The defenders endeavored to barricade the entrance, but notwithstanding the unquestionable bravery of their commanders, one of whom, Lieutenant Sills, wounded an officer of the attacking party, the gate was forced open and what remained of the British laid down their arms. These were nineteen in number. The rest had been killed or wounded, or had fled. Among the latter were the two officers from Ballina, who carried the news to their commander.

An interesting scene occurred when the smoke in the court-yard had cleared away. A tall man of resolute mien, wearing a general's epaulettes, who arrived at the conclusion of the fight, accompanied by a numerous staff, and who proved to be Humbert himself, suddenly ordered the troops in stentorian tones to ground arms. Then turning to the three prisoners, Mr. Rutledge and the Stock boys, who had been brought with the column, he asked through an interpreter where the bishop could be found. Naturally the badly frightened men were unable to supply the information; but the suspense was of short duration, for presently the worthy prelate emerged from the bushes of his garden near by. He was at once assured by the same interpreter, one Bartholomew Teeling—of whom there will be occasion to speak further on—that no harm was intended; and as he stepped forward Humbert extended his hand. What improved matters was the bishop's knowledge of French, an advantage which, combined with his honest exterior, impressed the general favorably. At all events the latter's first words breathed kindness and good will.

"Take my word for it," was his assurance, "that neither your people nor yourself shall have cause to feel any apprehension. We have come to your country not as conquerors, but as deliverers, and shall take only from you absolutely what is necessary for our support. You are as safe under our protection as you were under that of his Majesty, the King of England."

All contemporaneous authorities, be they English or Irish, loyalist or revolutionist, agree that, to the honor of the French name, this promise was religiously kept. History furnishes few examples of so scrupulous an observance of the rules of civilized warfare, so thorough a respect for the rights of the conquered, as distinguished the operations of General Humbert and his little army.

And now a few words regarding the origin and organization of this expedition, which for a short period threatened to crush out England's supremacy in the Emerald Isle. In the preceding chapter reference was made to the several isolated attempts on the part of the French Directory to land an invading army on the Irish coast. The last one had been balked by Bonaparte's designs on Egypt. Thereafter the demands for aid of the Irish emissaries in Paris only became more urgent and incessant. Owing to the Egyptian expedition having well nigh drained the republic of money, ships and stores, several months elapsed before a fresh armament could be equipped. This time it was decided to send out two small advance forces, and to follow them up later with a main body. For that end General Humbert was stationed at La Rochelle with about 1,000 veterans, while General Hardy took up quarters at Brest with 3,000 soldiers, mainly ex-convicts. The gros of the expeditionary force, numbering 10,000 men, was placed under the orders of "Kilmaine le brave" as his companions-in-arms delighted to call him. This distinguished officer was an Irishman by birth, named Jennings, who assumed the "nom de guerre" of Kilmaine upon entering the French military service, where his splendid achievements on the frontier of the Austrian Netherlands elevated him to the rank of lieutenant-general.

Of these three separate forces only the smallest, under the orders of Humbert, was destined to reach its goal. Humbert himself, if some of his biographers are to be believed, was far from being the ideal hero of a romance of war. To his many brilliant parts were allied vices that in any but a disorganized state of society must have disqualified him for every position of honor. Beset as she was at that epoch with enemies on all her borders, France had need for every citizen who could contribute to the salvation of the fatherland. Purity of character was little in demand, and the man of ability, however unscrupulous, possessed better chances of advancement than his honest but mediocre neighbor. The authorities are divided both as to Humbert's birth-place and the date of his birth.(7) From one source we learn that he was born at Rouveroye, November 25, 1755; from another that he first saw the light of day in 1767 at Bouvron (Meurthe). But this is a small matter. It appears to be beyond dispute that young Jean-Joseph Amable Humbert was a "hard character" from the very start, and that he brought much sorrow on his grandmother, on whom the care of the youth devolved after the early death of both his parents. After leading her a life of misery, he left her roof at the age of seventeen to enter the service of a cloth merchant in a neighboring town. He had shown an early disposition to pay undue attentions to the fair sex, and his handsome face and lithesome figure had stood him in good stead in these matters. Away from home the temptation grew stronger, and we soon find him dismissed from his employ for acts of gross immorality. The youth returned to Rouveroye,(8) but his reputation had preceded him, and he saw every door closed at his coming.

For the second time he left home to seek his fortunes elsewhere, and again, as before, his ill-conduct brought with it a summary dismissal from a steady situation in a hat factory in Lyons. The young man now became a social pariah. These were still ante-revolutionary times, and a disgraced employé found it difficult to secure recognition anywhere. Starvation stared our hero in the face. In this dilemma a happy thought struck him. He had casually discovered that skins of certain animals, such as rabbits, young goats, etc., were in great demand in the glove and leggings factories of Lyons and Grenoble. He therefore started out with a few francs in his pockets, and wandering among the remote villages of the Vosges district, purchased at low rates as much of this merchandise as his means would allow. A handsome profit on the first batch encouraged him to undertake a second and a third tour, and after awhile his figure became familiar throughout a large tract of the country.

At last there resounded the tocsin of the great revolution. For once the heart of the wanderer seems to have throbbed with a grand impulse. The fires of ambition that had lain dormant in his breast blazed forth in all their fury. Abandoning his now prosperous pursuits, he threw himself into the great movement. Peasants who had bartered and bargained with him, maidens who had known him as a peripatetic swain, were electrified by the earnestness of his exhortations. He joined one of the first volunteer battalions organized among the Vosges, and by his active republicanism no less than by his military qualities, quickly rose to be its chief. With the rank of Maréchal-de-camp, he accompanied the army under Beurnonville which in 1793 burst into the territory of Trèves. It was here that another bad side to his character disclosed itself. On the field of battle brave to a fault, utterly regardless of his own person and ever ready to embark in the most perilous enterprise, in camp he proved himself an arch intriguer. Anxious to secure promotion, he secretly sought permission from the Directory to act as an informer on the movements of his comrades-in-arms, averring that many were guilty of lukewarmness in the cause of the republic. Beurnonville, however, got wind of his subordinate's schemes, and wrote a scathing letter of denunciation to the military authorities in Paris, characterizing the action as the height of baseness (le comble de la scélératesse) on Humbert's part, and demanding his immediate recall.

Concluding a modus vivendi between the two to be henceforth out of the question, the Directory reluctantly acceded to Beurnonville's request, and for some months Humbert prowled around Jacobin headquarters in Paris, awaiting fresh employment.

His persuasive eloquence and apparent earnestness as a promoter of republican doctrine made him a favorite there. In April, 1794, he was promoted general of brigade and given a command in the Army of the West. Of all the different forces sent out to combat the enemies of the republic, that which opposed the fierce chouans of La Vendée encountered the greatest dangers and obstacles. Victor Hugo, in his Légende des Siècles, has fittingly described the struggle as a combat "'twixt the soldiers of light and the heroes of darkness;" and in truth, were it not for the atrocities committed on both sides, this campaign might take its place among the most brilliant annals of ancient chivalry. Neither party asked nor expected quarter. It was a war to the knife, without truce, without respite. Humbert showed himself equal to every emergency. He hunted down the foe with unabating ardor, tracked him into his marshy lairs and forest fastnesses, and won the admiration of the entire army by his personal disregard of danger. Alter many months of hard fighting, the Convention decided to adopt a milder course toward the insurgents, and on March 7, 1795, a treaty was signed at Nantes by which, in return for certain privileges, the Vendeans agreed to acknowledge the republic. The pause in hostilities was unfortunately of short duration. Cormatin-Desoteux, the chouan leader, having repeatedly violated several provisions of the treaty, Humbert effected his arrest, and sent him in chains to Cherbourg.

This act, coupled with the discovery of a traitorous correspondence between the Vendean leaders and the English Government, fanned the smouldering embers of factional hatred, and by the beginning of summer the civil war was renewed with increased ferocity.

As second in command under General Hoche, Humbert took part in all the operations at Quiberon against the Anglo-Emigrant Army landed by a British fleet. He inflicted a crushing defeat on the invaders on July 16th, from behind his entrenchments at St. Barbe, and on the 20th stormed the fort of Penthièvre, thereby destroying or capturing the entire emigrant force. The subsequent massacre of prisoners, which will ever remain a blot on the escutcheon of the republic, is, however, not to be laid at his door. The horrible act was ordered by the two General Commissaries, Blad and Tallien, and was executed against the wishes both of Hoche and Humbert. The latter had not made himself popular among the Moderatists while in Paris, and the opportunity was seized upon by the newspapers of the Clichy party to hold him up to public contempt. His early vocation was thrown up against him, and the former "marchand de peaux de lapin" became the target of many a satire in prose and verse. All these assaults were fruitless, however. If anything, they tended to cement his influence with the Directory. In any case he was made a general of division, and selected, a year after, to accompany Hoche in the expedition to Ireland. Reference has already been made to this event, and to the failure of the French to effect a landing. One of their ships, the Droits de l' Homme, a seventy-four, was intercepted on the retreat by two English vessels, and between their cross fire and the raging of a terrific storm, she was completely wrecked. Of the 1,800 men on board, barely 400 escaped with their lives, and among these was General Humbert.

Such was the career of the man upon whom now devolved the task of bearding the British lion in his den. To complete the picture one cannot do better than quote the following estimate of his character, contained in an anonymous pamphlet published in 1800, the authorship of which has been brought home to Bishop Stock, of Killala:(9)

"Humbert, the leader of this singular body of men," says the writer, "was himself as extraordinary a personage as any in his army. Of a good height and shape, in the full vigor of life, prompt to decide, quick in execution, apparently master of his art, you could not refuse him the praise of a good officer, while his physiognomy forbade you to like him as a man. His eye, which was small and sleepy (the effect, probably, of much watching), cast a sidelong glance of insidiousness, and even of cruelty: it was the eye of a cat preparing to spring upon her prey. His education and manners were indicative of a person sprung from the lower order of society, though he knew how (as most of his countrymen can do) to assume, where it was convenient, the deportment of a gentleman. For learning he had scarcely enough to enable him to write his name. His passions were furious, and all his behavior seemed marked with the characters of roughness and violence. A narrower observation of him, however, served to discover that much of this roughness was the result of art, being assumed with the view of extorting by terror a ready compliance with his commands."

Prior to his embarkation from La Rochelle Humbert had difficulties of no trifling nature to contend with. As stated, France's resources had been sorely taxed by the expedition to Egypt, and neither money nor even necessaries for the troops could be obtained from the Commissariat Department. Yet no obstacle could daunt the indomitable spirit of the soldier. Hoche was no more, but the same determination to strike a blow at England's vital point controlled the actions of his friend and successor. Impatient of delay, and refusing longer to await the coöperation of others, Humbert and his slender detachment put to sea on the morning of August 4th, at seven o'clock. The event occasioned much enthusiasm in La Rochelle, and the quays were thronged with citizens who shouted themselves hoarse in bidding god-speed to the "Army of Ireland." A powerful English fleet was cruising within a mile of the port, and it required great skill on the part of Division Commander Daniel Savary to escape a conflict. Only by plying vigorously to the windward did he succeed. It had been decided in advance that rather than accept battle against the tremendous odds the three vessels should be run aground on the Spanish coast.(10)

Humbert's armament consisted of three frigates: the Concorde and Medée, of 44 eighteen-pounders each, and the Franchise, of 38 twelve-pounders. His entire landing strength did not exceed 1,060 rank and file and 70 officers, with two pieces of field artillery, four-pounders. He also brought 5,500 stands of arms for the arming of the Irish peasantry.(11) His troops were composed in the main of infantry of the line, with two companies of grenadiers and a squadron of the Third Regiment of Chasseurs. All were veterans and had seen service under Jourdan and Moreau on the Rhine, or under Bonaparte in Italy.

The officers, some of whom bore on their persons the marks of many a bloody encounter, deserve a preliminary notice. There was Sarrazin, to begin with, a remarkable figure in his way, whose career, like Humbert's, may be considered thoroughly illustrative of the peculiar conditions created in the military system of France by the change in her political life. Born in 1770, the third year of the revolution already saw him a captain of infantry. In 1794 he was transferred to the Engineers, but shortly after, in consequence of prowess in the field, received his commission as colonel of the Fourteenth Regiment of Dragoons. In 1796 he was already a general-adjutant, and, as will soon be shown, the "Irish Campaign" brought him further promotion. Sarrazin, in other words, was the true type of the French Republican soldier: a product of those troublesome and stormy times when success meant rapid rise to honors and distinctions, and failure—the gory embrace of the guillotine!(12)

GENERAL SARRAZIN

Next in authority after Sarrazin came Adjutant-General Louis Octave Fontaine, to whose pen the author is indebted for a remarkable account of the expedition. His book, or pamphlet, was published in Paris two years after the event, and although it teems with errors, geographical, chronological and others, it is valuable as the only authentic French version in existence, outside of General Humbert's meagre reports to the Directory. The writer constantly refers to himself in the third person as "le brave Général Fontaine," and would have us believe that the partial success of the invasion was due to his own foresight and energy. With a naiveté refreshing for its very frankness, he places himself in the light of a Deus ex machina, ever turning up at the right moment to extricate his companions from dire dilemmas and show them the road to victory. This naiveté attains its pinnacle when, as if by an after-thought, he explains at the conclusion of his work that he has purposely omitted mentioning the names of his companions-in-arms for fear of overlooking any one of them and thus causing unmerited pain. The fatuous vanity of the writer, and his unfortunate habit of treating Irish names and places as unworthy of proper record, does not prevent his furnishing many a missing link to the chain of evidence touching this extraordinary phase of modern history, and for so much, if for no other reason, posterity must feel grateful to him.

Several Irishmen accompanied Humbert in various capacities. Bartholomew Teeling, of Lisburn, was one. He was a young man who had left his native country—a mere stripling—to join the French Republican Army. He had fought side by side with rabid atheists and open enemies of the Church, and yet through all these experiences his faith in the religion of his forefathers had never slackened. A scholar, a patriot and an observer, with an admixture of the enthusiast, he had not allowed his political convictions to interfere with his religious belief. His mildness of manner and patrician bearing formed a pleasing contrast to the rough, soldier-like deportment of Humbert, who had selected him as his aide-de-camp. Humbert's official interpreter was another Irishman, one Henry O'Keon, the son of a cow-herd of Lord Tyrawley. He was born in the neighborhood of Kilcummin, the landing-place of the French near Killala—a circumstance which points its own conclusion and refutes the oft-repeated statement that that spot had been selected by mere chance. Having learned a little Latin at school, O'Keon repaired to Nantes, Brittany, where he studied theology and received holy orders. On the advent of the republic he suddenly changed his convictions—if indeed he had ever entertained any—enlisted in the army as a private, and was gradually advanced to the rank of major. He was physically well developed and possessed the heavy, coarse features of the lower type of the Celtic race. The merry twinkle of his eyes and the joviality of his ruddy countenance completely dispelled the repellent effect of a pair of heavy, beetling eyebrows. He spoke Irish and French fluently, and English indifferently. His part in the campaign was a creditable one, and would entitle him to an honorable place in its history had he not marred it by an act of dishonesty toward the Bishop of Killala, and a breach of good morals, before his final departure for France.(13)

Two other Irishmen accompanied the expedition—Matthew Tone, already mentioned, brother of the celebrated Theobald Wolfe Tone, and one O'Sullivan, a native of South Ireland and one of the very few rebel leaders who were fortunate enough to escape the avenging hand of the British Government. Although captured by the loyalists, he was not recognized, and afterward made his way back to the continent.