The Battle of Ballina

The Field of Operations—Morale of the English Forces—An Engagement near Ballina—Episodes at the Capture of that Town

AVING stated the situation of the invading force, let us glance at the field of operations and the dispositions for defence made by the British military authorities At the conclusion of the first chapter allusion was made to the rebellious outbreaks in counties Wexford and Wicklow and the province of Ulster, during May and June, 1798 and their bloody suppression by the troops of the king. These different disturbances had resulted in the concentration in various portions of the unfortunate country of bodies of regulars and militia aggregating 150,000 men, under the supreme command of Lord Cornwallis, the brave opponent of Washington. The regulars constituted the flower of the English Army, and before landing in Ireland had seen service in the Netherlands, in India and elsewhere. The militia or yeomanry consisted of volunteers recruited from the body of the Protestant population of the country—descendants of the earlier English and Scotch invaders and settlers. The corps came into existence in the autumn of 1796, at the instance of the government, which, foreseeing the evil consequences likely to ensue from the prevailing abuses, desired to build up a solid dam against the inflowing tide of popular indignation. In the teeth of Catholic opposition a measure passed the Irish Parliament creating a force of 20,000 men, and this number swelled to 36,000 before the end of the first six months. During the rebellion the yeomanry force exceeded 50,000 men of all arms.

MARQUIS OF CORNWALLIS

With regard to the discipline and moral standing of the army as a whole, it is sufficient to quote the opinion of Sir Ralph Abercromby, who, after short service, retired from its command as involving, in his opinion, duties unworthy of a soldier. On February 26, 1798, this gallant officer, in an official report, declared that he had found the force "in such a state of licentiousness that must render it formidable to every one but the enemy!" Of the yeomanry in particular Lord Cornwallis, on July 8th, or less than three weeks after his appointment to the lord-lieutenancy of Ireland, wrote the following scathing denunciation to Lord Portland:

"The Irish militia are totally without discipline; contemptible before the enemy when serious resistance is made to them, but ferocious and cruel in the extreme when any poor wretches, either with or without arms, come within their power; in short, murder appears to be their favorite pastime." Writing to General Ross, the lord-lieutenant furthermore declared that England was engaged "in a war of plunder and massacre;" and, after referring to court-martial executions, continued: "But all this is trifling compared to the numberless murders that are hourly committed by our people without any process of examination whatever."

No comments of the historian, however unbiassed he be, can carry the weight that attaches to these statements of the two most chivalrous British officers of the day.

The first English commander to receive intelligence of the French landing at Killala was Major-General John Hely Hutchinson, stationed with a large force in the town of Galway. Without awaiting instructions from his superior, the Marquis of Cornwallis, he resolved to march northward with all his available troops, leaving the southern section to take care of itself as best it could, both against a possible rebellion or another French descent. His corps was composed of the Kerry militia, recruited in Galway, some Kilkenny yeomanry from Loughrea, a body of Longford militia from Gort, a detachment of so-called Royal Roxburgh Fencible Dragoons under the command of Lord Roden, several companies of a Highland regiment known as the Fraser Fencibles, and four six-pounders and a howitzer served by men of the Royal Irish Artillery.

Almost simultaneously with this movement of troops from the south occurred a still more formidable one from the west. Lord Cornwallis was apprised of the invasion on the 24th of August. With his usual energy he took immediate measures to meet the emergency, and as a preliminary step despatched General Gerard Lake to the town of Galway to conduct the operations commenced from that point. Then, collecting as many troops as could be spared in the east, he started in person for Connaught. He arrived at Phillipstown on the 26th with the One Hundredth Regiment Royal Infantry, the First and Second of Light Infantry, and the flank companies of the Buck and Warwick militia. Two days later the army had already reached the village of Kilbeggan, forty-four miles further west—a fact that speaks well for the endurance of the troops and the resolution of their commander.

Having completed his arrangements for an offensive movement, Humbert, on the other hand, on the morning of August 24th left Killala with the major portion of his army—if, indeed, his handful of men may be dignified by this term—and struck for the south. His primary object was to drive the enemy from Ballina, after which he intended marching on to Castlebar, the county town of Mayo, where he had learned that a concentration of troops was contemplated. He hoped by a march into the interior to enlist every Catholic in the cause of Irish liberty, and thus add to his feeble strength; for, to tell the truth, the results of the two first days' recruiting had been a bitter disappointment to him. A goodly proportion of the raw levies, after realizing that their deliverers were thoroughly determined to prevent the plundering of the Protestants, had simply dropped out of the ranks and settled down at a safe distance to await developments.

Before long the vanguard of the French force espied the British troops posted in an advantageous position a few miles north of Ballina. Major Kerr had received considerable reëforcements, including some veteran cavalry, and had boldly pressed forward to encounter the foe. As on the two previous occasions, Sarrazin led the attack of the French. His detachment consisted of the grenadiers—about two hundred picked men—and one battalion of the line. Dismounting from his horse, he placed himself at the head of the foremost column, and with a theatrical gesture, calculated to impress his men—French soldiers have ever been impressed by trifles—ordered the advance at double-quick. "à la baionette" was his battle-cry, and it reechoed all along the line; and the blue-coated troopers sprang with their wonted agility over the broken ground and throw themselves against the front ranks of the enemy with an irresistible élan. Still, Major Kerr was not unprepared for the attack, and the rapid but regular platoon firing of the yeomanry and carabineers might have proved an effectual check even to the veteran grenadiers had not General-Adjutant Fontaine turned the flank of the British position, and poured in his volleys almost on their rear. Seeing himself in danger of being surrounded, Major Kerr sounded the retreat, which became a disorderly rout when Humbert appeared in person with a detachment of the third regiment of Chasseurs mounted on horses obtained in Killala.(19)

The town of Ballina presented a scene of unutterable confusion when the defeated troops arrived there, all begrimed and gory. The inhabitants of both persuasions sought refuge in their homes, the Catholics from fear of the fugitives, the Protestants from fear of the French. One luckless individual by the name of Walsh, who had previously been arrested on suspicion of disloyalty, but discharged for lack of evidence, was caught in the act of inciting his fellow-citizens to rebellion. Brought before Major Kerr, a commission was found in his pockets, signed by Humbert, authorizing him to gather recruits for the Irish Republic. Without a trial of any kind he was taken to a crane in the marketplace and unceremoniously strung up amid the hooting of the soldateska and the piteous appeals of his friends.(20) This was the first of a long series of acts of reprisal committed by the king's troops on the unfortunate rebels of Connaught. It was no new pastime to the former. Their hands had already been deeply steeped in the blood of Irish insurgents in Wexford, Ulster and elsewhere. They had grown callous to the dictates of humanity.

The immediate consequences of the second engagement north of Ballina were the evacuation of this town by the royal troops, and the accession to the French ranks of another small corps of Irish recruits. Humbert's field force thus amounted to something over 800 Frenchmen and 1,000 or 1,500 native auxiliaries. The balance of the invading army, numbering 200 rank and file and five officers, under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Charost, had been left in Killala for different reasons. They were needed there to guard a large quantity of ammunition landed by the squadron the day preceding its departure for France,(21) and also to assure the safety of the Protestant population, daily threatened by the more desperate of the United Irishmen. Further, it was feared that an English force from Sligo might attempt a landing at Killala for the purpose of cutting off Humbert's communications, unless the town were adequately protected by a disciplined body of troops. Humbert did not resume his march until the 25th. At three o'clock in the afternoon he moved toward the village of Rappa,(22) and remained there until two in the morning, the delay being caused principally by the difficulties in dealing with his new allies, who, as previously stated, lacked every kind of military training.

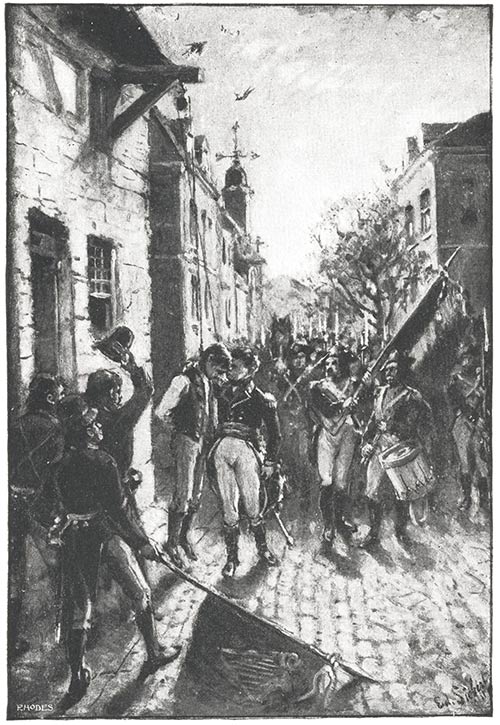

Sarrazin in the mean time had followed close upon the heels of the retreating British. On the afternoon of the skirmish with Kerr, with drawn sabre, at the head of his grenadiers and chasseurs, he entered the deserted streets of Ballina. As they neared the market square the outlines of a suspended figure became discernible against the white background of a whitewashed building. It was the body of the unfortunate Walsh. When the entire column came up and the identity of the dead man was established, Sarrazin, by a happy inspiration, stepped up to the crane, threw his arms around the inanimate form, and imprinted a kiss on the livid brow. "Voilà, Messieurs," he cried, turning to the Irish auxiliaries, "thus do we honor the martyrs of your sacred cause." Major O'Keon translated the words into the native vernacular, and the assemblage, now swelled by two-thirds of the town's inhabitants, joined in a deafening shout of applause. Each company, in passing the swaying body, dipped its colors and presented arms, and, each in his turn, the different commanders stepped up to the corpse and gave it the embrace of "sympathetic civism." Had the entire comedy been prearranged instead of being a clever impromptu, it could not have passed off more propitiously, or made so deep an impression on the spectators.

"Sarrazin, by a happy inspiration, stepped up to the crane, threw his arms around the inanimate form, and imprinted a kiss on the livid brow."—Page 69.

The experiences of the last few days had taught the French that the deeply rooted religious sentiments of the native Irish must be respected, and with that faculty for adapting themselves to circumstances which seems to be inherent in the Gaul, the invaders decided to turn these very sentiments to the best possible account. Accordingly, after indulging in the little scene just described, Sarrazin ordered Walsh's body to be cut down and carried to the nearest Romish chapel. Here it was attired in a French military suit, placed in a handsome coffin and laid out in state, surrounded by burning tapers and mourners with crucifixes and censers. And all this to the tune of the "Marseillaise" and "Ça Ira," and the sacriligious jests—fortunately not understood by those at whom they were directed—of the French Republican soldiery!

The French did not stop here in their efforts to conciliate the Catholic element. They were playing a desperate game, and appreciating that everything was at stake, they hesitated at no measure, short of compliance with the demanded persecution of the Protestants, that would insure the most efficient aid from that source. Acting under instructions from the commander-in-chief, O'Keon mounted a rostrum in the market-place of Ballina and told the assembled throng the following interesting story in Irish: He dreamt one night, he said, that the Holy Mother of God visited his bedside and poured into his ear the story of Ireland's suffering and woe.

This done, she called upon him to arise, return home, and battle in the cause of Irish freedom. The speaker declared that he at first regarded the apparition as an idle dream, unworthy of serious consideration; but a few nights later the visit was repeated. This time she bemoaned in still more melancholic accents the condition of his mother country, and urged him once more to return home. Still taking no notice of the warning, the speaker received a third visit, his heavenly guest making herself felt, as well as heard, by administering a sharp box on his ear. Convinced by this manifestation that the Madonna's order was seriously meant, O'Keon repaired to the French Directory and persuaded them to undertake this expedition! He assured his hearers that the success of the enterprise must be a foregone conclusion, as the Holy Mother had herself advised it and would never abandon her faithful followers.(23) O'Keon's harangue was received with every demonstration of delight by the impressionable peasantry, not one of whom appeared to doubt a single word of it.

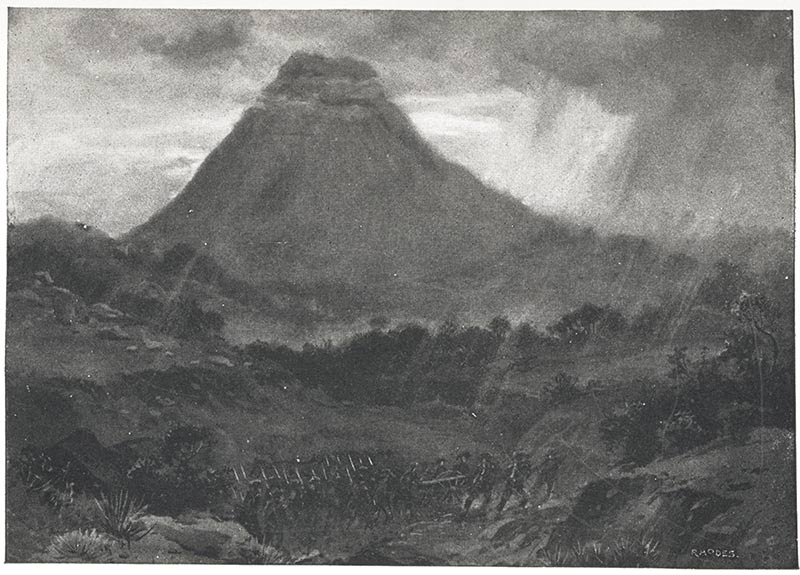

Humbert entered Ballina early on Sunday, the 26th, with the main body, but his stay there was very short. Peasants came in during the morning with the information that the enemy's forces at Castlebar were hourly increasing. General Hutchinson had arrived there, they said, with his Galway division, and reëforcements were constantly joining him.(24) This was, therefore, no time for dillydallying. After a few hours' rest the French general, with his entire corps, moved out of Ballina toward the capital of Mayo. It was three o'clock in the afternoon, and threatening clouds were gathering on the horizon. The heavens, the landscape, and the prospects of the marching hundreds seemed equally gloomy.

"The heavens, the landscape, and the prospects of the marching hundreds, seemed equally gloomy."—Page 72.