The Haunted Cellar - Fairy Legends of Ireland

HERE are few people who have not heard of the Mac Carthies, one of the real old Irish families, with the true Milesian blood running in their veins as thick as buttermilk. Many were the clans of this family in the south; as the Mac Carthy-more, and the Mac Carthy-reagh, and the Mac Carthy of Muskerry; and all of them were noted for their hospitality to strangers, gentle and simple.

But not one of that name, or of any other, exceeded Justin Mac Carthy, of Ballinacarthy, at putting plenty to eat and drink upon his table; and there was a right hearty welcome for every one who should share it with him. Many a wine-cellar would be ashamed of the name if that at Ballinacarthy was the proper pattern for one. Large as that cellar was, it was crowded with bins of wine, and long rows of pipes, and hogsheads and casks, that it would take more time to count than any sober man could spare in such a place, with plenty to drink about him, and a hearty welcome to do so.

There are many, no doubt, who will think that the butler would have little to complain of in such a house; and the whole country round would have agreed with them, if a man could be found to remain as Mr. Mac Carthy's butler for any length of time worth speaking of; yet not one who had been in his service gave him a bad word.

"We have no fault," they would say, "to find with the master, and if he could but get any one to fetch his wine from the cellar, we might every one of us have grown grey in the house, and lived quiet and contented enough in his service until the end of our days."

"'Tis a queer thing that, surely," thought young Jack Leary, a lad who had been brought up from a mere child in the stables of Ballinacarthy to assist in taking care of the horses, and had occasionally lent a hand in the butler's pantry: "'Tis a mighty queer thing, surely, that one man after another cannot content himself with the best place in the house of a good master, but that every one of them must quit, all through the means, as they say, of the wine-cellar. If the master, long life to him, would but make me his butler, I warrant never the word more would be heard of grumbling at his bidding to go to the wine-cellar."

Young Leary accordingly watched for what he conceived to be a favourable opportunity of presenting himself to the notice of his master.

A few mornings after, Mr. Mac Carthy went into his stable-yard rather earlier than usual, and called loudly for the groom to saddle his horse, as he intended going out with the hounds. But there was no groom to answer, and young Jack Leary led Rainbow out of the stable.

"Where is William?" inquired Mr. Mac Carthy.

"Sir?" said Jack; and Mr. Mac Carthy repeated the question.

"Is it William, please your honour?" returned Jack; "why, then, to tell the truth, he had just one drop too much last night."

"Where did he get it?" said Mr. Mac Carthy; for since Thomas went away the key of the wine-cellar has been in my pocket, and I have been obliged to fetch what was drunk myself."

"Sorrow a know I know," said Leary, "unless the cook might have given him the laste taste in life of whiskey. But," continued he, performing a low bow by seizing with his right hand a lock of hair and pulling down his head by it, whilst his left leg, which had been put forward, was scraped back against the ground, "may I make so bold as just to ask your honour one question?"

"Speak out, Jack," said Mr. Mac Carthy.

"Why, then, does your honour want a butler?"

"Can you recommend me one," returned his master, with the smile of good-humour upon his countenance, "and one who will not be afraid of going to my wine-cellar?"

"Is the wine-cellar all the matter?" said young Leary; "devil a doubt I have of myself then for that."

"So you mean to offer me your services in the capacity of butler?" said Mr. Mac Carthy, with some surprise.

"Exactly so," answered Leary, now for the first time looking up from the ground.

"Well, I believe you to be a good lad, and have no objection to give you a trial."

"Long may your honour reign over us, and the Lord spare you to us!" ejaculated Leary, with another national bow, as his master rode off; and he continued for some time to gaze after him with a vacant stare, which slowly and gradually assumed a look of importance.

"Jack Leary," said he, at length, "Jack—is it Jack?" in a tone of wonder; "faith, 'tis not Jack now, but Mr. John, the butler;" and with an air of becoming consequence he strode out of the stable-yard towards the kitchen.

It is of little purport to my story, although it may afford an instructive lesson to the reader, to depict the sudden transition of nobody into somebody. Jack's former stable companion, a poor superannuated hound named Bran, who had been accustomed to receive many an affectionate pat on the head, was spurned from him with a kick and an "Out of the way, sirrah." Indeed, poor Jack's memory seemed sadly affected by this sudden change of situation. What established the point beyond all doubt was his almost forgetting the pretty face of Peggy, the kitchen wench, whose heart he had assailed but the preceding week by the offer of purchasing a gold ring for the fourth finger of her right hand, and a lusty imprint of good-will upon her lips.

When Mr. Mac Carthy returned from hunting, he sent for Jack Leary—so he still continued to call his new butler. "Jack," said he, "I believe you are a trustworthy lad, and here are the keys of my cellar. I have asked the gentlemen with whom I hunted today to dine with me, and I hope they may be satisfied at the way in which you will wait on them at table; but, above all, let there be no want of wine after dinner."

Mr. John, having a tolerably quick eye for such things, and being naturally a handy lad, spread his cloth accordingly, laid his plates and knives and forks in the same manner he had seen his predecessors in office perform these mysteries, and really, for the first time, got through attendance on dinner very well.

It must not be forgotten, however, that it was at the house of an Irish country squire, who was entertaining a company of booted and spurred fox-hunters, not very particular about what are considered matters of infinite importance under other circumstances and in other societies.

For instance, few of Mr. Mac Carthy's guests (though all excellent and worthy men in their way) cared much whether the punch produced after soup was made of Jamaica or Antigua rum; some even would not have been inclined to question the correctness of good old Irish whiskey; and, with the exception of their liberal host himself, every one in company preferred the port which Mr. Mac Carthy put on his table to the less ardent flavour of claret, a choice rather at variance with modern sentiment.

It was waxing near midnight when Mr. Mac Carthy rung the bell three times. This was a signal for more wine; and Jack proceeded to the cellar to procure a fresh supply, but it must be confessed not without some little hesitation.

The luxury of ice was then unknown in the south of Ireland; but the superiority of cool wine had been acknowledged by all men of sound judgment and true taste.

The grandfather of Mr. Mac Carthy, who had built the mansion of Ballinacarthy upon the site of an old castle which had belonged to his ancestors, was fully aware of this important fact; and in the construction of his magnificent wine-cellar had availed himself of a deep vault, excavated out of the solid rock in former times as a place of retreat and security. The descent to this vault was by a flight of steep stone stairs, and here and there in the wall were narrow passages—I ought rather to call them crevices; and also certain projections, which cast deep shadows, and looked very frightful when any one went down the cellar-stairs with a single light; indeed, two lights did not much improve the matter, for though the breadth of the shadow became less, the narrow crevices remained as dark and darker than ever.

Summoning up all his resolution, down went the new butler, bearing in his right hand a lantern and the key of the cellar, and in his left a basket, wnich he considered sufficiently capacious to contain an adequate stock for the remainder of the evening: he arrived at the door without any interruption whatever; but when he put the key, which was of an ancient and clumsy kind—for it was before the days of Bramah's patent,—and turned it in the lock, he thought he heard a strange kind of laughing within the cellar, to which some empty bottles that stood upon the floor outside vibrated so violently that they struck against each other: in this he could not be mistaken, although he may have been deceived in the laugh, for the bottles were just at his feet, and he saw them in motion.

Leary paused for a moment, and looked about him with becoming caution. He then boldly seized the handle of the key, and turned it with all his strength in the lock, as if he doubted his own power of doing so; and the door flew open with a most tremendous crash, that if the house had not been built upon the solid rock would have shook it from the foundation.

To recount what the poor fellow saw would be impossible, for he seems not to have known very clearly himself: but what he told the cook next morning was, that he heard a roaring and bellowing like a mad bull, and that all the pipes and hogsheads and casks in the cellar went rocking backwards and forwards with so much force that he thought everyone would have been staved in, and that he should have been drowned or smothered in wine.

When Leary recovered he made his way back as well as he could to the dining-room, where he found his master and the company very impatient for his return.

"What kept you?" said Mr. Mac Carthy in an angry voice; "and where is the wine? I rung for it half an hour since."

"The wine is in the cellar, I hope, sir," said Jack, trembling violently; "I hope 'tis not all lost."

"What do you mean, fool?" exclaimed Mr. Mac Carthy in a still more angry tone: "why did you not fetch some with you?"

Jack looked wildly about him, and only uttered a deep groan.

"Gentlemen," said Mr. Mac Carthy to his guests, "this is too much. When I next see you to dinner I hope it will be in another house, for it is impossible I can remain longer in this, where a man has no command over his own wine-cellar, and cannot get a butler to do his duty. I have long thought of moving from Ballinacarthy; and I am now determined, with the blessing of God, to leave it tomorrow. But wine you shall have were I to go myself to the cellar for it." So saying, he rose from table, took the key and lantern from his half-stupefied servant, who regarded him with a look of vacancy, and descended the narrow stairs, already described, which led to his cellar.

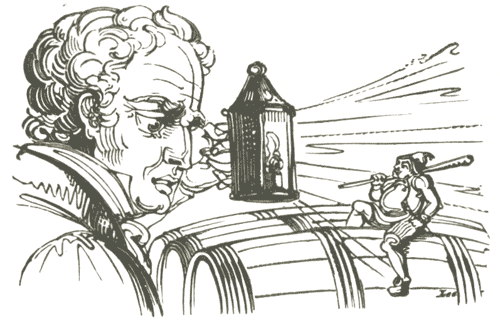

When he arrived at the door, which he found open, he thought he heard a noise, as if of rats or mice scrambling over the casks, and on advancing perceived a little figure, about six inches in height, seated astride upon a pipe of the oldest port in the place, and bearing a spigot upon his shoulder. Raising the lantern, Mr. Mac Carthy contemplated the little fellow with wonder: he wore a red nightcap on his head; before him was a short leather apron, which now, from his attitude, fell rather on one side; and he had stockings of a light blue colour, so long as nearly to cover the entire of his leg; with shoes, having huge silver buckles in them, and with high heels (perhaps out of vanity to make him appear taller). His face was like a withered winter apple; and his nose, which was of a bright crimson colour, about the tip wore a delicate purple bloom, like that of a plum; yet his eyes twinkled

———"like those mites

Of candied dew in moony nights—"

and his mouth twitched up at one side with an arch grin.

"Ha, scoundrel!" exclaimed Mr. Mac Carthy, "have I found you at last? disturber of my cellar—what are you doing there?"

"Sure, and master," returned the little fellow, looking up at him with one eye, and with the other throwing a sly glance towards the spigot on his shoulder, "a'n't we going to move to-morrow? and sure you would not leave your own little Cluricaune Naggeneen behind you?"

"Oh!" thought Mr. Mac Carthy, "if you are to follow me, Mister Naggeneen, I don't see much use in quitting Ballinacarthy." So filling With wine the basket which young Leary in his fright had left behind him, and locking the cellar door, he rejoined his guests.

For some years after Mr. Mac Carthy had always to fetch the wine for his table himself, as the little Cluricaune Naggeneen seemed to feel a personal respect towards him. Notwithstanding the labour of these journeys the worthy lord of Ballinacarthy lived in his paternal mansion to a good round age, and was famous to the last for the excellence of his wine and the conviviality of his company; but at the time of his death that same conviviality had nearly emptied his wine-cellar; and as it was never so well filled again, nor so often visited, the revels of Master Naggeneen became less celebrated, and are now only spoken of amongst the legendary lore of the country. It is even said that the poor little fellow took the declension of the cellar so to heart that he became negligent and careless of himself, and that he had been sometimes seen going about with hardly a skreed (rag) to cover him.