DUNSEVERICK CASTLE.

From the Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 46, May 11, 1833

The following description of this castle, has been sent us by our esteemed contributor, Mr. S. M'Skimin, author of the History and Antiquities of Carrickfergus.

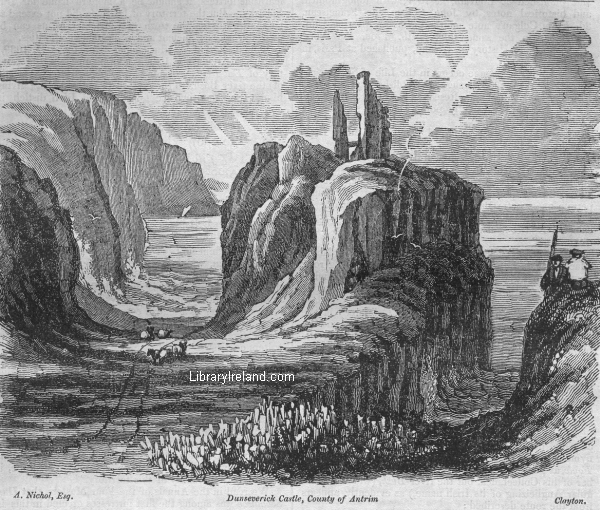

"On an insulated rock, near the centre of a small bay, three miles east of the Giant's Causeway, stand the ruins of the Castle of Dunseverick, formerly the seat of a branch of the ancient family of O'Cahan, or as they were commonly called by the English and Scottish settlers, O'Kane. Traces of the outworks of this building are visible around the rock on which it stands, while its shattered keep appeals to 'nod o'er its own decay,' and is destined at no distant period to become as prostrate as other fragments of the ruins scattered about. Immense masses of the rock have been hewn away, evidently for the purpose of rendering the castle as inaccessible as possible; an enormous basaltic rock, south of the entrance, also appears to have been cut into a pyramidical form, and flattened on the top, perhaps as a station for a warder, or for the purpose of placing it upon some engine of defence."

That this is the remotely ancient and celebrated Dun-Sovarke, of ancient Irish history, we shall make appear, in direct opposition to all the Irish writers of this and the last century, one only excepted.

Charles O'Conor, of Belanagare, in his map of Ireland, called Scotia Antiqua, or a Map of Ireland agreeable to the days of Ptolemy, makes Dunsobarky the present Carrickfergus, and he has been followed by Beauford, in the 11th number of Vallancey's Collectanea--by Dubourdieu in his Statistical Account of the County of Antrim--by the ingenious William Haliday, of Dublin, in a map prefixed to his translation of the first part of Keating's History of Ireland--and by our worthy correspondent, Mr. M'Skimin, who in his Antiquities of Carrickfergus, takes it for granted that Beauford's ridiculous derivation of the name of this place is correct. Archdall, in a manuscript compiled by him, styled, "Hiberniae Antiquae et novae Nomenclatura," is still farther from the truth, when he asserts that Dunsobhairce is the present Downpatrick.

But Dun Sobhairce was never stated to be Carrickfergus, before the time of Charles O'Conor, of Belanagare, who published his Dissertations on the History of Ireland, in the year 1753. Besides, there is no evidence that Carrickfergus was ever called by any other than its present name; and it is also manifest, that O'Conor was but very imperfectly acquainted with the topography of the County of Antrim, from the fact that, on his map called Ortelius Improved, he has placed Dunluce several miles out of its proper locality, and given it an inland situation. Dunseverick, or Dunseverig is evidently an Anglicizing of its Irish name, Dun Sobhairgi, or, as it is called in the Book of Armagh, Duin Sebuirgi, which is pronounced Doon Severgi, and this alone should be considered a strong presumptive proof of their being the same: but as mere agreement of names might not probably satisfy stern enquirers after truth, we shall demonstrate our position from authorities whose title to topographical credit will not for a moment be disputed by those who are capable of appreciating the value of historic monuments.

1st. From the Book of Armagh, an undoubted MS. of the seventh century. 2d. From the Tripartite Life of St. Patrick, a very ancient MS., translated into Latin, and published at Louvain, in 1647, with topographical and historical notes, by John Colgan, the Franciscan. 3d. From Colgan's note on the passage respecting Dunsobhairce, in the same Life. 4th. From the Abbe M'Geoghegan's History of Ireland, published at Paris, in 1758.

The following passage occurs in the Life of St. Patrick, given in the Book of Armagh, as published by Sir William Betham, Antiquarian Researches, Vol. II. Appendix, pp. 34, 35, which distinctly points out the situation of Dun Sobhairce.

"Evenit (Patricius) in Ardd Stratho et Mac Ercae episcopum ordinavit, et exiit in Ard Eolerg et Ailgi et Lee Bendrigi, & perrexit trans flumen Bandae et benedixit locum in quo est Cellola Cuile Raithin in Eilniu in quo fuit episcopus, et fecit alias Cellas multas in Eilniu. Et per Buas foramen pertulit, et in Duin Sebuirgi sedit super petram quam petra Patricii usque nunc, et ordinavit ibi Olcanum sanctum episcopum, &c., et reversus est in campum Elni et fecit reliquas multas ecclesias quas Coindiri habent."

"He (St. Patrick) came to Ardstrath, and ordained Mac Ercae bishop, and departed to Ard Eolerg, (a rock over Lough Foyle,) and to Ailgi, (i. e. Ailigh, six miles north-west of Derry,) and to Lee-Bendrigi, (now Coleraine barony,) and crossed the river Bann, and blessed the place where is the little cell of Cuil Raithin (Coleraine) in the plain of Eilniu, in which there was a bishop; and he erected many other cells (i. e. kills, or churches) in the plain of Eilniu, and he crossed the BUAS, (undoubtedly the river Bush,) and at DUIN SEBUIRGI sat upon a rock, which is called St. Patrick's rock to this day, and there he consecrated holy Olcan bishop, whom he himself had educated, and he returned into the plain of Eilne, and erected many other churches, which the Coindiri, (inhabitants of diocese of Connor,) possess."

This clearly shows that the Buas is not the river Lagan, as stated by O'Flaherty, O'Conor, Archdall, and the anonymous author of the History of Belfast; much less the Foyle, as positively asserted by Vallancey in the 12th number of his Collectanea, but the river Bush, (which is a regular Anglicizing of its Irish name,) as evidently appears from the route described:

"He crossed the Bann, blessed Coleraine, and moving onwards (i. e. eastwards,) crossed the Buas." This passage also shows that Dun Sebuirgi could not be Carrickfergus; for after his crossing the Bush, he is said to have proceeded directly to Dun Sebuirgi; but it agrees exactly with the situation of Dunseverick, which lies a short distance east of that river.

The situation of Dun Sobhairce, is more distinctly pointed out in the Tripartite Life of St. Patrick, Lib. II. cap. 130. It is there placed in the territory of Cathrigia, which we could demonstrate to be the present barony of Carey, in the county of Antrim, did the limits of this little Journal permit us to enter into long disquisitions upon places and names. We must therefore hope that our own veracity in stating facts, will be depended upon, although it must be acknowledged that the sincerest enquirers after truth frequently labour under a fond delusion.

Colgan's note upon this passage is so satisfactory as to the situation of Dun Sobhairce, that we consider it worth giving at full length.

"Dun Sobhairce est arx maritima et longe vetusta regionis Dal Riediae, quae nomen illud a Sobarchio filio Ebrici, Rege Hiberniae primoque arcis illius conditore circa annum mundi 3668, desumpsit, ut ex Quatuor Magistris in Annalibus, Catalogo Regum Hiberniae Ketenno, Lib. I., et aliis passim rerum Hibernicarum Scriptoribus colligitur."-- Triad. Thaum. p. 182, col. b note 205.

"Dun Sobhairce is a maritime and remotely ancient fortress of the territory of Dalriada, which derived that name from Sobhairci, the son of Ebric, the FIRST founder of that fortress, about the year of the world 3668, as may be learned from the Four Masters in their Annals--from Keating-, in his Catalogue of the Kings of Ireland--and from other writers of Irish history."

Charles O'Conor, not knowing the extent of the territory of Dalriada, conjectured that as Carrickfergus was a maritime fortress, it should be a modern name for Dun Sobarky. But the territory of Dalriada did not extend so far southwards as the town of Carrickfergus, as can be proved from very ancient and respectable authorities.

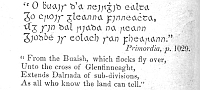

Randal, Earl of Antrim, (nuper defunctus A.D. 1639,) writing to Archbishop Usher, informs him that the territory of Dal Riada extended thirty miles from (the mouth of) the river Bush, to the cross of Glandfinneaght; giving him at the same time the following old Irish distich, in confirmation of it:--

The Glenfinneaght here mentioned, is the present village of Glynn, which is, in a direct line, thirty Irish miles from the mouth of the river Bush; and the valley in which the old church of Glynn is situated, formed a part of the southern boundary of the territory of Dal-riada. It follows, therefore, as a logical consequence, that Duin-Sobhairce, a maritime fortress of Dal-Riada, could not be Carrickfergus, as too hastily presumed by many modern writers on Irish antiquities.

The Abbe Ma-Geoghegan, who published his History of Ireland, in Paris, in the year 1758, was well acquainted with the situation of this ancient fortress:--

"I'l (S. Patrice) s'avanca ensuite par la contree de Dalrieda, anjourdhui Route, au comte de Antrim, jusqu au chateau de Dun-Sobhairche, dans le extremite septentrionale de cette contree."--Tom. I. p. 225.

"He (St. Patrick) afterwards proceeded through the territory of Dalriada, at present called Route, in the county of Antrim, as far as the castle of Dun Sobhairche, in the northern extremity of this territory."

We read in the Annals of the Four Masters, that Dun-Sobhairce was among the first fortresses erected in this island by the Milesians:--

A. M. 3501. "This is the year in which Heremon and Heber assumed the joint government of Ireland, and divided Ireland equally between them. In it also the following fortresses, &c. were erected, viz. Rath-beathaigh, on the banks of the river Nore, in Argatros, (now Rathveagh, within five miles of Kilkenny; (Rath-oin, in the territory of Cualann, (now the County Wicklow;) the causeway of Inbhear-mor, (now Arklow;) the house in Dun-nair. on the Mourne mountains. Dun-Delginnis, in the territory of Cualann, (now Delgany, Co. Wicklow;) DUN SOBHAIRCE, in Murbholg of Dalriada, (Dunseveric,) was erected by Sovarke; and Dun Edair, (on the Hill of Howth,) by Suighde; all these foregoing were erected by Heremon and his Chieftains. Rath-Uamhain, in Leinster; Rath-arda, Suird, (Swords;) Carrac Fethen, Carrac Blarne, (Blarney,) Dun-aird Inne, Rath Riogbhard, in Murresk, were erected by Heber and his chieftains."

We read in the Book of Ballymote, folio 87, p. a, col. a, line 10, and in the Book of Lecan, folio 123, p. a, col. a, line 10. "That this Sobhairce and his brother Cearmna, assumed the joint government of Ireland; the former residing at Dun Sobhairce, in the north, and the latter at Dun-Cearmna, in the south. Sobhairce was afterwards slain within this fortress, by Eochaidh Echchenn, King of the Fomorians, or sea pirates.

"A. M. 4176. Rotheacht having been seven years king of Ireland, was burned by lightning in Dunsobhairce. It was by this Rotheacht that chariots of four horses were first established in Ireland." -- Annals of the Four Masters.

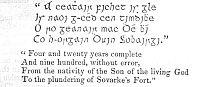

No other notice of this fortress occurs in our annals until the year 994, in which it is stated that it was plundered by the Danes; and so important was the place at that time that an Irish Rann was composed, to hand down the date of its ransacking.

"A. D. 924. Dun Sobhairce was plundered by the Danes of Loch Cuan (Strangford Lake in the county Down), and they slew many persons on this occasion.

In latter times we find this castle in the possession of the M'Quillans, or, as the Irish writers call them, Mac Uidhlin, a family that arrived in Ireland among the first English adventurers. Duald M'Firbis says, in his account of English and Irish families, that Mac Uidhlin was descended from an Irish chieftain of the Dalriadan tribe, who emigrated to Wales at an early period, and whose posterity remained there, until some of them returned at the period of the English invasion; and those Iberno-Welshmen, knowing from tradition that they were of the Dalriadan stock, settled in the territory of their ancestors. Whether this be true or false, I dare not venture to assert, but the Annals of the Four Masters, which are full of the exploits of the Mac Uidhlins, never speak of them as of English or foreign extraction.

We find this castle also in the possession of a branch of the O'Kanes, who settled in the county of Antrim about the end of the 13th century, and who were called Claim Magnus na Buaise, or the Clann Magnus of the River Bush, to distinguish them from another branch of the O'Kanes, called Clann Magnus na Banna, from the situation of their territory on the western banks of that river. But Queen Elizabeth granted this place to Surly Boy (Somhairle Buidhe) M'Donnell, as we are informed by Camden.

"The tract above this (i. e. above the Glinnes) as far as the river Ban, is called Route, being the residence of the Mac Guillies, no inconsiderable family in their own country, though driven into such a narrow corner by the violence and continual depredations of the island Scots. For Surly Boy (q. d. Charles the Yellow), brother of James M'Connell,[1] who had possessed himself of the Glinnes, made himself, by some means or other, master of this tract, till the Lord Deputy, John Perrott, before mentioned, taking Donluse Castle, their strongest fortress, situate on a rock commanding the sea, and separated from the land by a deep ditch, drove out him and his followers. Next year, however, he recovered it by treachery, having slain the governor, Cary, who made a brave defence. But the deputy sending against him Meriman, an experienced officer, who slew here the two sons of James M'Connell and Surly Boy's son, Alexander; so harrassed him, and drove off his cattle, which were his only wealth (he having 50,000 cows of his own), that Surly Boy surrendered Donluse, went to Dublin, and in the cathedral made his public submission, presenting an humble petition for mercy; and being afterwards admitted into the deputy's apartment, as soon as he saw the picture of Queen Elizabeth, he threw away his sword, and more than once cast himself at her feet, and devoted himself to her Majesty. Being thus" received into favour, and among the number of her subjects in Ireland, he abjured all allegiance to every foreign prince, in the courts of chancery and king's bench; and, by Queen Elizabeth's bounty, had four districts given him, called Toughes, from the river Boys to Ban, DONSEVERIG, Loghill, and Bally Monyn (Ballymoney) with the government of Donluse Castle for himself and the heirs male of his body, to hold of the kings of England, on condition that neither he, nor his men, nor their descendants should serve any foreign power without leave; that they should restrain their people from ravaging; furnish, at their own expense, twelve horsemen and forty footmen for forty days in time of war; pay to the king of England a certain number of cattle and hawks annually."--Gough's Camden, vol. iv. p. 431.

That the insulated rock, on which the Castle of Dunseverick is placed, should, from its peculiar strength, have been selected by the early settlers in Ireland as a proper situation for one of their strongholds, is not to be wondered at; but of that original fortress there is no remains. It was, no doubt, like all the ancient castles of a very early date in Ireland, either an earthen dun, or a cahir, or circular stone fort, without cement. The present ruin, though of great strength, the walls being eleven feet in thickness, is evidently of an age not anterior to the English invasion, and was probably erected by the M'Quillans , but our annals are silent as to the period of its re-edification.

I should not have troubled the reader with so many quotations and minute references, had I not felt myself called upon to correct this gross mistake in the geography of ancient Ireland--a mistake which it has been the custom of every writer who has treated of the subject to copy from his predecessors, without examining the grounds on which the statement rested. I am also fully convinced, that unless we quote original and authentic MSS. for the proof of Irish history, our arguments are baseless, and we leave the history of Ireland the same muddy thing which it has always been justly styled.

J. O'DONOVAN

NOTE:-

[1] The M'Donnells of Scotland are called M'Connells in old English records, from an attempt to convey the Gaelic pronunciation in English letters. McDhomnhaill is the original name, and it has nothing to do with Connell, and bears no affinity whatsoever with it, except by corruption, although we have seen them classed together as one and the same name by a gentleman of great research in Irish history. This error must have arisen from a want of acquaintance with the ancient language of Ireland and Scotland