Ancient Irish Bells, or Crotals

From The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 47, May 18, 1833

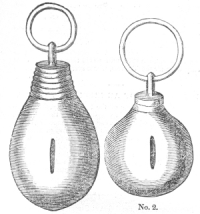

The annexed wood-cuts, represent some ancient Irish bells, which, with a great variety of skeynes, celts, spears, and arrow heads, gouges, metallic pans, and other relics of antiquity, were found a few years ago in a bog near Birr in the King’s county. Many specimens of the curiosities just enumerated, as well as of other rare remains of ancient times, including that unique antique-work in metal called the Barnaan Coolawn, (upwards of nine hundred years old,) of which an account is given in the 14th volume of the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, are now in the collection of T. L. Cooke, Esq. of Birr. The bells are of bell metal, and appear as if gilt. No. 1. is five inches long by two and one half, in the greatest diameter, and No. 2, is three, by two inches and a quarter.

These bells were formerly called Crotals or Bell-cymbals, and are supposed to have been used by the clergy. They consisted, as Dr. Ledwich (Antiq. Tr. p. 251.) writes, and as the specimens before us prove, of two hollow demi-spheres of bell-metal joined together, and enclosing a small piece of the same substance to serve the use of a tongue or clapper, and produce the sound. The learned antiquary just referred to, says, on the authority of Joh. Sarisber, “the crotal seems not to have been a bardic instrument, but the bell-cymbal used by the clergy, and denominated a crotalum by the Latins." He adds, "it was also used by the Roman Pagan priests.”

The name seems to be derived from the Irish, crotal, a husk or pod, which was metaphorically used to express a cymbal. The venerable General Vallancey, in the twelfth number of his Collectanea, intimates that bells might have been employed by the Irish druids, and adduces instances of the ancient augurs having used them in pronouncing their oracles. Walker, in his history of the Irish Bards vol. i. p. 127, tells us that these bells were formerly used by the priests to frighten ghosts.

Cambrensis relates an odd story about the bell of St. Finnan. He writes, “there is in the district of Mactalewi in Leinster a certain bell which unless it is adjured by its possessor every night in a particular form of exorcism shaped for the purpose, and tied with a cord, (no matter how slight), would be found in the morning at the church of St. Finnan, at Clunarech, in Meath from whence it was brought; and, adds he, this has sometimes happened.” The same writer, part 3, dist. 33, observes that these bells were occasionally sworn upon as a species of ordeal dreaded far more than the gospels. Archdall, (Monastic. Hib. at Inniscattery,) mentions that when he wrote, the bell of St. Senan was religiously preserved in the western part of the county Clare, and that the common people used to swear by it. Colgan, in the life of St. Cormac, Acta SS. p. 751, speaking of Cormac’s brother, St. Evin, who founded the monastery of Ros Glas, now called Monastereven,[1] and which he calls Ros-mic-treoin, tell us that his bell was held in high veneration after his death and used to be sworn on. Archdall informs us that St. Evin’s bell was always committed to the care of the M‘Egans, hereditary chief justices of Munster.

We learn from Shee’s publication of O’Phelan’s collections of epitaphs in the cathedral of St. Canice at Kilkenny, that the first bell erected in a church in Ireland, was given by St. Patrick to St. Kieran, who put it up in his church, at Saiger, near Birr. “Primam in Hibernia Campanam opinor cymbalum illud fuisse quod Sanctus Patricius Sancto Kieranno Sagiriensi tradidit, &c.” Vid. Ogygia, par. 3.

The use of bells is supposed to be more ancient in Ireland than in England, in which latter country venerable Bede says they were not used until the end of the seventh century. The first bells are said to have been made about the year 400, at Nola in Campania, whence they took their Latin names, “Nolae” and “Campanae.”

The use of bells is summed up in the following distich:

Laudo Deum verum, plebem voco, congrego clerum,

Defunctos plero, pestem fugo,

festa decoro.

The ancient religious bells of the Irish, thus briefly noticed by our respectable correspondent B., is a subject of considerable interest, and which we shall return to in a future number at some length; we shall, therefore, only observe now that the bells represented by our correspondent, 1 and 2, as well as a 3d which we here add from the museum of the Dean of St. Patricks, and which was found in the same bog, are evidently of very early antiquity, and undoubtedly of that description called crotal or bell cymbal—two of which were always connected together by means of a flexible rod. Beauford, in his Essay on the ancient Irish musical instruments, published in Ledwich’s Irish Antiquities, gives a plate of what he and Ledwich supposed to be the form of the Irish crotals, but which are in reality only sheep-bells of the 17th century, and of which we subjoin a specimen from our own collection.

The crotals given above are the only true specimens of the kind which we have heard of as being found in Ireland; a great number of brazen trumpets, of the same metal, gilt in the same manner, and apparently the ( work of the same workman, were found along with them. These trumpets are in the possession of Lord Oxmantown, The Dean of St. Patricks, and Mr. Cooke, of Parsonstown.

P.

NOTE

[1] Our correspondent, as well as Archdall, is in error in supposing Ros-glas to be the present Monastereven. It is the present town of New-Ross on the Barrow, which is still called in Irish by the name given in Colgan, Ros-mic-treoin. Dr. Lanigan has avoided this error, into which even Ware fell.