Querns and Grain-rubbers in Ancient Ireland

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »

CHAPTER XXI....concluded

2. Querns and Grain-Rubbers.

A grinding-machine much more primitive and ancient than the water-mill was the quern or hand-mill. It was called in Irish bro, gen. brón [brone]: and often cloch-bhrón [cloch-vrone]: cloch; 'a stone'; but both these terms were also applied to a millstone. The upper stone worked on an axis or strong peg fixed in the lower one, and was turned round by one or by two handles. The corn was supplied at the axis opening in the centre of the upper stone, and according as it was ground between the two stones came out at the edge. Sometimes it was worked by one person, sometimes by two, who pushed the handles from one to the other. In ancient times it was—in Ireland—considered the proper work of women, and especially of the cumal or bondmaid, to grind at the quern. Querns were used down to our own day in Ireland and Scotland; and they may still be found at work in some remote localities.

FIG. 185. Complete pot-shaped Quern: 9 inches in diameter: in the National Museum (From Wilde's Catalogue).

The almost universal use of querns is proved by their frequent mention in the Brehon Laws and other ancient Irish literature, as well as by the number of them now found in bogs, in or near ancient residences, and especially crannoges. Some of these are very primitive and rude, showing their great antiquity. Quern-grinding was tedious work: for it took about an hour for two women to grind 10 lb. of meal. It is hardly necessary to say that the quern or handmill was in use among all the ancient peoples of Europe, Asia, and Africa: and that it is still employed where water-mills have not found their way.

In comparatively modern times mill-owners who ground the corn of the people for pay looked on the use of querns with great dislike, as taking away custom. Quern-grinding by the poorer people was regarded as a sort of poaching; and where the mill belonged to the landlord he usually gave orders to his miller to break all the querns he could find; so that the people had to hide them much as they hide a still nowadays. In Scotland laws were made in the thirteenth century to compel the poor people to abandon querns for water-mills, all in the interests of landlords and other rich persons. It was the same in England: in 1556 the local lord in one of the western English counties issued an order that no tenants should keep querns "because they ought to grind at their lord's mill." But these laws were quite ineffective, for the people still kept their querns.

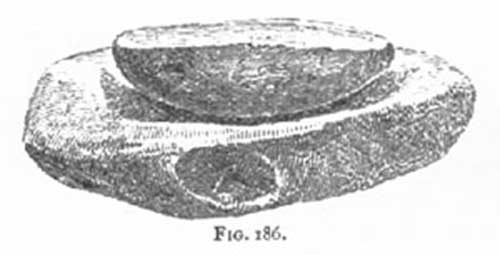

FIG. 186. Grain-rubber: oval shaped: 16 inches long. (From Wilde's Catalogue).

The most ancient grinding-machine of all, and most difficult and laborious to work, was the grain-rubber, about which sufficient information will be derived from the illustration. Several of these may be seen in the National Museum: they are still used among primitive peoples all over the world.

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next chapter »