Armour and the Shield

From A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland 1906

« previous page | contents | start of chapter | next page »

CHAPTER III....continued

Armour.—We know from the best authorities that at the time of the invasion—i.e., in the twelfth century—the Irish used no metallic armour.

Giraldus says:—

“They go to battle without armour, considering it a burden, and deeming it brave and honourable to fight without it.”

The Danes wore armour: and it is not unlikely that the Irish may have begun to imitate them before the twelfth century: but, if so, it was only in rare cases. They never took to it till after the twelfth century, and then only in imitation of the English.

But the tales describe another kind of protective covering as worn by Cuculainn, and by others; namely, a primitive corslet made of bull-hide leather stitched with thongs, “for repelling lances and sword-points, and spears, so that they used to fly off from him as if they struck against a stone.”

Greaves to protect the legs from the knee down were used, and called by the name asán.

Helmet.—That the Irish wore a helmet of some kind in battle is certain: but it is not an easy matter to determine the exact shape and material. It was called cathbharr [caffar], i.e., ‘battle-top,’ or battle-cap, from cath [cah], ‘a battle,’ and barr, ‘the top.’ It was probably made of hard tanned leather, possibly chequered with bars of iron or bronze. The warriors often dyed their helmets in colours: and there was commonly a crest on top.

Shield.—From the earliest period of history and tradition, and doubtless from times beyond the reach of both, the Irish used shields in battle.

The most ancient shields were made of wicker-work, covered with hides: they were oval-shaped, often large enough to cover the whole body, and convex on the outside.

It was to this primitive shield that the Irish first applied the word sciath [skeé-a], which afterwards came to be the most general name for a shield of whatever size or material.

These wicker shields—of various sizes—continued in use in Ulster even so late as the sixteenth century, and in the Highlands of Scotland till 200 years ago.

Shields were ornamented with devices or figures, the design on each being a sort of cognisance of the owner to distinguish him from all others.

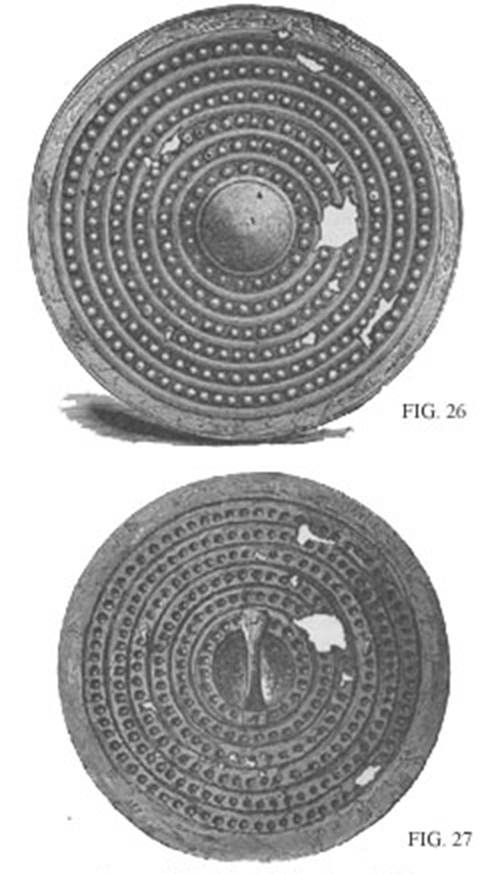

These designs would appear to have generally consisted of concentric circles, often ornamented with circular rows of projecting studs or bosses, and variously spaced and coloured for different shields.

As generally confirming the truth of these accounts, the shields in the Museum have a number of beautifully wrought concentric circles formed either of continuous lines or of rows of studs; as seen in the illustration.

Sometimes figures of animals were painted on shields.

Shields were often coloured according to the fancy of the wearer. We read of some as brown, some blood-red; while many were made pure white. This fashion of painting shields in various colours continued in use to the time of Elizabeth.

Hide-covered shields were often whitened with lime or chalk, which was allowed to dry and harden, as soldiers now pipeclay their belts. Hence we often find in the Tales such expressions as the following:—“There was an atmosphere of fire from [the clashing of] sword and spear-edge, and a cloud of white dust from the cailc or lime of the shields.”

The shields in most general use were circular, small, and light, of wickerwork, yew, or more rarely of bronze, from 18 to 20 inches in diameter, as we see by numerous figures of armed men on the high crosses and in manuscripts, all of whom are represented with shields of this size and shape. I do not remember seeing one with the large oval shield.

Specimens of both yew and bronze shields have been found, and are now preserved in museums.

Shields were cleaned up and brightened before battle.

Those that required it were newly coloured, or whitened with a fresh coating of chalk or lime: and the metallic ones were burnished—all done by gillies or pages.

The shield, when in use, was held in the left hand by a looped handle or crossbar, or by a strong leather strap, in the centre of the inside, as seen in fig. 27, above.

But as an additional precaution it was secured by a long strap, called iris or sciathrach [skiheragh], that went loosely round the neck. When not in use, it was slung over the shoulder by the strap from the neck.

In pagan times it was believed that the shield of a king or of any great commander, when its bearer was dangerously pressed in battle, uttered a loud melancholy moan which was heard all over Ireland, and which the shields of other heroes took up and continued.

The shield-moan was further prolonged; for as soon as it was heard, the “Three Waves of Erin” uttered their loud melancholy roar in response. (For the Three Waves, see chap. xxvi., sect. 9.)