Slieve League - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter VIII: The Donegal Higlands … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

For this country, fine weather is almost essential; but, alas! it is not often granted to those whose time is limited. In short, it cannot be too strongly emphasized that, in order to enjoy Donegal scenery properly, time is essential. A fair idea may be obtained by rushing through the county, and if the visitor has to choose between seeing it under these conditions and not seeing it at all, the author would say by all means visit it even thus. But let all who wish really to enjoy what is unquestionably the freshest, most unconventional, and in many respects most beautiful part of the Emerald Isle, allot considerable time to it. Three weeks or a month spent in doing Donegal thoroughly will be at once a better education in appreciating Ireland and the Irish, and a more complete rest to the mind than six weeks spent in skimming over the greater part of the kingdom. The full enjoyment of a visit to Slieve League, for instance—and by this is meant the careful and repeated study of these stupendous cliffs, with all their rich colouring, and the grand views afforded from different points of vantage, and the leisurely exploration of the five or six miles of headlands, in order to appreciate the wondrous variety of expression they present—can only be obtained in fine weather, and by an expenditure of at least two or three days. The changes of weather, also, are very rapid. A seemingly hopeless day will often rapidly clear, and the visitor, not too much hampered by dates and the daily tale of completed miles, can avail himself of these changes.

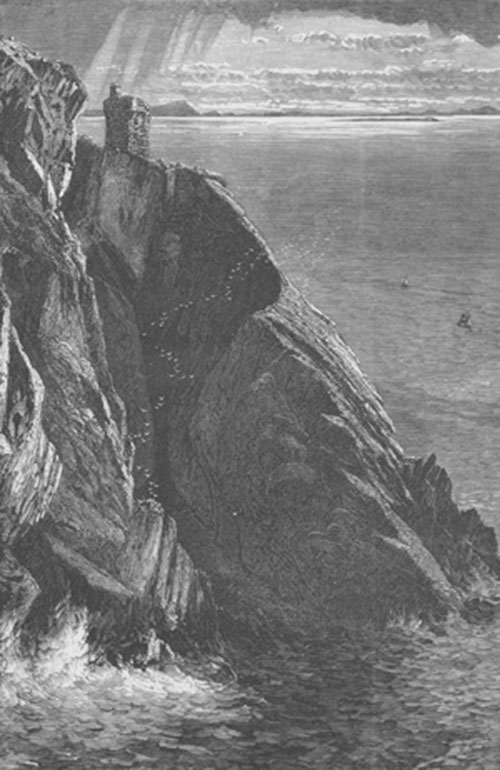

Slieve League is a huge mountain mass, presenting on the land side lofty slopes and valleys, but no forms that specially strike the eye. The sea face has been beaten by the storms of ages into the most superb cliffs in the British Islands. The easiest and best method of exploring it is to walk or drive along the west bank of the Teelin River for a couple of miles, and then turn up the path leading to what is known as Bunglas. The path winds up by easy ascents through a valley leading at length to Carrigan Head. This is a magnificent piece of cliff scenery, a suitable introduction to the greater wonders beyond.

Leaving Carrigan Head on the left, and following the path which winds along the cliffs, Bunglas is soon reached, and one instantly appreciates why the spot obtained the name Awark-Mor, meaning 'the fine view.' The visitor stands upon a point of rock, many hundreds of feet above the sea level. From his right hand there sweeps away a grand semicircle of cliff, rising higher and higher above the sea until opposite where the observer stands it reaches an altitude of nearly 2,000 feet. Beyond this point, the cliffs stretch away for six miles, extending to Malin Beg and Malin More. The sharp bend in the cliffs to the observer's right is sometimes called 'the lair of the whirlwinds,' and the face of the cliffs is exceedingly fine. Their very extent detracts to a large degree from the impressiveness of their height, and it is hard at first to realise that the wave breaking slowly at the foot is, in some places, almost perpendicularly 2,000 feet below the crown of the ridge. Unlike the lofty cliffs of Kerry, this gigantic wall is warm in its colouring. Reddish tints abound, and quartz veins, and bands of shining white quartz, bared and polished by the storms of untold ages, combined with the red-brown bogs, and green mosses, produce colours, which contrast magnificently with the water below and the sky above. Undoubtedly the best way to comprehend the full grandeur of the cliffs is to come round by boat from Teelin Point; but for this trip the finest weather is essential.

The summit of Slieve League is reached by a narrow way known as 'One Man's Path.' About this the most conflicting reports had reached the author. Some described it as a path needing the steadiest nerve, while a gentleman thoroughly familiar with every peak in Donegal, a practised mountain climber, described it as a place one could run down. Great, therefore, was his disappointment when, having reached Bunglas, and fully hoping to test the accuracy of these conflicting accounts, a dense cloud which had persistently rested upon the summit, hiding completely from view the last 200 or 300 feet of the ascent, not only grew denser, but transformed itself into a persistent driving rain. Under these circumstances, he had to leave unsolved the question whether he could easily walk up the ' One Man's Path,' or whether it was an expedition needing a combination of careful guide and steady nerve. It was a melancholy satisfaction to note, some hours later, when he caught his last glimpse of Slieve League from the Kilcar Road, that the heavy cloud still shrouded the top of the mountain, and there was every evidence that the rain was descending even more heavily than when he stood at Bunglas.

The view from Bunglas, once seen, must ever remain a glorious memory. It is also much finer, because more picturesque, than that obtained from the summit, since there the greater part of the mighty cliff wall is hidden. The top is reached by 'a path from Bunglas along the verge of the precipice the whole way up to the top of the mountain. On approaching the summit line, the visitor will find that the mountain narrows to an edge, called the One Man's Path, from the circumstance that they who are bold enough to tread it must pass in single file over the sharp ridge. On the land side, an escarpment, not indeed vertical, but steep enough to seem so from above, descends more than 1,000 feet to the brink of a small tarn; while on the side facing the sea the precipices descend from 1,300 to 1,800 feet, literally straight as a wall, to the ocean. A narrow footway, high in the air, with both these awful abysses yawning on either side, is the One Man's Path, which in the language and imagination of the people of the district is the special characteristic of Slieve League, a distinction that it surely merits. … The view is worthy of this great maritime Alp. Southwards you take in a noble horizon of mountains ranging from Leitrim to the Stags of Broadhaven, and in the dim distance are seen Nephin above Ballina, and, when the atmosphere is peculiarly clear, Croagh Patrick, above Westport. Looking inland you behold a sea of mountain-tops receding in tumultuous waves as far as the rounded head of Slieve Snaght, and the sharp cone of Errigal. … A quarry lately opened shows this part of the mountain to be formed of piles of thin small flags of a beautiful white colour, thus proving, what the geologist would have seen at the first glance, that those quadrilateral pillars standing straight up from the steeply escarped side, and called chimneys by the people, are portions of the formation of the precipice which have not yet wholly yielded to the atmospheric action that has worn the rest into a slope. And here observe how much there is in a name; for Slieve League (or Liaga) means the Mountain of Flags.'[1]

Continuing this, probably the finest coast walk in the United Kingdom, past Malin Beg, and Malin More, Glen Bay is reached, which ultimately becomes Glencolumbcille. That St. Columba was born at Gartan in Donegal, in A.D. 521, seems beyond doubt; that he once lived in this glen has been accepted by many as a fact, although Dr. Reeves, in his splendid edition of Adamnan's Life of the Saint, treats it as a late legend. Some even maintain that the time-worn cross in the churchyard was originally placed there by the founder of Iona. However these things may be, the Glen is a part of the country that no one should miss.

From this point two roads are open to Ardara. The most frequented, that through Carrick, we shall touch upon later. The wilder and much less common is to follow the coast, passing by the Sturrel, commonly known as the Bent Cliff, an extraordinary mass of rock jutting out from the precipices which here form the coast line, and rounding the slopes of Slieveatooey, with Loughros Beg Bay and Loughros More Bay immediately beneath.

NOTES

[1] The Donegal Highlands, pp. 99 100.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »