King John's Castle, Limerick - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter VI: The Shannon … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

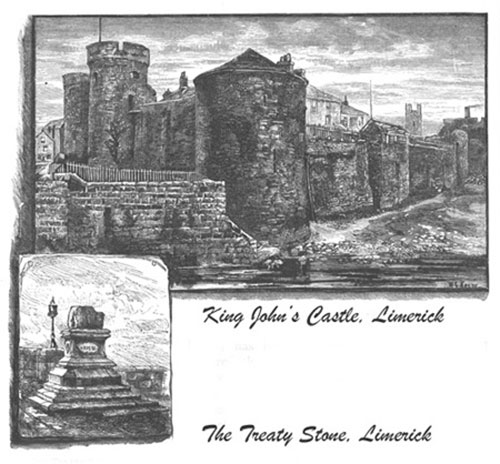

At the western end of Thomond Bridge, raised upon a substantial pedestal which lifts it above the reach of the chipping tourist or the wanton defacer, stands the stone upon which, according to popular belief, the Treaty of Limerick was signed in 1691. The history of this famous negotiation is long and complex. One of the articles stipulated that the Roman Catholics should enjoy the same privileges in the exercise of their religion as they had done in the reign of Charles II., and that they were to be protected from religious persecution. This article does not seem to have been kept, and hence the name so frequently applied to Limerick—the 'City of the Violated Treaty.'

Thomond Bridge gains in picturesque beauty from the fact that at the eastern end stands King John's Castle. This has been greatly disfigured by the construction of unsightly barracks within its precincts; but these have not been able to wholly destroy the fine effect of the old turrets and towers rising above the bold arches of the bridge, as seen from the opposite bank of the Shannon. Frowning down upon the main approach to English Town, the massive gateway and the drum towers tell the tale of force and conquest invariably associated here and elsewhere with the traces of the Norman and Anglo-Norman times. The only other building likely to interest the visitor stands in English Town. This is Limerick Cathedral; it differs from many churches in departing from the crucifix form, and consists of three aisles. It is considered to date from the twelfth century, but it has been so often enlarged, rebuilt, and restored that probably little if any of the original edifice remains. The interior is effective, and there are many tombs in it, some of considerable interest and merit; the two side aisles are divided into chapels. There is a splendid tower at the west end, and from the top a view of this part of the Shannon valley is obtained which no visitor who wishes to appreciate the beauty of the Limerick suburbs should miss. At his feet lies the city, intersected by the rivers, and the eye can easily follow the windings of the cramped streets that occupy the older parts. Away on every side stretches a fine expanse of country. Looking up the Shannon, the stream can be traced a considerable part of the way towards Castle Connell and Lough Derg, while below the city it can be seen hastening on to the noble estuary. On every side the view is beautifully framed in by the near or distant hills which enclose one of the most fertile districts of Ireland.

The tower contains a peal of bells noted for their sweetness of tone, and concerning which the following legend is related:—'The founder of the bells, an Italian, having wandered through many lands, at last, after the lapse of long years, arrived in the Shannon one summer evening. As he sailed up the river, he started at hearing his long lost bells ring out a glorious chime; with intensified attention he listened to their tones, and when his companions tried to arouse him from his ecstasy they found he had died of joy.'

From this point of vantage a fair appreciation of the most brilliant exploit performed by Limerick's military hero, Sarsfield, may be obtained. When, in 1690, William III. was marching upon Limerick, expecting an easy capture, it was only by Sarsfield's energy and courage that the resolution was taken to resist to the last. Things looked gloomy indeed for the Irish cause. William and his army arrived and pitched their tents; at some distance in the rear followed ammunition trains and supplies, together with some heavy ordnance, and a bridge of ten boats. Sarsfield, with the skill of a true soldier, saw that his one supreme hope was to destroy the enemy's train. The incident can hardly be better described than in Lord Macaulay's words: 'A few hours, therefore, after the English tents had been pitched before Limerick, Sarsfield set forth under cover of the night with a strong body of horse and dragoons. He took the road to Killaloe, and crossed the Shannon there; during the day he lurked with his band in a wild mountain tract named from the silver mines which it contains. He learned in the evening that the detachment which guarded the English artillery had halted for the night seven miles from William's camp on a pleasant carpet of green turf, and under the ruined walls of an old castle; that officers and men seemed to think themselves perfectly secure; that the beasts had been turned loose, and that even the sentinels were dozing. When it was dark the Irish horsemen quitted their hiding-place, and were conducted by the people of the country to the spot where the escort lay sleeping round the guns. The surprise was complete; some of the English sprang to their arms, and made an attempt to resist, but in vain; about sixty fell, one only was taken alive. The victorious Irish made a huge pile of waggons and pieces of cannon. Every gun was stuffed with powder, and fixed with its mouth in the ground, and the whole mass was blown up. The solitary prisoner, a lieutenant, was treated with great civility by Sarsfield. "If I had failed in this attempt," said the gallant Irishman, "I should have been off to France."'

Sarsfield returned to Limerick, William was compelled to retreat, and it was not until the following year that Sarsfield honourably capitulated to Ginkell, and retired with a part of his army to France. A fine statue of the general now adorns one of the streets of the city.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »