Valentia Island, Kerry - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter V: Glengariff, Killarney, and Valentia … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

Having enjoyed the lovely scenery of Killarney, no traveller who can spare the time should fail to visit Valentia. By this trip some of the most interesting and characteristic portions of Kerry are to be seen, notably what is known as the Mountain Drive, along the southern shores of Dingle Bay, Glenbeagh, late of eviction notoriety, Valentia Island, and, above all, the coast with its islands, preeminent among these being the Skelligs. It is possible to go from Killarney to Killorglin by train, and thence by omnibus or car to Cahirsiveen. But the best way for any one who wishes to see typical men and things is to go by mail-car. In many parts of Ireland these most convenient conveyances run. They are not luxurious, their cushions are often hard and well-worn, they are not unfrequently heavily laden with parcel-post impedimenta and other mail baggage; and he who travels by them must be prepared to rough it a little, and to be considered possibly a trifle plebeian in his tastes. But for all these things there are ample compensations. They are fast; they are cheap; each car has a driver thoroughly familiar with the country he traverses, and almost invariably civil, obliging, and communicative; the passengers are generally typical peasants, and all along the route little incidents happen, slight in themselves, but of peculiar interest oftentimes to the observant traveller, because they enable him to see the people as they are in themselves, and while engaged in their daily avocations. Just as the ordinary Norwegian steamer is a better conveyance for those who wish to study that interesting people, than the special tourist vessels that run to the North Cape, so the mail-car gives many a trait, life-study, amusing incident, or friendly chat, utterly unknown to those who journey in Ireland only by special car or by tourist-crowded coach or omnibus.

But he who goes from Killarney to Valentia by mail-car has to get up early. It is timed to leave the post-office at 5.30 a.m., and does so, unless detained by the mail-train being late, a state of affairs which the writer knows by experience occasionally happens. This particular route is traversed daily by a 'long car,' that is, one that needs two horses, can carry about a dozen passengers and a heavy load of mail. The first stage is to Killorglin, about thirteen miles, and after the northern end of Lough Leane has been passed, on the left hand the Reeks present a series of exceedingly fine mountain views. From a broad expanse of morass and bog they rise rapidly and boldly, the lower slopes being rounded and massive, but the upper peaks exhibiting a series of wild and craggy pinnacles. Killorglin has nothing attractive about it, except its fine situation above the Laune, which is here crossed by a bridge leading to Milltown and Castlemaine. Beyond Killorglin the road rises by a long ascent, which gradually brings into view Dingle Bay and the range of hills along its northern shore. Six miles on a steep descent, along the valley of the Caragh, leads to Caragh Bridge, which crosses a wild mountain stream rushing down from Lough Caragh. The district does not belie its appearance; it is a noted spot for salmon and trout fishing. Passing through Glenbeagh, the road gradually ascends, and, on turning the shoulder of a hill, a splendid view of Dingle Bay is obtained, and for miles the car runs along the face of the slope high above the sea level. The mountains of Clare on the further shore of the bay are all in full view. Perhaps the chief drawback is the singular absence of shipping, hardly a fishing-boat even being in sight. Leaving the sea, a broad valley is traversed, with mountains on either side, and, crossing Carhan Bridge, Cahirsiveen comes into view. Close to the bridge is a ruined house, of which part of the walls, overgrown with ivy, remain. Here the renowned Daniel O'Connell was born. Cahirsiveen is a poor but apparently thriving little town. It lies embosomed in a bold mountainous country. It is 38 miles from Killarney, and few mail-car rides in Ireland so well repay the fatigue involved in their accomplishment.

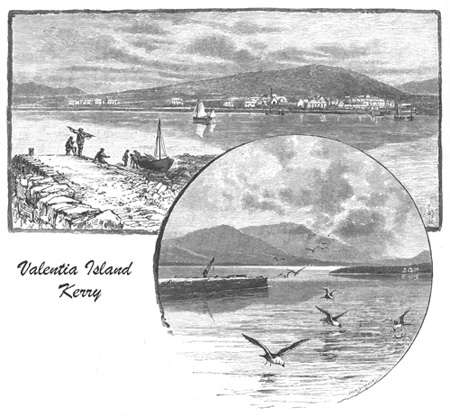

Valentia Island, or rather the ferry, is three miles beyond Cahirsiveen The island is separated from the mainland by a strait half a mile broad. The engraving gives two views. In the circle is depicted the view from Valentia pier; it is identical with that obtained from the windows of the hotel, which is so placed as to face the pier. In the extreme right is seen the house on the mainland from which the ferryboat starts. The other picture represents Knights Town as seen by the wayfarer about to make the passage. The broad strait forming Valentia Harbour, the mountain, the many tones of brown on the hills, the clear sky, the fine colours of the water, combine to make this a scene upon which the eye lingers with delight.

In the extreme left of the larger engraving a little cluster of houses is shown. This is the headquarters of the celebrated Atlantic Telegraph Company. The second building from the left is the house in which the instruments are kept busy day and night constantly receiving and transmitting messages across the Atlantic. The company now possesses three cables, one of which is in direct communication with Embden, in North Germany, by which continental messages are sent direct via Newfoundland and Cape Breton to New York. The public are admitted at stated hours, but the writer, by courtesy of the secretary of the London office, was allowed to inspect the premises during the busiest part of the day. The instruments occupy two rooms. In one the operators are engaged with the Embden cable, some transmitting messages to America; others to various parts of the Continent via Embden. The messages are expressed in all languages, and in various ciphers. As the operator reads the message which is being spelled out by the instrument he transmits it to Newfoundland, and this is so promptly done that the first half of a message is across the ocean before the other has entirely left Germany. In the second room Stock Exchange work, press messages and private telegrams are coming and going. When the writer saw this room four operators were hard at work on the Stock Exchange messages, all in cipher. The superintendent stated that a New York broker is apt to grow impatient if he cannot get a message through to London and a reply in the course of a few minutes! Competition has so increased the companies that the rates are very low; but the low rates have not correspondingly increased the traffic. Although 3,000 messages pass through in twenty-four hours, on the average, this is by no means the maximum that could be dealt with, and meanwhile the shareholders of this company, the pioneers in ocean telegraph work, have to be content with one per cent. dividend. The officials and clerks form a little colony in this extreme south-western nook of Ireland.

The hotel at Knights Town is very comfortable and reasonable, and any visitor tired of such tourist-frequented regions as Killarney or the Causeway, wishing to spend a few days in some breezy, health-giving resort 'far from the madding crowd,' might do very much worse than visit Valentia Island. Bathing, boating, and fishing are all to be had; there are plenty of short excursions; and when the wish to go further afield comes, it is not difficult to sail across to Dingle, and although it is a somewhat formidable trip, it is by no means impossible, as we shall proceed to show, to get out to the Great Skellig, which is by far the most interesting island off the Irish coast.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »