Gap of Dunloe - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter V: Glengariff, Killarney, and Valentia … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

Killarney is a district rather than a town. There is indeed a cluster of streets, lined for the most part by very unattractive houses and shops, and not at all remarkable for neatness. These constitute the town, but no visitor is likely to wish to linger here. But the country about, for fifteen miles or so, especially to the south and west, abounds in peaks that may be ascended, mountain loughs, about which linger grim legends, waterfalls and cascades, passes and glens, trips by car or by boat—in fact, scenery, the chief beauties of which can be exhausted in two days, or which can afford the careful explorer pleasant tasks for weeks.

The most comprehensive excursion is to the Gap of Dunloe and back by way of the lakes. For this a whole day is needed, and the earlier the start the better. A good pedestrian can walk it, but the pleasantest way is to take a car to the foot of the Gap; by this means the five miles of wall are passed quickly, and the wayfarer is fresh for the walk through the Gap, and any excursion that may seem desirable, say the ascent of Purple Mountain, or a stroll up the Black Valley. By this route the Killorglin road is taken, and on the right hand, two or three miles out of the town, the ruins of Aghadoe Church and Round Tower are passed. About two miles or so away from the mouth of the Gap, the first experience of the great Killarney nuisance is encountered. Not far from Aghadoe the road forks, and here, on the alert to catch their victims early, are stationed a collection of the Killarney beggars, misnamed guides. They are mounted on ponies, and their object is to succeed in getting these taken for the ride up the pass. There is no escape from them, and even the plan of engaging one for the purpose of stalling off the others is defeated by the additional swarms that are encountered in the pass. The best plan is to say little or nothing, to buy nothing, and, above all, to drink none of the various mixtures that are offered every few hundred yards along the route. It is really intolerable that these hordes of beggars should be allowed thus to detract from the enjoyment of a very lovely district. But as things are, there seems to be no remedy. One is inclined to hold that if the advocates of Home Rule could make it evident that their panacea would banish the beggars, not only from the Gap, but from all the other lovely parts of the kingdom, they would at once secure the sympathy of all travellers. These would consent to a good deal in order to secure the disappearance of the men and boys who offer ponies for hire, who bring cornets to wake the echoes, and who wish to fire off cannons that look admirably adapted to destroy the individual bold enough to fire them; together with the girls who offer for sale woollen socks and potheen and milk, the whole tribe of Kate Kearney's descendants who sell deplorable photographs of themselves and the huts in which they live, and the miscellaneous crew who look upon every visitor as the possibility of a copper or a sixpence.

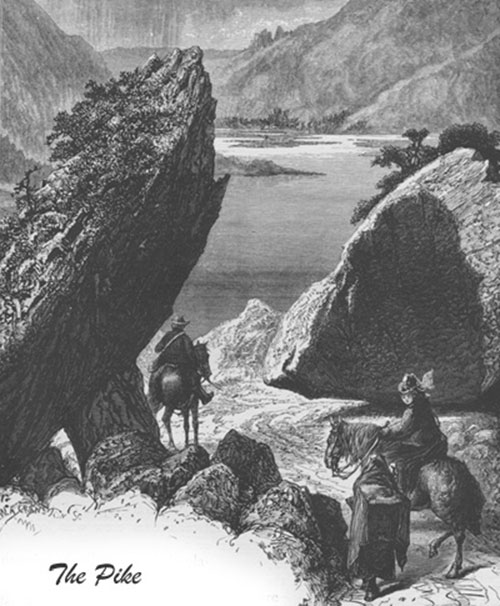

The Gap of Dunloe is a pass between the Toomies and the McGillicuddy Reeks, up which any but the feeblest walkers can go with the utmost ease, from the point where the cars always stop. The River Loe traverses the Gap, expanding at intervals into five lakes. A good road winds up the valley, crossing the stream by bridges in two places. The mountains rise very steeply to a height of over 2,000 feet, and the scenery is very wild. The narrowness of the defile combined with the height of the mountains gives it a sombre and awe-inspiring influence. At one point the ravine narrows, and a huge mass of rock has fallen and split into two irregular portions. The road runs between these enormous stones, which have the semblance of a rude gateway. The spot is known as The Pike. The impression of wildness and desolation is considerably weakened, not only by the troops of beggars, but more legitimately by the number of little farms in the valley, and by the numerous traces of fairly prosperous agriculture. As the ascent is made, very good views to the north are obtained, but by far the finest is enjoyed when the summit of the pass is reached, and the traveller stands with the beautiful Owenreach Valley at his feet, the many-islanded Upper Lake to his left, the Kenmare Road and the Police Barracks directly opposite, and the Black Valley to the right over which tower the rugged pinnacles of the Reeks. Occasionally one meets with absurdly over-drawn descriptions of this Black Valley. When the writer saw it, under a bright April sun, it failed signally to harmonize with its name, since it lay smilingly at his feet, looking most attractive in its beauty.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »