Introduction: Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

« Previous Page | Book Contents | Works Consulted »

FOR some years past many of those acquainted with the 'Pen and Pencil Series' have expressed the wish that Ireland could be added to the list. English Pictures has long been a favourite; the more recent Scottish Pictures received a warm welcome; it seems hardly fair that the Emerald Isle should any longer be omitted.

It would be idle to deny that Ireland, even from this point of view, presents difficulties not experienced in the case of the sister kingdoms. Readers may naturally expect to find in any elaborate book upon Ireland issued at the present moment, some reference to the burning questions of the hour; such, for example, as the relation of tenant to landlord, or the expediency of Home Rule. Absorbing and important as these questions are, the author trusts that it will not detract from either the interest or the value of this work when the reader discovers they have been rigidly excluded. It has not come within' the author's province to discuss them. His object is wider, and, it may be hoped, no less useful.

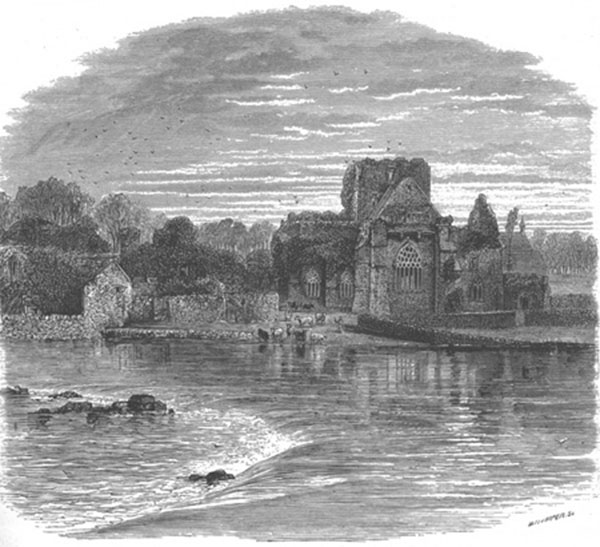

He seeks to give pen and pencil pictures of all parts of Ireland; to produce upon the mind of the reader, so far as it is possible with the means at his command, the impressions that a journey through the country would make upon an observant and unprejudiced mind. This need not and does not indicate indifference to political issues. Far from it. But evidence is not lacking to show that the inhabitants of England, Scotland, and Wales do not know as much as they might and ought about their Irish brethren, and the land in which they dwell. The glorious scenery of Donegal and Kerry, the picturesque ruins of Cashel and the Lower Shannon, the industries of Belfast and Limerick, the splendid past of Ireland—her early Church-life, her missionary enthusiasm, her literature, architecture, and art—present many subjects for consideration and study that ought to command the attention alike of ardent Nationalists, staunch Conservatives, and those who may be unable to sympathise heartily with either section.

The United Kingdom possesses no fairer regions than Killarney and Connemara; no wilder coast scenes than the lofty cliffs and bold headlands that bear, at Valentia, Moher, Achill Island and Slieve League, the whole unbroken force of the mighty Atlantic, and dash into driving foam its wildest waves. There are no more interesting people among the rural populations of Europe than such peasantry as the traveller meets in the Golden Vale of Tipperary, along the mountain routes of Kerry, and amid the lovely scenery of Galway, Donegal, Antrim, and Wexford.

Sad and troubled as much of the past of Ireland has been, she has no reason to fear comparison in regard to the men she has produced. No section of Great Britain can show abler men in their respective spheres of life than Patrick [1] and Columba, Brian Boru and Shane O'Neill, James Ussher and Bishop Berkeley, the Duke of Wellington and Lord Gough, Oliver Goldsmith and Edmund Burke, Henry Grattan and Daniel O'Connell.

There is so much information, both interesting and also not generally known, connected with the early Irish Church, with various periods of Irish history, and with the art and architecture of Ireland, that the author had contemplated giving separate chapters to each of these subjects. But limitations of space, and the fact that these 'Pen and Pencil' volumes are intended for popular reading, have compelled him in this respect to depart from his original plan. But he has not felt it right to omit these important subjects altogether, and hence they have been briefly treated as each seems to arise naturally in the progress of the work. For example, the description of the Royal Irish Academy Museum in Dublin has been made somewhat full, in order that the chief peculiarities of Irish art, as illustrated by its most brilliant achievements, may be indicated. The MSS. of Trinity College Library have been referred to at length, to enable the reader to appreciate the marvellous ability of the ancient scribes who wrote and illuminated them. The personal history of St. Patrick naturally accompanies a description of Slane and of Tara Hill, as some reference to that of St. Columba naturally fits in with a description of Donegal. The origin and uses of the Round Towers—that vexed question—cannot be passed over, and it is dealt with in the description of Clonmacnois, where, within a few yards of each other, two very fine examples have stood for centuries. In this less formal way he has sought—he trusts not less satisfactorily—to deal with all these subjects.

The author has had to treat the religious difficulties of Ireland in much the same way as the political. The tangled and tragic story of the past is one that neither Protestant nor Roman Catholic can find any pleasure in recalling. The conflicting currents and forces that influence the religious life of Ireland to-day have been briefly indicated in the chapter on Belfast. Notwithstanding the experience of the past, and the evidence of so much that is conflicting in the present, the author ventures to hope that better times are in store for the sister kingdom.

The writer has sought to give brief, pointed, and accurate descriptions of all that is most distinctive in Irish scenery; to present a varied and thoroughly representative series of engravings; to glance at some of the most noteworthy men and deeds of the past; and to catch and depict, so far as his pen can, the most typical aspects of the Ireland of to-day.

How far he has been successful must be decided by those who have already given a kindly welcome to Norwegian Pictures, and Pictures from Holland. He can only hope that the Irish readers into whose hands the book may fall will accept his appreciation of, and admiration for, the land they love so well as some atonement for the failings they may observe in his work. As for other readers, he will feel amply rewarded for the time and labour expended upon Irish Pictures if the book enlarges their knowledge of the land known more than fourteen centuries ago as 'the Sacred Isle,' and helps to promote brotherly sympathy towards a people whose history has for some centuries in varied phases been so closely interwoven with that of the English, Welsh, and Scottish races.

The author would gratefully acknowledge the help so courteously given to him by the large number of those whom he met during his various journeys through Ireland, or to whom he applied for special information. He had many opportunities of testing the courtesy and hospitality of the Irish people, and, like others who have borne similar testimony, never found these fail.

NOTES

[1] The Scotch claim Patrick as being born on their soil. This, though probable, is not certain: yet his influence and work were certainly Irish.