St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin - Irish Pictures (1888)

From Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil (1888) by Richard Lovett

Chapter 1: Ireland’s Eye … continued

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »

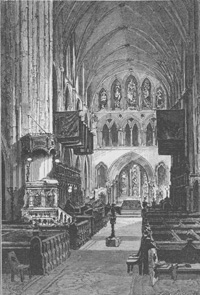

Dublin possesses two cathedrals, both of which, in recent years, have been thoroughly renovated and restored by private munificence. The younger, but in many respects the more interesting, is St. Patrick's.

The early history of this building seems to be somewhat obscure. About 1190, Archbishop John de Comyn, the first English Archbishop of Dublin, built a collegiate establishment here on the site of a much older parish church, and in 1213 his successor changed the church into a cathedral.

In 1362 it was burnt, and in 1370 it was rebuilt, with the addition of a fine tower. In 1542 its constitution was changed to that of a dean and chapter, and in 1546 it passed to the Crown. During this period it was neglected and fell into decay, but in 1554 Queen Mary restored its rights and privileges. It suffered during the Commonwealth troubles, and also at the hands of James II.'s soldiers in 1688. In 1713 the most famous man who has ever been associated with it, Jonathan Swift, was appointed to the deanery. From that time until his death, in 1745, he devoted himself to the preservation of the building and its numerous monuments, and to the increase of its revenues. In 1783, the Order of St. Patrick was instituted, and the banners of the knights now hang in the choir. In 1865 the restoration effected by the wealth of the late Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness was completed. It had fallen into what seemed like hopeless decay, and although some partial attempts had been made to stay the progress of destruction, the building seemed doomed. But by the aid of Sir B. Guinness the building has been so restored that Sir James Ware's description once more applies: 'If we consider the compass, or the beauty, or the magnificence of its structure, in my opinion it is to be preferred before all the cathedrals in Ireland.'

The architecture of the structure is the First Pointed or Early English, and the ground-plan consists of a nave, choir, north and south transepts, all with aisles, and a Lady Chapel. The tower was built in 1370, and the granite spire, a prominent but not at all lovely object, was added to the tower in 1740. The building is 300 feet long, the nave 67 feet wide, the transepts 157 feet long and 80 feet wide, and the tower and steeple 221 feet high. Sir B. Guinness entirely rebuilt the north and south aisles.

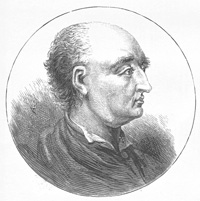

The interior is crowded with monuments, some few of them possessing very special interest. Chief among these is the one dedicated to Swift, who was buried October 22nd, 1745. It stands in the south aisle, and consists of a fine bust, and a slab upon which is inscribed the epitaph written by himself; one of the saddest inscriptions in this or any other cathedral. It is in Latin, but may be freely rendered: 'Here lies the body of Jonathan Swift, D.D., Dean of this cathedral church, where fierce indignation can no longer rend the heart. Go, traveller, and imitate, if thou canst, one who, as far as in him lay, was an earnest champion of liberty.' Close by is the inscription commemorating Mrs. Hester Johnson, or 'Stella,' as 'a person of extraordinary endowments and accomplishments, in body, mind and behaviour; justly admired and respected by all who knew her, on account of her many eminent virtues, as well as for her great natural and acquired perfections.' She was buried by the second pillar from the west door on the south side of the nave, Jan. 30th, 1728, seventeen years before the brilliant but bitter genius of Swift sank to rest.

Swift's life is a tragedy, perhaps the most tragical in the long story of English literature. One cannot look upon the two monuments without wishing that the fate of each might have been different, that Swift could have used his splendid intellect for the good rather than the injury of others, and that Stella's loving heart could have been fixed upon one in whose full and unselfish response she would have experienced a happier lot.

Thackeray's judgment to some seems harsh, but many facts bear it out. 'The saeva indignatio, of which he spoke as lacerating his heart, and which he dares to inscribe on his tombstone—as if the wretch who lay under that stone waiting God's judgment had a right to be angry—breaks out from him in a thousand pages of his writing, and tears and rends him. Against men in office, he having been overthrown; against men in England, he having lost his chance of preferment there, the furious exile never fails to rage and curse. In a note in his biography, Scott says that his friend Dr. Tuke, of Dublin, has a lock of Stella's hair, enclosed in a paper by Swift, on which are written, in the dean's hand, the words: "Only a woman's hair." An instance, says Scott, of the dean's desire to veil his feelings under the mask of cynical indifference. See the various notions of critics! Do those words indicate indifference, or an attempt to hide feeling? Did you ever hear or read four words more pathetic? Only a woman's hair: only love, only fidelity, only purity, innocence, beauty, only the tenderest heart in all the world stricken and wounded, and passed away now out of reach of pangs of hope deferred, love insulted, and pitiless desertion:—only that lock of hair left; and memory and remorse for the guilty, lonely wretch, shuddering over the grave of his victim. And yet to have had so much love, he must have given some. Treasures of wit and wisdom, and tenderness too, must that man have had locked up in the caverns of his gloomy heart, and shown fitfully to one or two whom he took there. But it was not good to visit that place. People did not remain there long, and suffered for having been there.'[7]

In the north transept stands a characteristic specimen of Swift's biting satire, exercised, it must be admitted, more justly in this case than in many. The Duke of Schomberg was killed at the Battle of the Boyne, and buried in St. Patrick's. His relatives do not seem to have cared sufficiently for the duke to contribute towards the cost of a monument in commemoration of his qualities. The inscription, therefore, runs to the effect that the Dean and Chapter had repeatedly and earnestly besought the duke's relatives to erect the monument, that after letters, the requests of friends, repeated and earnest entreaties had availed nothing, the Dean and Chapter had at length erected the stone, in order that the visitor might know where the ashes of Schomberg reposed. The sting is at the end, where it is asserted that the duke's reputation for valour availed more with strangers than his ties of blood did with his own kindred.

This is not flattering to the relatives of the duke, nor, on the other hand, does their conduct indicate that they felt very deeply the loss of the noted soldier; but it is hardly in accordance with fact to characterize the inscription, as Macaulay does, by the phrase, 'a furious libel.'

An hour may be pleasantly spent in deciphering the various monuments and inscriptions; but there are not many of general interest. In the south choir aisle is one in remembrance of the Rev. Charles Wolfe, author of the Burial of Sir John Moore; and in the churchyard one to the memory of Dr. Todd, the archaeologist and author.

NOTES

[7] Thackeray, English Humourists.

« Previous Page | Start of Chapter | Book Contents | Next Page »