Irish Music from the 6th to the 9th Century

Among the numerous Sequences composed by St. Notker is the famous one on the Bridge, the "Antiphona de morte," commencing Media vita in morte sumus—" In the midst of life we are in death"—which was almost immediately adopted throughout Europe as a funeral anthem. Not unfrequently are the words "In the midst of life we are in death," quoted as Scriptural, but the text is only one of the many contributions to the Sacred Liturgy due to Irish writers and composers.

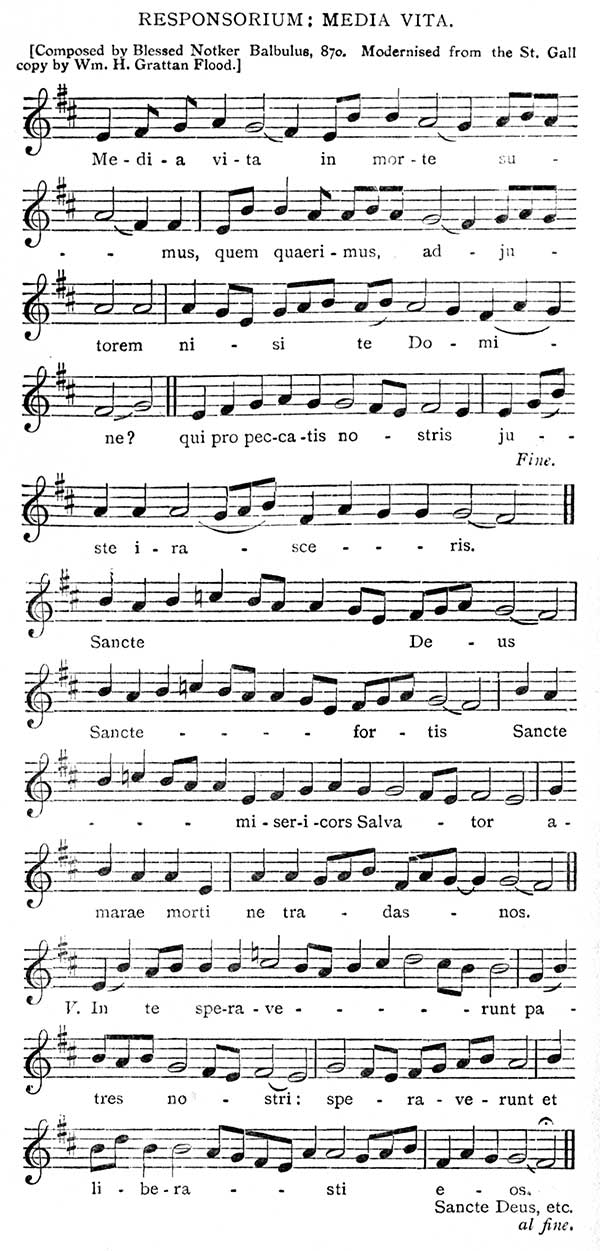

NOTE.—This exquisite Responsorium, also called Antiphona de Morte, from the fact of having been the favourite "anthem" sung at all "offices for the dead" during the Middle Ages, was suggested to Blessed Notker balbulus (the stammerer) by his Irish master, Moengal, or Marcellus, about the year 870. Not only was it superstitiously supposed to be a preservative against death, but the singing of it was believed by many to cause death; and hence, the Council of Cologne, in the twelfth century, forbade the chanting of "Media Vita" without the express permission of the Ordinary of the diocese. The neum-accents merely served as a mnemonic guide for the precentor or choirmaster, showing the number of notes to be sung and the manner of grouping them, but leaving the interpretation as to exact intervals and phrasing to the Cantor, who was required to know all the liturgical chants "in theca cordis." St. Notker also elucidated the "Romanian" signs as taught by Romanus, in 795, as we learn from a letter of his, in a manuscript of the thirteenth century, preserved at St. Thomas's, Leipzig. The earliest known theoretical treatise on church music was by a priest, Aurelian of Réomé, in his Musica Disciplina (850), who described the system as devised for the Western Church by Pope St. Agatho (678-682). St Notker died a centenarian on April 6th, 912.

But why dwell longer on St. Gall's. All Europe must acknowledge its indebtedness to Ireland more or less. The learned Kessel, writing of our Irish monks, says:—

“Every province in Germany proclaims this race as its benefactor. Austria celebrates St. Colman, St. Virgilius, St. Modestus, and others. To whom but to the ancient Scots [Irish] was due the famous 'Schottenkloster' of Vienna? Salsburg, Ratisbon, and all Bavaria honour St. Virgilius as their apostle. … Burgundy, Alsace, Helvetia, Suevia, with one voice proclaim the glory of Columbanus, Gall, Fridolin, Arbogast, Florentius, Trudpert, who first preached the true religion amongst them. Who were the founders of the monasteries of St. Thomas at Strasburg, and of St. Nicholas at Memmingen, but these same Scots? . . . The Saxons and the tribes of Northern Germany are indebted to them to an extent which may be judged by the fact that the first ten Bishops who occupied the See of Verden belonged to that race.”

I have now reached the limit of the present section, namely, the close of the ninth century. The reader has seen that the ancient Irish were acquainted with the ogham music tablature in pre-Christian ages; they had their battle-marches, dance tunes, folk songs, chants. and hymns in the fifth century; they were the earliest to adopt the neums or neumatic notation, for the plain chant of the Western Church; they modified, and introduced Irish melodies into, the Gregorian Chant; they had an intimate acquaintance with the diatonic scale long before it was perfected by Guido of Arezzo; they were the first to employ harmony and counterpoint; they had quite an army of bards and poets; they employed blank verse, elegaic rhymes, consonant, assonant, inverse, burthen, dissyllabic, trisyllabic, and quadrisyllabic rhymes, not to say anything of caoines, laments, elegies, metrical romances, etc.; they invented the musical arrangement which developed into the sonata form; they had a world-famed school of harpers; and, finally, they generously diffused musical knowledge all over Europe.

END OF CHAPTER II.