Wentworth in Ireland

The reign of James I had been passed in one long and constant effort to make the King’s authority over his English kingdom absolute. The great struggle began when James erased from the Journals of the House of Commons the page that reasserted the liberties of Parliament, with the exclamation, “I will govern according to the commonweal but not according to the common will.”

Though the climax of the sovereign’s struggle for autocratic power was not reached till the reign of Charles I, all the elements of future conflict were to be found in James’s defiance of the Remonstrance addressed to him by the Commons on his illegal taxation and his assumption of ecclesiastical prerogatives.

Charles’s doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings was only an expansion of the same principle. A brief period of arbitrary government was to end in England in the execution of the monarch; in Ireland it brought about the rebellion of 1641.

Already in Mountjoy’s time the royal claim had been boldly laid down. “My Master,” he declared at Waterford, “is by right of descent an absolute King, subject to no prince or power upon the earth.”

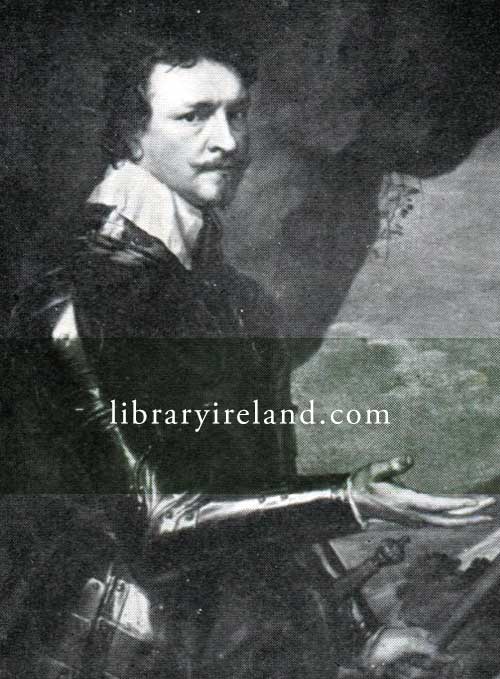

Thomas Wentworth, Lord Strafford.

Wentworth, in the following reign, echoed these sentiments. He silenced all objections to his proposals by “a direct and round answer,” and warned his Irish Council that in consulting what might please the people they “began at the wrong end, when it better became a Privy Councillor to consider what might please the King.”

The same man who in England, as Governor of the North, had drawn up the Petition of Right—the charter of the English people’s liberties,—and who, in words of fire, had called upon his countrymen to “vindicate their ancient liberties,” in later life gave his Irish Parliament to understand that even discussion was beyond their rights. There is no more singular change of front in history than that which transformed Wentworth from the patriot leader into the willing agent of despotism. But the change had been accomplished before he crossed to Ireland. He came over as the avowed instrument of the King. His system of government was communicated in various letters to his friend Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury.

“Let us, therefore, in the name of God, go cheerfully and boldly; if others do not their parts, I am confident the honour shall be ours and the shame theirs; and thus you have my Thorough and Thorough.”

This phrase became a watchword with Wentworth.

“But let it go as it shall please God with me, believe me, my Lord, I shall be still Thorough and Thoroughout, one and the same.”[1]

“That star of exceeding brightness but sinister influence,” as Hallam calls Sir Thomas Wentworth, was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in the year 1632. He became in the year before his execution the Earl of Strafford.

In this man the absolute monarch found an absolute servant, an instrument exactly fitted to his will. Yet though their aims were the same the notion of Wentworth as to how arbitrary power was to be attained was not precisely that of Charles I.

The lifelong struggle of the King was to get rid of Parliaments and to free himself from the goad and check of all constitutional forms. But Wentworth clung to the figment of constituted authority. He would preserve the body when the soul was extinct.

The ideal of the Deputy was a Parliament existing indeed, but existing solely to register and enforce the will of his master, thus giving a semblance of popular support to measures which there was no choice but to accept. His main purpose, openly proclaimed, was to rule Ireland well in order to supply men and money to the King. He would make the country prosperous in order to wring from it abundant taxes for his sovereign; but he aimed at its entire submission and the transference of what remained of Irish soil to English owners. And so well did he succeed that he was able to boast at the end of his term of office that he had left the country prospering, its debts paid, its revenues increased, the army paid and disciplined, the poor relieved, the rich awed, and justice done to all alike.[2]

Wentworth did not arrive in Ireland until the summer of 1633, more than a year after his appointment. It shows the condition of the high seas at this time that pirates on the watch swooped down on the ship bringing over his household goods and belongings, and carried them all off. The Deputy had his revenge. He put down piracy with a strong hand, and in 1637 he was able to report that “there was not so much as a rumour of Turk, St. Sebastian’s man, or Dunkirker” along the coast and that merchants might at last pursue their commerce in peace.

Wentworth’s predecessor, Cary, Lord Falkland, had been dismissed from office on account of his disgraceful treatment of the O’Byrnes of Wicklow. The unsuspecting Deputy was engaged in what he believed to be the worthy and acceptable task of ousting the O’Byrnes and O’Tooles from their picturesque estates in the loveliest part of Co. Wicklow, and planting them with English settlers. The wild and inaccessible country possessed by these septs, which extended through Glendalough, Castle Kevin, and Glenmalure to Castledermot on the land side and as far south as Wexford down the coast, had hitherto made it difficult to penetrate, and the Deputy was not likely to have forgotten the fate that overtook Lord Deputy Grey and his picked body of officers and men when they had pursued Lord Baltinglas and Fiach MacHugh O’Byrne into the steep and wooded recesses of Glenmalure in 1580, and few had returned alive.

In the lifetime of Fiach the farmers of the Pale led an unquiet life, ever expecting a sudden descent upon themselves or their flocks from the most redoubtable man in Leinster after the death of Rory Oge. On him “all the rebels of Leinster might depend”; but they must “use what religion he listed.” If a prisoner was to be set free from Dublin Castle, Fiach was always ingenious enough to secure his escape, and his fort in Glenmalure was a safe refuge; here it was that Hugh O’Donnell had lain in hiding before he escaped to his own country across the borders of Ulster.

It was with the two sons of this independent chieftain, Phelim and Redmond, that Falkland came into contact. They had joined Tyrone’s rebellion and in May 1599 Phelim had routed a strong force under Sir Henry Harington. He was pursued by Mountjoy, who surrounded his dwelling and found him at supper with his family; and he barely escaped by jumping out of the window and concealing himself in the forest, leaving Mountjoy and his men to consume his supper. But in May 1601 he was pardoned, and in 1613 he represented Co. Wicklow in Parliament.

Fifteen years later, in 1628, Lord Falkland set on foot his scheme of planting the O’Byrne lands and he twice tried to involve Phelim in a charge of conspiracy. But the Commissioners of Irish affairs stepped in, and when Falkland shut up Phelim in Dublin Castle a demand came over from England that a full enquiry should be made by a committee of the Irish Privy Council.

Phelim was declared innocent and set at liberty, and the verdict was followed by the astonishing sequel of the dismissal of the Lord Deputy, who had certainly never contemplated the possibility of the King taking the part of the ‘rebels’ against his Deputy. Was he not merely “reducing Phelim’s country to the conformity of other civil parts”? “Was the Court of England to become the resort and sanctuary of the traitors of Ireland?” he wrote angrily.[3] But his querulous letters were of no avail; the King ignored them, and Falkland had to go. Phelim was said to be “of such extraordinary obedience that discreet men would be respondents for him.”

When in 1626 a loyal Address was presented to Charles soon after his accession by the Irish peers and gentry protesting their devotion to his person and repudiating the pretensions of any foreign prince, prelate, or potentate, Phelim, “the prime man in the County of Wicklow for command and dependency of men,” signed the Address. Along with him were Donnell “Spaniogh” Kavanagh and Morgan Kavanagh, who, as representing the old Leinster kings, possessed the seal of the kingdom of Leinster, and Florence FitzPatrick, grandson to the Lord of Upper Ossory, “of whose lands a great part had lately been planted”; all men with great power over the Irish in those counties.[4]

The difficulties with which Wentworth had to contend in his attempt to bring some sort of order into the diseased commonwealth over which he was sent to preside are set forth in a vivid way in a pamphlet written in or about 1623 by an Anglo-Irishman who, though he wrote in England, seems to have studied economic affairs on the spot.[5] He may have been a member of a commission appointed in 1622 to inquire into the condition of Ireland with special reference to the recent plantations. The state of things he reveals is that of an almost universal corruption in all departments of government. The State was preyed upon by a host of insatiable “sharks” of obscure birth, who sacrificed alike the revenue of the King and the public good, by “ingressing” most of the wealth of the realm to themselves, many of them having raised their estates from nothing to an incredible value “in a trice of time.”

The fees exacted for compositions of lands often amounted to half the purchase money, and frauds of all sorts were committed both upon the owners and upon the Crown in the passing of estates by the Commission upon Defective Titles. The writer insists that it had not been the sovereign’s intention to pass these lands to new owners, but to settle the old owners on their estates by a more secure title at an enhanced rent. But in the general unsettlement of land tenures the way was left open for all kinds of fraudulent dealing, and this was fully taken advantage of by the corrupt officials by whose means the business was transacted.

In every department of the public service corruption prevailed, and the central administration was too weak to check it. Like other observers, he imputes the comparative failure of the new plantations to the difficulty of getting the purchasers to go over and undertake the development of their own properties.

“Gentlemen in England give away their lands to footmen and others who now live in the houses of the principal natives and overtop them with more sway and authority than their lord and master would do were he there in person.”

Nearly all the plantations in “Low Leinster,” i.e., Leitrim and Longford, are still “under natives,” but they have been removed from their own rich lands in the plains to the barren mountains, and not a fourth part of their old holdings is left to them. Those that prove to be gentry among them, “of whom there be a great number though they have not sixpence to live upon, disdain to follow any trade; … they live in other men’s houses and spend their days in idleness.” These gentlemen outlaws were to form the inflammable soil in which the seeds of rebellion were to spread with terrible rapidity in 1641, and the dissatisfied transplanted cottiers were to form their bands of followers.

Wentworth’s opinion of the Council with which he was to work was tersely expressed in his first letter from Dublin. “I find them in this place,” he writes, “a company of men the most intent upon their own ends that ever I met with.”[6] “They had no edge at all for the public” and were leagued to keep the Deputy in the dark about everything.

Sir William Parsons, the chief mover in the Wexford plantation, he found “from first to last the driest of all the company,” and with Lord Cork he was on the worst terms. There was a certain incorruptibility as to personal gain in Wentworth which was incomprehensible to these men, all intent on their own advancement. “Old Richard,” as he calls Lord Cork, had his opportunity later when, as Lord Strafford, he stood arraigned for treason to the master whose cause it had been his one wish to serve, and he did not fail to take it. “Old Richard,” he writes from the Tower, “hath sworn against me gallantly, and, thus battered and blown upon on all sides, I go on the way contentedly, and gently tread those steps which, I trust, lead me to quietness at last.”[7]

Richard Boyle, first Earl of Cork, had substantial reason for his hatred, for Strafford fleeced him unmercifully for the public good. He said in 1640 that he was the worse for him by £40,000 in his personal estate and £1200 a year in his income.[8] No doubt the Deputy felt that the money would be much more advantageously employed in the King’s service. A hardly less irritating cause of complaint was Wentworth’s insistence on the removal to one side of the pompous monument erected by Cork to his wife’s virtues in front of the altar in St. Patrick’s Cathedral,—a snub that the Earl was not likely to forget.[9]

Wentworth found much to remedy in the outward appearance of things; the Castle he found falling to pieces, and the Deputy’s horses were without a stable since the ecclesiastical commissioners had reclaimed St Andrew’s Church, which had been used for that purpose. The vaults under Christ Church Cathedral, which the Deputy and Council attended every Sunday, were let for “tippling houses for beer, wine, and tobacco,” of which the fumes could be perceived in the church above. An old diary by Sir Edward Denny, a planter in the south-west of Ireland, gives in one pregnant sentence, the general impression produced by Wentworth’s advent. On July 23, 1633, is found this entry; “The Lord Viscount Wentworth came to Ireland to governe the kingdom. Manie men feare.”