Shane O’Neill and the Scots in Ulster

The new claimant to the title of O’Neill, Shane “The Proud” (an diomas) proved to be one of the most formidable antagonists of the English authority in Ireland with whom Elizabeth’s agents had to deal.

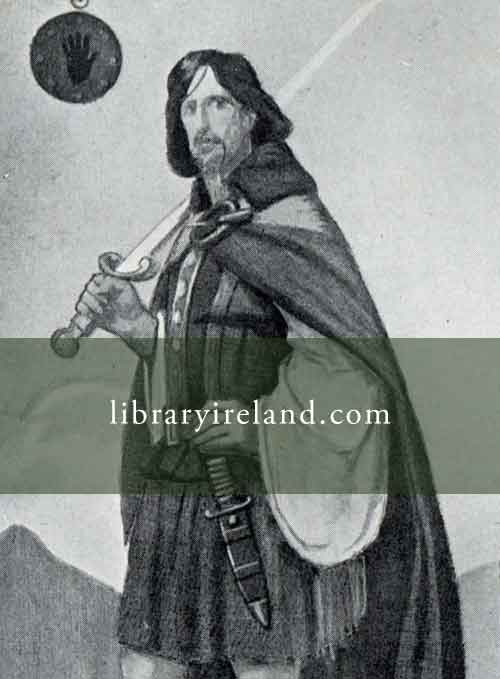

Shane O’Neill

From a portrait at Castle Shane, Ardglass

The sense of wrong with which Shane naturally regarded his position no doubt increased in him that arrogance of temper which not only comes out in his own speeches, but is commented on by every English Deputy with whom Shane had to do, “I believe Lucifer was never puffed up with pride and ambition more than that O’Neill is,” wrote Sidney to Leicester in one of his most exasperated moods.

Shane had some cause for his pride, for in the height of his power he could put into the field a thousand horse and four thousand foot, and he moved about accompanied by a bodyguard of six hundred armed men. A prince constantly in communication not only with Scotland, but with Charles IX and the Cardinal of Lorraine, who armed all his peasants, and who, as the Viceroy admitted, “is able, if he will, to burn and spoil to Dublin gates and go away unfought,” was a menace such as the Crown had seldom encountered, and it was safest to deal with him cautiously.

The Baron of Dungannon had early been put out of his way by assassination, as it was believed, at the direct instigation of his rival Shane. On Elizabeth’s accession to the throne she decided to recognize Shane’s claims to the earldom of Tyrone, and in return she called upon Shane to submit to Sussex, then her Deputy in Ireland.

The chief, however, flatly refused to meet Sussex without hostages for his safety. He had just been elected O’Neill by the suffrages of his sept, and he was engaged in large designs, which gradually took shape in his mind as a Catholic confederation of which he should be the head, to oppose alike the attempts to establish the new faith and the supremacy of the English kings over the Church and country.

He was inviting the Scots to his aid, although his private opinion of them was that “than the Scots he can see no greater rebels nor traitors”; he was defeating successive incursions from the Pale into Ulster, and was carrying on endless wars with his turbulent neighbour, Calvagh O’Donnell. He refused to surrender his ‘urraghs’ or rights over his subject chieftains.

The authorities “found nothing but pride and stubborness in Shane” when they went to ‘parle’ with him; they reported that he was “all bent to do what he could to destroy the poor country”;[1] and “after some arrogant words spoken” they had to depart without him.

Shane’s disinclination to come within the power of the English Deputies was not without cause. At a later date he set out at length for the benefit of the Queen a long list of accusations of atrocious attempts that had been made upon his own life and that of other chiefs by poison and assassination, even when they had come in on pledges of safety.[2] This list reads like an Italian State Paper under the Medicis, and though, later, Elizabeth expressed her horrified displeasure at the attempt of one Smith, in 1563, brother to a Dublin apothecary, to poison Shane in his wine and committed the would-be murderer to prison,[3] there is no doubt that Sussex, and later even Sidney, were persistent in their attempts to put Shane quietly out of the way.

It is little wonder that when Sidney proposed that Shane should meet him at Drogheda the latter arranged a date on which he knew Sidney could not attend. He wrote that although “he knew Sidney’s sweetness and readiness for all good things,” his “timorous and mistrustful people” would not allow him to run the risk of leaving his own territories.

Shane’s quick wit and Irish humour, which never failed him in any emergency, made a way out of the difficulty. He invited Sidney instead to visit him. He had a new-born son about to be christened; he would like Sidney to stand as sponsor. A tie so close and spiritual would be a bond of common faithfulness on the strength of which he was ready to do all that the queen desired of him. Sidney agreed, and was magnificently entertained, Shane’s liberality in household expenditure being famous.

Until the christening was over, no question of business was discussed. Then, in a lengthy conference, Shane laid his claims to the headship of his sept before the future Deputy, then Lord Justice. He had an unanswerable position, and he placed it with such skill and clearness before Sidney that he seems to have acquiesced in the justice of his cause.

Shane, in spite of the degradation of his later life, was a man of great natural ability. He wrote excellent letters both in Irish and Latin, seasoned with a sharp caustic flavour, which showed him well able to maintain his cause even against the Machiavellian statecraft of his day.

It is clear that Sidney was impressed by the man with whom he was dealing, and he concluded the conference by an assurance that the Queen would without doubt act justly by Shane, advising him to live at peace until her pleasure should be known. Shane seems to have taken this advice, and until Sussex replaced Sidney in the negotiations the bond of amity remained unbroken.

Shane’s chief ambition was the retention of the title of O’Neill, a dignity that stretched back to Niall of the Nine Hostages in the fifth century. In comparison with it, the title of the Tudors to the throne might well seem to its holder a mushroom growth, and the title of Earl of Tyrone, which Elizabeth was willing to grant, had a new and unaccustomed sound.

His contempt for the English dignity was shown by his gift of the robes and gold collar bestowed on his father by Henry VIII to the Duke of Argyll, when he sought for his help against Calvagh O’Donnell.

When the time came the Queen had to receive Shane in state in his saffron shirt. But neither Shane nor Ferdoragh (Matthew) could adopt the title of O’Neill without the suffrages of the whole clan, and it was not till 1559, after his father’s death, that Shane was elected O’Neill with all the ancient ceremonies, in open defiance of English law.

Between Shane and Sussex friction was constant, each one endeavouring to gain an advantage over the other. But in 1561 an invitation came from the Queen to Shane to visit her in London, and Shane agreed to go, having first stipulated for a large sum of money to pay all the expenses of the journey for himself and his retinue—a request only reluctantly admitted, for there was little certainty that the money would be applied to the purpose for which it was provided. It might quite conceivably, in Shane’s hands, be used against the Government that provided it.[4]

Shane arrived in the capital on January 4, 1562. He and his galloglas strode through the astonished crowds in London, clad in native attire, a loose, wide-sleeved saffron tunic with shaggy mantle flung across the shoulders. Their heads were bare, their hair was curled down on their shoulders and clipped short just above the eyes in front. In spite of Sussex’s suggestion that he should have a cool reception, as best fitted for a rebellious chief, Elizabeth, who, notwithstanding her imperious temper and the subtlety of her statecraft, was a woman, received him with such warmth that a joke went round among the courtiers that this was “O’Neill the Great, cousin to St Patrick, friend to the Queen of England, and enemy of all the world beside.”[5]

The form of Shane’s submission in a manuscript now in the British Museum runs as follows:

“O my most gracious sovereign lady and queen, like as I, Shane O’Neill, your Majesty’s subject of your realm of Ireland, have of long time desired to come into the presence of your Majesty to acknowledge my humble and bounden submission, so am I now here upon my knees (by your gracious permission) and do most humbly acknowledge your Majesty to be my sovereign lady and Queen of England, France, and Ireland. And do confess that, for lack of civil education, I have offended your Majesty and your laws for the which I have required and obtained your Majesty’s pardon. … And I faithfully promise, here before Almighty God and your Majesty, as a subject of your land of Ireland as any of my predecessors have or ought to do. And because my speech [in] Irish is not well understood, I have caused this my submission to be written in English and Irish, and thereto have set my hand and seal. … Mise O’Neill. [I am O’Neill].”[6]

There were present on this occasion attending the Queen, the Duke of Norfolk, the Earls of Arundel, Huntingdon, Bedford, Warwick, and others of the English nobility, and with them the ambassadors of the King of Sweden and the Duke of Savoy. The Queen capitulated completely to the seductions of Shane. She confirmed her former promise as to his retention of the coveted title of O’Neill “until he should be decorated by another honourable name”; and handed over to him the service and homage of his ‘urraghs’ or tributary lords, who had been relieved of their obedience to his father Conn by Henry VIII.[7]

The rents paid by these tributary chiefs, the Magennesses, O’Hanlons, Maguires, and others had often to be exacted by force, and were the cause of bloody battles between the ‘urraghs’ and their provincial head. They sometimes claimed even from the O’Donnells. “Send me my rent,” said an O’Neill, “or if you don’t …!;” “I owe you no rent,” was an O’Donnell’s retort, “and if I did …!”

Shane was retained long in London, for though Elizabeth’s word had been given for his safe return, nothing had been said about the length of his stay. Neither side trusted the other. Shane was forced to sign conditions against which he protested in vain; and on his way home attempts were made to waylay and assassinate him. His own view of the real trend of events is contained in a letter written to arouse Desmond’s brother John FitzGerald, against the English.

“Certify yourself that Englishmen have no other eye but only to subdue both English and Irish of Ireland, and I and you especially. And certify yourself also that those their Deputies, one after another, hath broken peace and did not abide by the same. And assure yourself, also, that they had been with you ere this time but for me only.”[8]

In spite of the treaty of peace signed at Benburb in November of the next year, 1563, it seems only too probable that Shane’s suspicions were justified. Two years after his visit to London we find the Queen writing to Sidney:

“As touching your suspicion of Shane O’Neill, be not dismayed nor let any man be daunted. But tell them that if he arise, it will be for their advantage; for there will be estates for those who want.”

This sinister suggestion is perhaps the first open avowal of the policy of plantation which was forming itself in the official mind, and the results of which were to transform the whole conditions of the country.

Shane, on his side, played a double game. He intrigued with the Queen of Scots and with the Cardinal of Lorraine, promising to become the subject of France if he could get assistance in expelling the English. On the other hand, when he refused to set free the Lord of the Isles, James MacDonnell, he declared that “the service that he went about was nothing but his Prince’s” and that “it lay not in himself to do anything but according to the Queen’s direction”; and MacDonnell died soon after from the miseries to which he was subjected.

Shane soon “breaks his bryckle peace”; he invaded the Pale, burned Armagh, then occupied by English troops, and tried to incite Desmond to rise. His attempt to make a reconciliation with the Scots was intercepted and stopped by Sidney, who marched with a large army into Tyrone and Tyrconnel, and captured Donegal, Ballyshannon, Belleek, and Sligo.

Shane had been proclaimed a traitor in August 1566; and the union of the O’Donnells with the English brought about a defeat which nearly annihilated his forces near Letterkenny. It was in these circumstances that he accepted the treacherous invitation to meet the Scots at Cushendall which resulted in his miserable death.

The invitation was ostensibly to lead to a permanent alliance between him and Alexander Oge, fourth brother of Sorley Boy MacDonnell, but its acceptance was, in the words of the Annals of the Four Masters, “an omen of the destruction of life and cause of death.” His treatment of their chiefs had earned their undying enmity, and once they had him in their power they showed him no mercy.[9]

During the long wars of Shane with the English Government it is said that three thousand five hundred of the Queen’s forces were slain and that the cost to her Majesty was £147,000. More than once the English troops seem to have been daunted in their attacks on him. “He is the only strong man in Ireland” was Sidney’s comment on returning from his visit to the north in 1565.

At the height of his power, he would boast that he never made peace with the Queen but by her own seeking.

“I confess that she is my sovereign; but my ancestors were kings of Ulster, and Ulster is mine, and shall be mine. O’Donnell shall never come into his country, nor Bagenal into Newry, nor Kildare into Dundrum or Lecale. They are now mine. With the sword I won them; with this sword I will keep them”

—an excuse equally valid for possessions unjustly or justly won.[10]

The pride that was at the bottom of Shane’s character came out with equal vigour in the estimates he formed of his fellow-chiefs. When he heard that MacCarthy had been created Earl of Clancar, “A precious earl!” quoth he, “I keep a lackey as noble as he.”

In spite of the exhortations constantly given him by his English friends “to change his clothes and go like a gentleman,” Shane seems to have retained the manners of his ancestors, after a brief exercise of “civility, justice, and Christian charity” which followed on his visit to London. But his province was not uncultivated, in spite of the curse laid by Conn his father on any who among his posterity should “learn to speak English, sow wheat, or build castles,” and the English troops cut down his corn fields as they wasted Ulster in their pursuit of him.

Between Shane’s own wars and the efforts of the English to subdue him western Ulster lay waste, Shane’s own share in the destruction of his province being not a small one. “The Calvagh O’Donnell is witness that five hundred competent persons, besides above four thousand poor have perished through Shane O’Neill’s spoils,” reads one report. There was much of the Oriental despot about Shane. Of his cruelties to Calvagh we shall have to speak later.

When he was besieging Dunseverick he kept Sorley Boy, who was in his power, for three days without food in order to induce the Scottish garrison to yield.

Yet more brutal was his treatment of the women who fell into his hands. When he could not wreak his vengeance on Calvagh he captured his wife, Catherine MacLean, who had formerly been wife of Archibald Campbell, fourth Earl of Argyll. What this “very sober, wise, and no less subtle woman,” a refined and cultured lady, “not unlearned in the Latin tongue, speaking good French and it is said some Italian,” must have suffered in Shane’s castle it is not difficult to imagine. Her captor “kept her chained all day to a little boy” and only released her for his amusement in his drunken bouts. She was at first his mistress, but in 1565 he seems to have married her. She was the mother of Hugh Gavelock (gaimhleach), “of the fetters,” who was killed by order of Tyrone as a rival in 1590, and of Art, who with his stepbrother Henry and Hugh Roe O’Donnell made the memorable escape from Dublin Castle across the Wicklow Mountains in 1591.

Shane’s private life was dissolute and brutal even for his day. Sidney reports, “Shane hath already in Dundrum two hundred tun of wine, as I am credibly informed, and much more he looketh for,” and we find comments on “the superfluity of wine which Shane daily useth and his pernicious counsellors.”

Nevertheless he was a foe of whom the English had cause to speak with respect. Sir George Carew, who was not given to speaking well of his Irish opponents, calls him “a prudent, wise captain, and a good giver of an onset or charge upon his enemies … from the age of fourteen always in the wars. Some however said he was the last that would give the charge upon his foes and the first that would flee.”

In Carew’s opinion “he could well procure his men to do well, for he had many good men according to the wars of his country.”

Carew also says of him that he was “a courteous, loving, and good companion to those he loved, being strangers to his country.”

He had already planned and partly carried out a plantation of his own people in the Ards, pushing out the Earl of Kildare, who had proposed to do likewise, and he had strongly fortified Ardglass, a trading town whose commerce he was enlarging and the old Norman towers of which still remain to show that the now sleepy fishing village had once been a centre of importance.

So quiet and attractive were some districts of Ulster in Shane’s time that not only Scots, but farmers from the Pale, came to settle down in his country. The free life under Shane was less burdensome than the constant turmoils of the Pale and the heavy charges and rates incurred there. Sidney’s early opinion was:

“His country was never so rich and so inhabited; he armeth and weaponeth all the peasants of his country, the first that ever did so of an Irishman; he hath agents continually in the coor [? Court] of Scotland and with divers potentates of the Irish Scots.”

A very remarkable episode in Shane’s career is that of his relations with Richard Creagh, appointed Papal Archbishop of Armagh under Shane’s rule. Shane expected the support of Creagh in stirring up disaffection in his province. Instead, the Archbishop steadily preached loyalty to the Crown even from the pulpit of Armagh Cathedral. On one occasion Shane attended at the head of six hundred of his fighting men to hear a sermon that he had beforehand instructed his archbishop to preach to encourage his retainers to attack their English enemies. Instead, the sermon was addressed to encouraging loyalty in the troops. Shane, furiously angry, swore “with most loud angry talk” (the report is by the Archbishop himself) “to destroy the Cathedral, which thing he performed a few days later, causing all the roofs to be burned and some of the walls broken.” “He swore that there was no one he did hate more than the Queen of England and his own archbishop” and never again would he hear him preach. But the sermon bore fruit in bringing over O’Donnell to the Queen’s side, he “leaving Shane and giving high thanks to the preacher.”

Though Shane tried to buy the Archbishop with gifts and, when these failed, endeavoured to undo him as a heretic, no fear would make Creagh shrink from doing “his duty owed to God and sworn to his prince,” and he excommunicated Shane in the open field. The loyalty of Creagh is the more remarkable when we know the life of peril that he led; it did not save him from the fate which lay before many of the devoted men who braved the terrors of the time to return to Ireland and preach to the Catholic people.

We learn the outline of Creagh’s life from his own replies to interrogatories made at various times during his imprisonments. They are stamped with the mark of a simple sincerity. He was a native of Limerick and had been educated at Louvain, where he took the degree of Bachelor of Divinity, and then he seems to have returned to his native town as a teacher of children, until, at the command of a Papal nuncio who had been sent to examine into the state of the episcopal sees in Ireland, he felt obliged to go to Rome with a recommendation that he should be consecrated to the Archbishopric of Cashel or of Armagh.

The humility of his mind and the fear of what he would have to face made Creagh most unwilling to undertake either post. He earnestly besought that he might be permitted to enter a religious order, and it was only at the express command of the Pope that he consented to receive consecration and to proceed to Armagh to take up his duties as archbishop. He was uncertain whether Shane would regard him as friend or foe, for Shane had wished to appoint another man.

Creagh tried to induce Shane to erect schools “wherein the young might be brought up in good manners and the beginnings of learning; thinking earnestly that they should long ago forsake their barbarous wildness, cruelty, and ferocity, if their youth were brought up conveniently in knowledge of their duty toward God and their princes.” Creagh gives a terrible account of the moral condition of Shane’s country, in which no punishment was done for the most heinous crimes and ill-living.[11]

The Primacy itself carried with it so small an income that the Government’s bishop, Loftus, some years later, prayed to be transferred to the Bishopric of Meath, because he could not live on the £20 a year which was all that it brought in Creagh’s career was a troubled one. He was distrusted and disliked by Shane, because of his loyalty to the Crown, yet in the eyes of the Government he was only “a feigned bishop,” as having been appointed by the Pope, and therefore, to the official mind, a man whom it was good service to apprehend.

The Crown did not recognize bishops sent by the Popes and owning their authority; while the Crown appointments were not held valid in Rome. From the early days of the Reformation two distinct hierarchies existed side by side in Ireland, though in the dangerous years of Elizabeth’s reign many of the bishops sent over by the Pope never reached their dioceses, which they could only visit at the peril of their lives or liberty.

Bishop Creagh was imprisoned at different times in Dublin and twice in the Tower, his escapes having been, even in his own eyes, little short of miracles. There is a letter of Creagh’s extant in which he complains that he was in such poverty in the Tower that he could neither by night nor day change his shirt, not having one penny of his own or from any other to pay for the washing of the “broken shirt that is on my back, besides the misery of cold without gown or convenient hose.” He died in the Tower in 1585.