James II’s Irish Campaign

As a military adventure the stay of James in Ireland was not creditable to a man who had served in three campaigns with the great Turenne, fought against Conde and Spain, and been Admiral of the Fleet in England. In watching his Irish campaign we are gripped by the same sense of unreality which pervades much of the course of the Confederate Wars.

The irresolution of the King and of Tyrconnel, the treacheries of the French generals, the jealousies of the leaders, and the blunders or faithlessness of many of the officers are severely criticized by the Jacobite Colonel, Charles O’Kelly, who describes the campaigns through which he fought on the side of the King in Ireland. The conclusion to which he comes is that the errors of James proceeded “from a wrong maxim of State” which many believed he took, namely, “that the only way to recover England was to lose Ireland.”[1] He was persuaded that England, being chiefly afraid of Ireland as a Catholic stronghold, would immediately recall him when his French and Irish armies were well beaten.

“This grand design,” however, not being of a nature to commend itself to “le Grand Monarque,” who had poured out money on behalf of his ally, James took a less conspicuous way; he determined that as soon as possible the French minister, Count d’Avaux, who had been sent with him to report to Louis XIV the progress of events,[2] and also the French general, de Rosen, should be removed out of Ireland.

A campaign in which the main object of the commanders was to lose the war, and in which the prime purpose of the King was to cashier his generals, becomes uninteresting. James had everything in his favour when he landed. William had not expected this move and was caught unprepared; it was more than a year before he could be ready to cross to Ireland.

The whole of the country owned the authority of James except the towns of Enniskillen and Derry, which were practically English Protestant strongholds, but James firmly believed that he had only to show himself before their walls to recall these Englishmen to their obedience, and “to protect them from the ill-treatment which he apprehended they might receive from the Irish.” He therefore posted straight to Derry, which was surrounded by an army chiefly composed of Rapparees with a thousand regulars under General Hamilton, and summoned the garrison to surrender. It seemed likely that they might consent, for the city was in a state of confusion and without a leader; but the appointment of Major Baker and of the vigorous and war-like George Walker, Rector of Donaghmore, to be Governors, decided the citizens on resistance, and the appearance of King James was greeted with fierce cries of “No surrender,” while a chance volley fired from a bastion struck down the officer riding beside him. The whole place became a hive of industry, every citizen taking his part in the defence of the town, which, weak as it was and crowded with refugees, made a gallant defence and for nearly four months sustained all the horrors of a close siege.[3]

The actual siege began on April 19, 1689, and it was not until July 31 that the besieging army, foiled at last, marched away towards Strabane. The city had been invested for 103 days, and had refused every offer of King James, though they had lost from disease, hunger, and wounds 10,361 persons, and had been reduced to the utmost extremities of want. On the other side, the investing army had lost before the walls a hundred officers and over eight thousand men.

The incidents of the siege are well known. The weakness of Lundy, the Commander-in-Chief, and his attempt to betray the city to James, the erecting of the boom across the Foyle to prevent relief by sea, and the sailing away of the ships that were bringing food to the famished inhabitants almost reduced them to despair. The sturdy patience with which all sufferings were endured well merit the encomium of Berwick, the natural son of James and one of his youngest commanders, who remarked of his opponents:

“The most desperate expedients of the Irish commanders were defeated by a heroism which has not been surpassed in ancient or modern days.”

The brutal conduct of de Rosen, who proposed to drive in all the Protestant inhabitants of the surrounding districts, that they might die of starvation under the walls within sight of the hungry people within, excited the King’s anger and caused him to press for his recall. “Having done what he did at Londonderry,” James found him incapable henceforth of serving him usefully. De Rosen was equally disliked by Tyrconnel, as being a better general than himself, and he was shortly afterward replaced by the Count de Lauzun, who brought over an army of veteran troops for which Tyrconnel exchanged six thousand half-trained Irish soldiers; these he proposed to send out under the command of Justin MacCarthy, Lord Mountcashel, of whose popularity and skill as an officer the Viceroy had shown himself jealous.

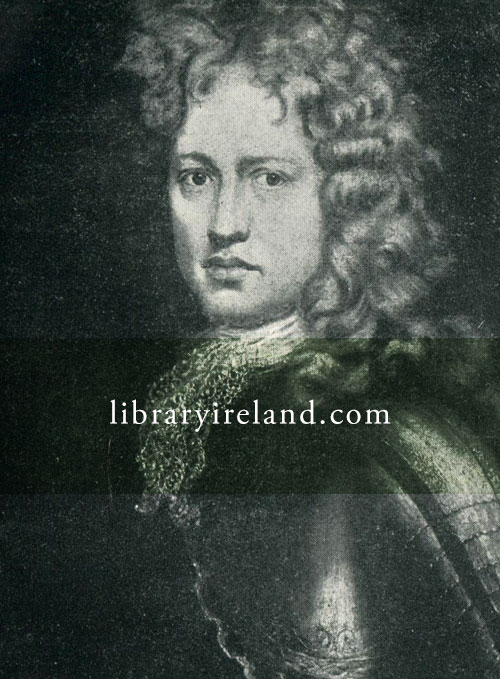

Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan

From the portrait in the Franciscan Monastery, Merchant’s Quay, Dublin.

Misfortune followed James from the first. An attempt to capture Enniskillen was followed by the rout of his troops at Newtown-Butler, owing, it was said, to a mistake in the word of command, which was understood to order a retreat. Mountcashel was captured, and Sarsfield, who here first comes upon the scene, and who had raised by his credit two thousand men in Connacht, was forced to retire to Athlone, leaving the province exposed to the enemy.

Sarsfield was already becoming known as a young captain trusted and beloved by his soldiers, but this was no recommendation to his superiors, who seem to have resolutely held him from any post of honour or responsibility.

Mountcashel escaped from his confinement, but only to find that he was to be sent abroad with the Irish troops. Thus, very early in the war, James lost a capable officer, who was forced by the jealousy of a fellow-countryman to seek in foreign service those laurels for his famous “Mountcashel’s Brigade” which they might have gained at home.

James still had in his army the splendid fighting nucleus of Clare’s dragoons and Dillon’s horse, besides Berwick’s guards and five thousand French foot. But under the irresolute and blundering command of the King and Tyrconnel they proved ineffectual and useless.

The summer passed without any striking military event. But signs that active preparations were being made for the final struggle were visible when, on August 13, 1689, an army of fifteen thousand men landed at Bangor, Co. Down, under the command of the Duke of Schomberg. This veteran of eighty-two years of age had been driven out of France, in which country he had risen to be a Marshal in the army, by the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, after which he took service under William of Orange, now become King of England. He brought over an army composed of many nationalities, which captured Carrickfergus and Charlemont, but during that miserable winter it had no further successes. Set down in camp in Dundalk, the bad food, the moistness of the climate, and the lazy carelessness of the English, who would not build for themselves the necessary shelters, wrought havoc with Schomberg’s fine army. It was fast melting away with disease, lice, and scurvy.[4] The ships and the great hospital in Belfast were crowded with sick men, and between November and the following May over 3,760 were buried from this hospital alone.

Now was the chance for James to strike, but though his army lay not far off the winter passed away, and no move was made. “Our general would not risk anything,” writes the French Dumont, “nor King James venture anything.” James was occupied in Dublin with his Irish Parliament, where his young officers were amusing themselves, “the ladies having expected them with great impatience.”[5]

Tyrconnel was disbanding the troops that should have saved his master’s cause, he having “no great inclination” for the fighting men[6] of which they were composed. Thus the chance was allowed to slip by and on June 14, 1690, William III landed at Carrickfergus and was immediately joined by Schomberg.

Two days later James set out to meet him, resolved, as he had said fully a year before, “not to be tamely walked out of Ireland, but to have one blow for it at least.”[7] He marched north to the passes which divided Ulster from the south, but instead of awaiting William’s advance in this favourable position, he retreated again across the Boyne, drawing up his forces at the Leinster side of the river, apparently with the object of escaping more easily back to Dublin in case of defeat.

Every act of the King showed a painful indecision. He posted a body of foot at the ford of Oldbridge, “not,” as he says in his Memoirs, “that it was to be maintained,” and he sent away his battering engines by night to Dublin, ordering his men to pull down their tents and prepare for a march before the battle began.

These orders, followed by counter-orders, were not calculated to encourage inexperienced troops already dismayed by a retreat and whose only chance lay in the excitement of a vigorous onset. They look suspiciously like a confirmation of O’Kelly’s view that James was not anxious to win the battle. He was at a disadvantage as regards numbers; though the accounts differ. Story and the Jacobite tract “A Light to the Blind” agree in giving the numbers of the Orange troops as 36,000 men, belonging to ten different nationalities, while James had about 20,000 or 23,000, including the French troops, but he had a marked inferiority in arms and guns.

Though the battle of the Boyne is popularly regarded as a struggle between English and Irish, few of William’s English troops took part in the fight; he was doubtful whether their steadiness could be depended upon when they were face to face with their lawful king. And though it is considered as a contest between Protestant and Catholic forces, and is annually celebrated in the North as a Protestant victory, William’s splendid regiment of Blue Guards, which so largely contributed to his success, was chiefly made up of Dutch Catholic soldiers. When James asked them how they could serve on an expedition designed to destroy their own religion one of them replied that “his soul was God’s but his sword belonged to the Prince of Orange.”

As though to complete the contrariness which meets us here, as at every point in Irish history, William’s army marched with sprigs of green in their caps, while the Jacobites wore strips of white paper. The battle, fought on July 1, 1690, (July 12, New Style) centred in the contest for the ford of Oldbridge, which was gallantly maintained by the troops of James.

The enemy had the advantage of the high ground on the north of the Boyne and their line stretched from the fordable shallows of the river toward Slane on their right and in the direction of Drogheda on the left.

In the early morning William narrowly escaped being cut off. He was seated on a grassy slope above the river watching his men as they marched in. His officers, Schomberg, Ormonde, Count Solmes, and others, were around him. On the opposite bank were the Jacobite officers, on horseback, riding by to watch the muster of the Williamite forces. They included Tyrconnel, Sarsfield, Parker, and Lauzun, besides the Duke of Berwick, who, before his twentieth year, had fought in more than one European campaign, and whose bravery was said to be always conspicuous as his conduct was always deficient. They were followed by some dragoons, who, planting two small field-pieces near the river, suddenly let fly a couple of shots, one of which grazed William’s shoulder just as he was mounting his horse. The rumour spread, even to Paris, that he was killed; but, making light of the wound, he remained in the saddle till nightfall.

The main encounter was on the following day. A portion of the Williamite army was sent round to the right to capture the fords near Slane, with the intention, if the crossing at Oldbridge could be carried and the army of James forced back, of cutting off his retreat. If this had been done the rout of his army must have been complete.

When the fords of Slane had been secured, in spite of a vigorous defence by Sir Neal O’Neill’s dragoons, the main action was fought out at Oldbridge. Schomberg, in command of the centre, saw his Danes and Huguenots wavering under the fierce attack of the Irish led by Colonel Hamilton. Plunging into the river, the old General cried aloud to his Huguenot followers: “Allons, messieurs, voilà vos persecuteurs.” In the confused mêlée that succeeded these inflammatory words, a band of Irish horse pushed its way through the main body of the enemy, and the old Marshal fell, with two sabre-cuts in his head and a shot through his body.

Dr. Walker, of Derry, fell not far from his commander. But William, riding up and down between his regiments, succeeded in crossing lower down and attacked the Irish on the flank. They only gave way in the late evening after furious fighting.

The news was brought to James in a church at the summit of the Hill of Donore, from which place of safety he had watched the action of his left wing. He ordered a general charge before the ill news should reach the troops beneath him, but Lauzun advised him to take his own regiment of horse and some dragoons and make the best of his way to Dublin, leaving to him the conduct of the retreat.

The King, though he had often complained that all that the French seemed to care for was to get him out of the country, was at last persuaded to take Lauzun’s advice. He arrived in Dublin that night. Lady Tyrconnel, as she received James at the Castle gate and conducted him up the staircase, asked what his Majesty would take for supper. He replied by explaining what a breakfast he had got, which made him have but little stomach for his supper. Next morning, sending for the Mayor and sheriffs, he told them that in England he had an army which durst have fought, but they proved false and deserted him; and that here he had an army which was loyal enough, but would not stand by him.[8]

Lauzun followed the King’s leisurely retreat along the Irish coast and hurried him out of the country. James himself was the first to announce to the French Court the news of his defeat. Berwick says that the French officers, in coming to Ireland, “had but three objects in view: to get there, to fight, and to return.” They undoubtedly felt that the quickest way to accomplish their third object was to send the King off before them.