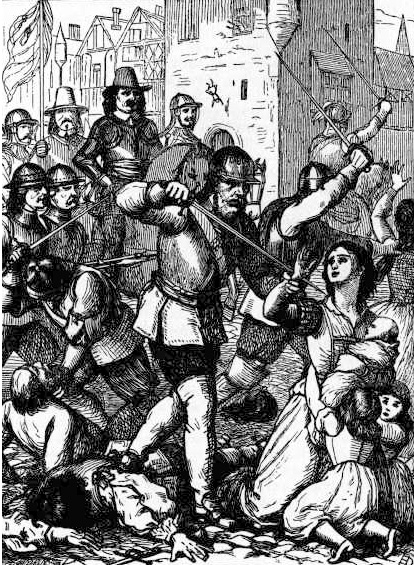

Massacre at Drogheda

Ormonde had garrisoned Drogheda with 3,000 of his choicest troops. They were partly English, and were commanded by a brave loyalist, Sir Arthur Aston. This was really the most important town in Ireland; and Cromwell, whose skill as a military general cannot be disputed, at once determined to lay siege to it. He encamped before the devoted city on the 2nd of September, and in a few days had his siege guns posted on the hill shown in the accompanying illustration, and still known as Cromwell's Fort. Two breaches were made on the 10th, and he sent in his storming parties about five o'clock in the evening. Earthworks had been thrown up inside, and the garrison resisted with undiminished bravery. The besieged at last wavered; quarter [8] was promised to them, and they yielded; but the promise came from men who knew neither how to keep faith or to show mercy. The brave Governor, Sir Arthur Aston, retired with his staff to an old mill on an eminence, but they were disarmed and slain in cold blood. The officers and soldiers were first exterminated, and then men, women, and children were put to the sword. The butchery occupied five entire days: Cromwell has himself described the scene, and glories in his cruelty. Another eyewitness, an officer in his army, has described it also, but with some faint touch of remorse.

Massacre at Drogheda

A number of the townspeople fled for safety to St. Peter's Church, on the north side of the city, but every one of them was murdered, all defenceless and unarmed as they were; others took refuge in the church steeple, but it was of wood, and Cromwell himself gave orders that it should be set on fire, and those who attempted to escape the flames were piked. The principal ladies of the city had sheltered themselves in the crypts. It might have been supposed that this precaution should be unnecessary, or, at least, that English officers would respect their sex; but, alas for common humanity! it was not so. When the slaughter had been accomplished above, it was continued below.

Neither youth nor beauty was spared. Thomas Wood, who was one of these officers, and brother to Anthony Wood, the Oxford historian, says he found in these vaults "the flower and choicest of the women and ladies belonging to the town; amongst whom, a most handsome virgin, arrayed in costly and gorgeous apparel, kneeled down to him with tears and prayers to save her life." Touched by her beauty and her entreaties, he attempted to save her, and took her out of the church; but even his protection could not save her. A soldier thrust his sword into her body; and the officer, recovering from his momentary fit of compassion, "flung her down over the rocks," according to his own account, but first took care to possess himself of her money and jewels. This officer also mentions that the soldiers were in the habit of taking up a child, and using it as a buckler, when they wished to ascend the lofts and galleries of the church, to save themselves from being shot or brained. It is an evidence that they knew their victims to be less cruel than themselves, or the expedient would not have been found to answer.

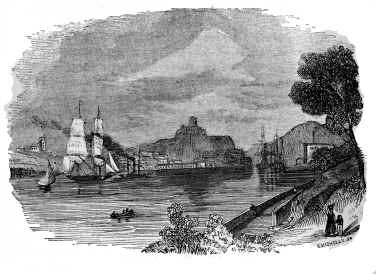

Cromwell's Fort, Drogheda

Cromwell wrote an account of this massacre to the "Council of State." His letters, as his admiring editor observes, "tell their own tale;"[9] and unquestionably that tale plainly intimates that whether the Republican General were hypocrite or fanatic—and it is probable he was a compound of both—he certainly, on his own showing, was little less than a demon of cruelty. Cromwell writes thus: "It hath pleased God to bless our endeavours at Drogheda. After battery we stormed it. The enemy were about 3,000 strong in the town. They made a stout resistance. I believe we put to the sword the whole number of defendants. I do not think thirty of the whole number escaped with their lives. Those that did are in safe custody for the Barbadoes. This hath been a marvellous great mercy." In another letter he says that this "great thing" was done "by the Spirit of God."

Notes

[8] Quarter.—Cromwell says, in his letters, that quarter was not promised; Leland and Carte say that it was.

[9] Tale.—Cromwell's Letters and Speeches, vol. i. p. 456. The simplicity with which Carlyle attempts to avert the just indignation of the Irish, by saying that the garrison "consisted mostly of Englishmen," coupled with his complacent impression that eccentric phrases can excuse crime, would be almost amusing were it not that he admits himself to be as cruel as his hero.—vol. i. p. 453. A man who can write thus is past criticism. If the garrison did consist mainly of Englishmen, what becomes of the plea, that this barbarity was a just vengeance upon the Irish for the "massacre."