St. Patrick’s Pilgrimages

PATRICIAN PILGRIMAGES

Croagh Patrick, from the sea, 2510 feet

It may be well to say a few words concerning the PILGRIMAGE itself. It is hardly necessary to observe that pilgrimages of this kind, for the purpose of visiting in a spirit of faith and penance holy places, sanctified by the penance and by the labours of our Saviour and His Saints, have been in use from the earliest days of Christianity, and will continue to the end of time. They are the natural outcome of Christian piety, and they have always proved to be a most efficacious means of enlivening Christian faith and deepening Christian devotion. Pilgrimages to the sacred scenes in the Holy Land were made long before the time of St. Helena, and, one way or another, are still made every year by members of every Church that calls itself Christian.

In Ireland, too, such pilgrimages have been made from the beginning, and not unnaturally to the places most intimately associated with the life and labours of St. Patrick. Of those, four stand out as the most celebrated —those of Armagh, Downpatrick, Lough Derg, and the Reek; and for many centuries the two last have been by far the most frequented places of penance and devotion. This is not the place to speak of Lough Derg, the most famous place of pilgrimage in the North of Ireland, and if we do not except the Reek, the most celebrated in all Ireland.

PILGRIMAGE TO THE REEK

Pilgrims surrounding the Oratory on the summit of Crough Patrick

Now we find the pilgrimage to the Reek existing from the very beginning. The ancient road by which the pilgrims crossed over the hills from Aghagower to the Reek can still be traced, worn bare, as it were, by the feet of so many generations of Patrick’s spiritual children. No doubt the celebrity and sanctity of the place in popular estimation arose not only from the fact that St. Patrick prayed and fasted there for forty days, and blessed the hill itself, and the people, and all the land from its summit, but also from the promise of pardon said to be made in favour of all those who performed the pilgrimage in a true spirit of penance. In the Tripartite Life the first privilege St. Patrick is said to have asked and obtained from God, is that any of the Irish who did penance even in his last hour would escape the fire of hell. That is, no doubt, perfectly true, if there be real penance; but in popular estimation it came to mean that penance at the Reek was an almost certain means of salvation, through the influence of the prayers, example, and merits of Patrick. Moreover, if any sinners were likely to obtain the special favour of the Saint, it would be those who trod in his sacred footsteps, praying and enduring, where he himself had prayed and endured so much. This is a perfectly sound and just view.

Penance—sincere penance—performed anywhere will wash away sin, even in the latest hour of a man’s life; but the penance is far more likely to be sincere, and the graces from which it springs are far more likely to be given abundantly, in the midst of those places which Patrick sanctified, and through the efficacy of his intercession for such devoted disciples. He prayed for all the souls of Erin; but naturally enough, he prays especially for those who honour, and love, and trust him. On the soundest theological principles, therefore, a pilgrimage to the Reek is likely to be a most efficacious means of obtaining mercy and pardon through the prayers and merits and blessings of Patrick. And Colgan tells us, in a note to the promise referred to above, that the Reek was constantly visited by pious pilgrimages with great devotion, from all parts of the Kingdom, and many miracles used to be wrought there. That was some three hundred years ago. But the pilgrimage was an old one many centuries before the time of Colgan, for Jocelyn tells us in the twelfth century that crowds of people were in the habit of watching and fasting on the summit of the Reek, believing confidently that by so doing they would never enter the gates of hell, for “that privilege was obtained from God by the prayers and merits of St. Patrick”—and that hope is, no doubt, the chief motive of the pilgrimage. Even in those ancient days it was considered a great crime to molest any persons on their way to the Reek; and we are told in the Annals of Lough Ce that King Hugh O’Connor cut off the hands and feet of a highwayman who sought to rob one of the pilgrims. Sometimes, too, the pilgrims suffered greatly, like St. Patrick, not only on their journey thither, but on the Reek itself. St. Patrick’s Day also being within Lent was a favourite day for the pilgrimage, and we are told in the Annals “that thirty of the fasting folk” perished in a thunder storm on the mountain in the year A.D. 1113, on the night of the 17th of March. But like those who die in Jerusalem on pilgrimage, no doubt their lot was considered a happy one.

It was doubtless the hardships and dangers attendant on the pilgrimage to such a steep and lofty mountain that induced the late Archbishop, Most Rev. Dr. MacEvilly, to apply to the Pope for authority to change the place of pilgrimage to some more convenient spot. The petition was granted on the 27th May, 1883, and at the same time a plenary indulgence was granted on any day during the three summer months to all who would visit the church designated by the Ordinary; and a partial indulgence of 100 days for every single visit paid to that church during the three months named—June, July, and August. There is nothing, I believe, to prevent the Ordinary still “designating” the little oratory on the summit of the mountain, and I did so last Summer, as you know, with very wonderful results. I should not wish to see this ancient pilgrimage discontinued. I know His Eminence Cardinal Moran is of the same mind. Moreover, it is practically impossible to transfer the scene of such pilgrimages to other places, and so it has proved here. The blessing of God and Patrick has been on the ancient pilgrimage, and on the pilgrims too. It will be with them still, and, for my part, I shall authorise the celebration to take place every year on the very summit of the Reek; and I believe it will bring graces and blessings to all those who ascend in fact and make the pilgrimage, or if they cannot ascend in fact, will ascend in spirit with the pilgrims to pray on Patrick’s Holy Mountain.

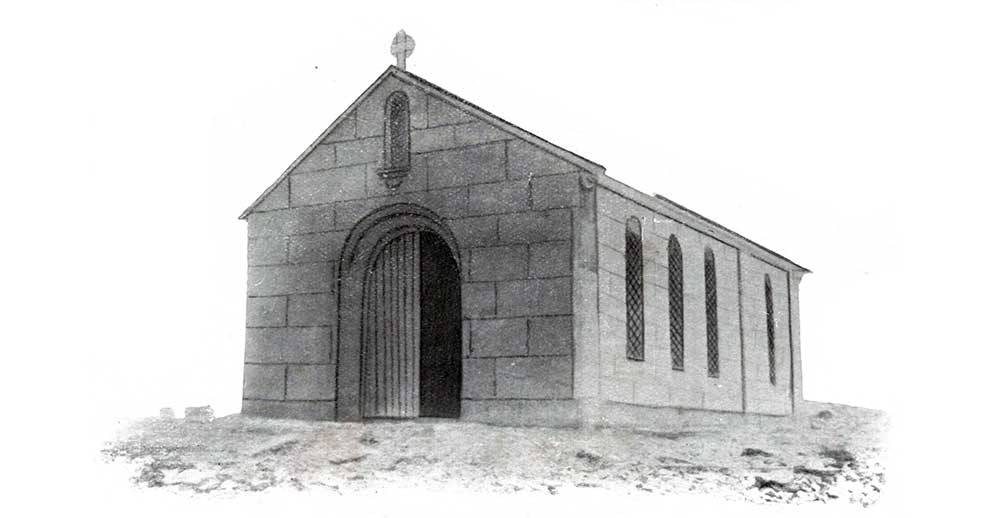

Oratory on Croagh Patrick

I can say for myself that the vision of this sacred hill has been constantly before my mind for many years during all my Irish studies. I have come to love the Reek with a kind of personal love, not merely on account of its graceful symmetry and soaring pride, but also because it is Patrick’s Holy Mountain—the scene of his penance and of his passionate yearning prayers for our fathers and for us. It is to me, moreover, the symbol of Ireland’s enduring Faith; and, fronting the stormy west unchanged and unchangeable, it is also the symbol of the constancy and success with which the Irish people faced the storms of persecution during many woeful centuries. It is the proudest and the most beautiful of the everlasting hills that are the crown and glory of this western land of ours. When the skies are clear and the soaring cone can be seen in its own solitary grandeur, no eye will turn to gaze upon it without delight—even when the rain clouds shroud its brow we know that it is still there, and that when the storms have swept over it, it will reveal itself once more in all its calm beauty and majestic strength. It is, therefore, the fitting type of Ireland’s Faith, and of Ireland’s Nationhood, which nothing has ever shaken, and with God’s blessing nothing can ever destroy.