Grania Uaile (Grace O'Malley) widowed and in rebellion

CARRIGAHOWLEY CASTLE

Grania was not long returned from her Dublin prison when she began again to raid her neighbours from her castle of Carrigahowley, whereupon Captain William Martin was sent with a strong body of troops by sea to besiege the castle. This was in 1579. They set out on the 8th March, and spent three weeks before the castle, but the gallant Grania beat them off, and was very nearly capturing the whole band.

There is probably, we may infer from this, some truth in the popular tradition that Grania held the castle for herself, and sometimes drove away even her own husband from its walls. The castle was finely situated on the bank of a small stream at the very head of the Bay, so that at high water the tide flowed over the rock on which it stood, and lapped its very walls.

If Grania was hard pressed on the land side, she could easily escape by sea, and retreat to Clare Island or elsewhere. And if pursued closely on sea, she could retreat to her castle, from which the foe would keep a respectful distance, for it was protected by heavy guns mounted on its battlements, which her devoted clansmen knew well how to use, as Captain Martin learned to his cost.

GRANIA POLITIC

Yet Grania was politic, and was always ready to pay her respects in person, and yield fitting obedience to the Deputy or his Governors.

Sir Nicholas Malby, the Governor before Bingham, came down here to Westport, and put up at the Castle of “Ballyknock,” which I take to be the old castle of Baun, near Pigeon Point.

Iron Richard was in trouble at the time, and fled to some of the islands, where the Governor could not reach him, but Grania with some of her kinsmen visited Malby, promised all submission and obedience, and got off both herself and her husband with flying colours.

Two years later, in October, 1582, the same Sir Nicholas Malby writes that “McWilliam (her husband) and many other gentlemen and their wives, amongst whom is Grania O’Malley, who thinketh herself no small lady, are at present assembled to make a plot for continuing the quietness.” Malby was a kind-hearted Governor, and they were not disposed to cause him much trouble.

Next year Theobald Dillon went down to Tirawley to collect the Government rents which McWilliam had agreed to pay when he was knighted. “McWilliam,” Dillon says, “and his wife, Grania ni Maille, met me with all their forces, and did swear that they would have my life for coming so far into their country, and especially his wife would have fought with me before she was half a mile near me.” They yielded, however, when they saw the 150 horse with Dillon, and gave him his rent and also 30 beeves, with other provisions, for the soldiers.

Moreover, McWilliam and Grania both went off to meet Sir Nicholas, and agreed to pay him the £600 arrears due upon their country, which, adds the writer, “they had never thought to pay.”

Small blame to Grania to evade payment if she could; but she was as politic as she was brave, and was always ready to temporise in presence of a power superior to her own—and, in my opinion, she was quite right.

AGAIN A WIDOW

It would appear that Iron Richard, Grania’s second husband, died in 1583, and was succeeded as McWilliam by another Richard Burke, described as “of Newtown” in Tirawley.

Grania was now a second time a widow, and, as she bitterly complained seven years later, got no share of the lands of either of her late husbands, “as by the customs of the country the widow was entitled to nothing but the restitution of her dower,” which very often could not be recovered at all, because the dower itself was spent, and the security for its repayment was worthless.

But she was by no means without resources. Her sons of the second marriage, to whom she appears to have been greatly devoted, were doubtless at this period at fosterage with some of the Burkes, and caused her no anxiety or expense.

The eldest son was called Theobald or Tibbot na Long, so called because he was born at sea, perhaps during one of his mother’s many raids in the western seas. It would appear that later on his mother brought the youth to London to visit the Queen, and also with the hope of procuring a peerage for him—for was he not as good a Burke as the Earl of Clanrickard, or any of the peers of the Pale? And as a fact the peerage was conferred at a later date, not, however, by Elizabeth, but by Charles I., when Tibbot of the Ship became first Viscount Mayo, the ancestor of an illustrious but unfortunate line.

GRANIA IN REBELLION

Grania being again a widow was once more free to set up at her old trade, and lost no time in doing so. It would appear she now made Carrigahowley her headquarters.

The cruelty and greed of Sir Richard Bingham drove the Mayo Burkes into rebellion in 1586; and the murder of her eldest son, already described, caused Grania to give her sympathies, and, to some extent, her help to the rebels.

Her own statement is that after the death of her last husband “she gathered together all her own followers, and with 1,000 head of cows and mares she departed” (no doubt from her husband’s residence), “and became a dweller in Carrigahowley at Burrishoole, parcel of the Earl of Ormond’s lands in Connaught (which she or her late husband rented from him). After the murdering of her son Owen, the rebellion being then in Connaught, Sir Richard Bingham granted her letters of protection against all men, and willed her to remove from her late dwelling at Burrishoole, and come and dwell under him (somewhere near Donomona or Castlebar). In her journey as she travelled she was encountered by five bands of soldiers under the leading of John Bingham (who had already caused her son to be murdered), and thereupon she was apprehended and tied with a rope—both she and her followers; at the same instant they were spoiled of their said cattle, and of all that they ever had besides the same, and brought to Sir Richard, who caused a new pair of gallows to be made for her last funeral, when he thought to end her days; but she was set at liberty on the hostage and pledge of one Richard Burke, otherwise called the ‘Devil’s Hook’—that is, Richard of Corraun, her own son-in-law.”

“When she did rebel,” she adds, “fear compelled her to fly by sea to Ulster, and there with O’Neill and O’Donnell she stayed three months, her galleys in the meantime having been broken by a storm. She returned then to Connaught, and in Dublin received her Majesty’s gracious pardon through Sir John Perrott, six years ago, and was so made free. Ever since she dwelleth in Connaught, a farmer’s life, very poor, bearing cess, and paying her Majesty’s composition rent, having utterly given over her former trade of maintenance by land and sea.”

This was written in July, 1593, when Grania must have been well over sixty years of age; nevertheless, she wrote a letter later on to Burghley asking him to procure “her Majesty’s letter under her hand authorising her to pursue during her life all her Majesty’s enemies by land and sea.” This was, no doubt, a bit of a bounce for the old widow, who merely meant to gain favour with Elizabeth. We do not know the year of her death. It was probably about the time that Elizabeth herself died, in 1603.

There are three points connected with the history of Grania Uaile which are more open to discussion than any of the afore-mentioned authentic incidents, and these are: (1) How far was she responsible for the murder of any of the shipwrecked Spaniards of the Armada cast away in Clew Bay? (2) Did she really visit Queen Elizabeth at Hampton Court? (3) Did she really carry off the heir of St. Laurence of Howth, and restore him only on conditions?

THE WRECK OF THE ARMADA

With reference to the first point, I can find no indications in the State Papers that Grania in any way maltreated the shipwrecked Spaniards, or handed them over to be butchered by Bingham.

We are told by an eyewitness that one great ship was cast away in the estuary of the Moy near Killala; 72 of her crew were taken prisoners by William Burke of Ardnaree, who treated them badly; most of the rest were either slain or drowned; and one cruel savage, Melaughlen Mac an Abb by name, boasted that he killed 80 of the shipwrecked men with his own axe.

Another ship was driven ashore at Ballycroy, where her crew, to the number of 400 or 600 men, began to fortify themselves apparently in the Castle of Doona; but they were taken off by one of their own ships shortly afterwards.

Another great ship was wrecked on Clare Island; 68 of her crew were drowned or slain, “probably after landing, by Dubhdaire O’Malley, chief of the island, and his followers.”

The author of A Queen of Men makes this Dubhdaire Roe a nephew of Grania, which is probable enough; but Grania herself appears to have had nothing whatever to do with this abominable crime; nor does it appear that she was on the island at the time.

Another account says that Don Pedro de Mendosa and 700 men were drowned in that wreck off Clare Island, and that Dubhdaire Roe O’Malley put, not 60, but 100 of the survivors to the sword.

Comerford, the Attorney-General of Connaught, on September 13th wrote to Bingham that he stayed within view of another great ship at Pollilly by Torane, that her consort was wrecked and waterlogged close by, but the great ship after some delay took off her crew, and made sail to the south-west, having on board, it appears, the greatest man on the expedition, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the first noble of Spain, who succeeded in reaching Santander. The ship that grounded had on board, he adds, a store of great pieces—guns and other munitions—with wine and oil.

This Torane appears to be the townland of Tooreen near the Old Head, and it would appear that the Duke’s great ship was able to ride out the fierce storm of September 10th under shelter of the Old Head. No word of Grania here except one that would imply that she helped the Spaniards, not yet at Burrishoole, where two more of the Spanish ships were wrecked on the sand banks, and their crews either drowned or reserved for Bingham’s shambles ashore. He caused 200 shipwrecked prisoners taken in Connemara to be butchered in Galway in one day, Saturday, and he rested on Sunday, “giving thanks to Almighty God for our deliverance.”

THE VISIT TO LONDON

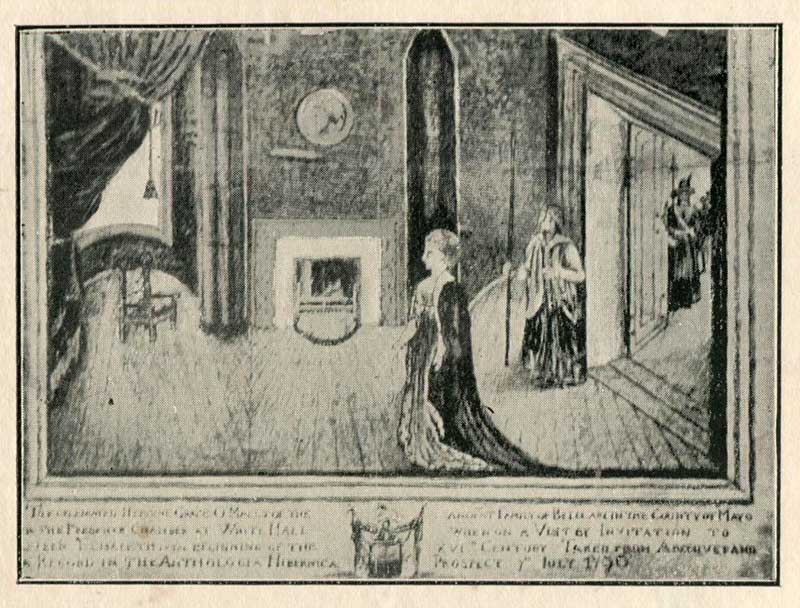

Grania Uaile (Grace O'Malley) before Queen Elizabeth

It is quite clear from the State Papers, although not expressly stated, that Grania did visit London, and had an interview with Queen Elizabeth, probably in 1593.

In July of that year she had petitioned the Queen and Burghley for maintenance, and begged the Minister to accept the surrender of her sons’ lands—that is her sons by both husbands—and grant them a patent for their lands on surrender.

She also asked her Majesty’s license to prosecute all her Majesty’s enemies with fire and sword—a bold demand for an old lady over sixty, with sons and grandsons; but she knew it would please the Queen, and if granted would give her once more a free hand on the western coasts.

It was at this very time that Bingham, in a letter to the Privy Council, describes Grania as “a notable traitress, and the nurse of all the rebellions in the province for forty years.”

Grania renewed her petition to Burghley two years later (in 1595), “to be put in quiet possession of a third of the land of both her late husbands.”

She certainly went to London in 1593, in the month of August, as Bingham’s letter of September 19th shows, and if she went to London, no doubt she saw the Queen and her Minister, for nothing else would or could have induced her to go there at all.

Then Elizabeth and her Court would, no doubt, be very glad to see the rival Queen of the West in all her barbaric magnificence, accompanied by her wild attendants apparelled in native style.

Unfortunately we have, so far as I know, no authentic account of this famous interview at Hampton Court. Popular writers, like the Halls, give free reign to their imagination in describing it, but it is all pure imagination.

The two queens at this time were about the same age, and neither of them could be vain of her personal charms, for both were in the sere and yellow leaf.

We may be sure they eyed each other with great curiosity, and took wondering note of each other’s queenly raiment. The dialogue, too, must have been interesting, though doubtless carried on through an interpreter, for as Grania’s husband, the late McWilliam knew no English, but was well skilled in Latin and Irish, we may fairly conclude that Grania, too, had no Beurla.

There is reason to think that the English Queen granted Grania her requests, and sent her home rejoicing.