The Four Masters (2)

That school at Kilbarron flourished during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, down to the flight of the Earls, in A.D. 1607, when, as you know, the old proprietors were all expropriated in Donegal, as well as in five other counties of the north; and the ample domains of the O’Clerys of Kilbarron became the spoil of the stranger, and that ancient sanctuary of Celtic learning was left a desolate and dismantled ruin. Now, this brings us down to the time of the Four Masters; and we must pass from Kilbarron to Donegal Abbey. It is not a long way—as the bird flies, about seven miles—over the sand-hills, and down by the sea, that far-sounding sea, where the broken billows roar in a fashion that old Homer never heard, past the old abbey of Drumhome, where we have good grounds for believing that two Irish scholars, whose names are known throughout all Europe, spent their youth: that is, Adamnan, the biographer of St. Columba, and the blessed Marianus Scotus, the Commentator.

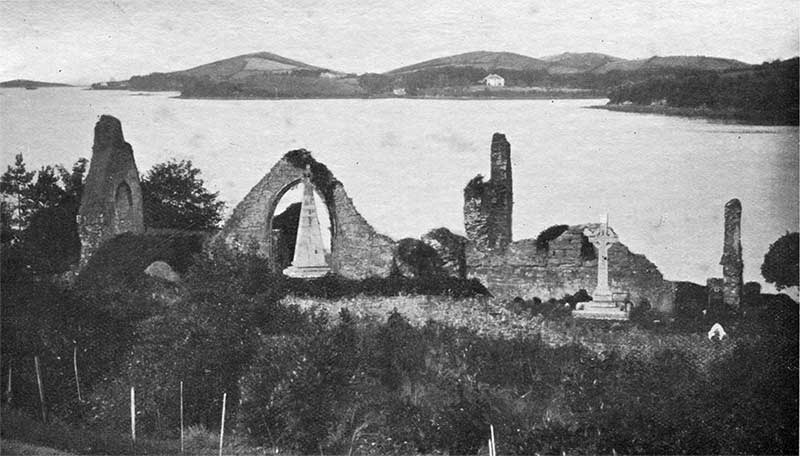

Presently the bay narrows and becomes like a broad river, flowing between fertile and well-wooded banks, especially on the northern shore; and then you suddenly come upon the old abbey, standing close to the water’s edge at the very head of the bay. Little now remains of the building—the eastern gable, with a once beautiful window, from which the mullions have been torn down; a portion of the stone-roofed store-rooms, and one or two of the cloister arches, with their broken columns—that is all that now remains of the celebrated Franciscan Abbey of Donegal. Still, it is a ruin that no Irishman should pass heedless by; not so much for what he will see, as for what he must feel when standing on that holy ground, so dear to every cultivated and thoughtful mind.

Donegal Abbey

“Many altars are in Banba,

Many chancels hung in white,

Many schools and many abbeys

Glorious in our fathers’ sight;

Yet! whene’er I go a pilgrim

Back, dear Holy Isle, to thee,

May my filial footsteps bear me

To that abbey by the sea—

To that abbey, roofless, doorless,

Shrineless, monkless, though it be.”

It was founded in the year 1474 by the first Hugh Roe O’Donnell and his pious wife, for Franciscans of the Strict Observance. Under the fostering care of the O’Donnells, whose principal castle of Donegal was close at hand, the abbey in a short time grew into a great and flourishing house, and became the religious centre of all Tirconnell, although Abbey Assaroe still survived in almost undiminished splendour on the banks of the Erne. The despoiling edicts of Henry VIII. did not run in Tirhugh. Hence we find that when Sir Henry Sydney, the deputy, visited Donegal, in 1566, he described the abbey as “then unspoiled or unhurt,” and, with a soldier’s eye, he perceived that it was, “with small cost fortifiable, much accommodated, too, with the nearness of the water, and with fine groves, orchards, and gardens, which are about the same.” Close at hand there was a landing-place, so that when the tide was in, foreign barques, freighted with the wines of Spain and silks of France, might land their cargoes at the convent walls, and carry away in exchange Irish hides, fleeces, flax, linen, and cloth. So we are expressly told by Father Mooney, who must have often seen the foreign ships when he was a boy, and who tells us also that in the year 1600 there were forty religious in the community, and forty suits of vestments of silk and cloth of gold in the sacristy, with sixteen chalices and two ciboriums. But in that very year the traitor Nial Garve O’Donnell seized on the abbey, in the absence of his chief, and held it for the English. By some accident, however, the magazine blew up on Saturday, the 2oth of September, at early dawn, and the beautiful fabric was almost entirely destroyed.

After the battle of Kinsale and the flight of the Earls it passed into Protestant hands, and was partially restored, so that Montgomery, the King’s Bishop of Raphoe, proposed to make it a college for the education and perversion of the young men of the north who could not afford to go to Trinity College. This benevolent proposal was not adopted by King James; but about the beginning of the reign of King Charles, when some measure of toleration was granted to the Catholics, the building, probably then derelict, seems to have again been occupied by the Franciscans. This I infer from the express statement of Brother Michael O’Clery himself, as well as from that of the superiors of the convent, who declare that the Annals of the Four Masters “were begun on the 22nd day of the month of January, A.D. 1632, in their convent of Donegal;” and that “they were finished in the same convent of Donegal on the 10th day of August, A.D. 1636, the eleventh of the reign of King Charles.” Colgan also distinctly asserts that they “were completed in our convent of Donegal.”

Let us now go back to that Tuesday, the 22nd January. in the year 1632. It was truly a memorable scene, the first session of the Masters in the library of the half-ruined convent of Donegal. We can realise all the details from the statements of the Four Masters themselves, and of the superiors of the Convent of Donegal. Bernardine O’Clery, a brother of Michael O’Clery, was then Guardian of the convent, and most generously undertook, with the assent of his poor community, to supply the Masters with food and attendance gratuitously during the entire period of their labours. He placed the convent and everything in it at their disposal, so far as was necessary for their comfort and convenience. The library, as Sir James Ware tells us, was well supplied with books; and there they took their places in due order according to their official rank, for the antiquarians then as now were most jealous of their rights and privileges—all the more so, perhaps, because they were slipping away from them for ever.

Brother Michael took his seat at the head of the table; around him on either side were his venerable colleagues—each with the parchment books of his family and office, which were hardly ever permitted to be taken out of the personal custody of the Ollave, lest they might be in any way injured or mutilated. On his right, we may assume, sat the two Mulconrys—Maurice and Fergus—from Ballymulconry, in the County Roscommon, historical ollaves to O’Connor, and the first authorities in all the historical schools. Maurice explains that he himself cannot remain long with them, but that Fergus would remain throughout, and have the custody of the books of Clan-Mulconry. Hence, Colgan does not reckon this Maurice as one of the Four Masters, although he gave them his assistance for one month. On the left of Brother Michael sat Peregrine O’Duigenan from Castlefore, a small village in the County of Leitrim, near Keadue. He was Ollave to the M‘Dermotts and O’Rorkes, and came of the celebrated family known as the O’Duigenans of Kilronan, because they were erenaghs of that church, as well as ollaves to the chiefs of Moylurg and Conmaicne.

He had before him the great family record known as the Book of the O’Duigenans of Kilronan. Next to him sat Peregrine O’Clery, son of a celebrated scholar, Lughaidh O’Clery, and at this time the head of the family, and the official chief of the ollaves of Tirconnell. In better days, when he was still a boy, during the glorious years of the chieftaincy of Red Hugh, his father owned Kilbarron Castle, with all its wide domains, and sat amongst the noblest at O’Donnell’s board in the Castle of Donegal. But now his castle was dismantled, and his lands were seized by Sir Henry Ffolliott and his followers. He had nothing left but his books, which he tells us in his will he valued more than everything else in the world. Like a true scholar, he would part with everything—castle, lands, and honours—sooner than part with these beloved books that he had now before him on the table. At the foot of the table sat Conary O’Clery, an excellent scholar and scribe, but still not ranking with the official ollaves present. He seems to have been chosen as secretary and attendant to the official historians, and hence is not reckoned by Colgan amongst the Four Masters properly so called.

And now that the Masters are about to begin their labours, Brother Michael explains in brief and touching words the object and purpose of their labours, which was to collect and arrange and illustrate[2] the Annals of Erin, both sacred and profane, from the very dawn of our Island’s history down to their own time.

“For [he said] as you well know, my friends, evil days have come upon us and upon our country; and if this work is not done now these old books of ours that contain the history of our country—of its kings and its warriors, its saints and its scholars—may be lost to posterity, or at least may never be brought together again; and thus a great and irreparable evil would befall our native land. Now, we have here collected together the best and most copious books of Annals that we could find throughout all Ireland, which, as you are well aware, was no easy task to accomplish. We must, therefore, begin with the oldest entries in these ancient books; we must examine them carefully, one by one; we must compare them, and, if need be, correct them; then, as every entry is thus examined and approved of by us, it will be entered by you, Conary O’Clery, in those sheets of parchment, and thus preserved to latest posterity for the glory of God and the honour of Erin.

“The good brothers of this convent, poor as they are themselves, have still undertaken to provide us with food and attendance. There is, alas, no O’Donnell now in Donegal to be our patron and protector; but, as you know, the noble Ferrall O’Gara has promised to give you, my friends, a recompense for your labours that will help to maintain your families at home. As for myself—a poor brother of St. Francis only needs humble fare, and the plain habit of our holy founder. So now let us set to work hard, late and early, with the blessing of God, and leave the future entirely in His hands.”

Yes, let them work for the glory of God and the honour of Erin:—

“We can hear them in their musings,

We can see them as we gaze,

Four meek men around the cresset,

With the scrolls of other days—

Four unwearied scribes who treasure

Every word and every line,

Saving every ancient sentence

As if writ by hands divine.”

Notes

[2] As O’Queely puts it, “colligendo, castigando, illustrando.”