Two Royal Abbeys on the Western Lakes (Cong and Inismaine) - 3

Some eight years later, in A.D. 1135, Cormac McCarthy’s beautiful chapel on the Rock of Cashel was dedicated in the presence of all the kings and nobles of the South. Turlough was determined in his own country to rival and, if possible, excel Cormac M‘Carthy, in architecture as in war. Tuam was burned the same year as Cong, that is, 1137, and, it would appear, by the same Munster raiders; so Turlough determined to rebuild both Abbey Churches on a scale of great magnificence, worthy of the High King of Ireland. And he succeeded. Petrie expressly says thai the chancel arch of the old Cathedral of Tuam, with the east window, which now alone remains, is sufficient to show that “it was not only a larger but a more splendid structure than Cormac’s chapel at Cashel,” and the cloister of Cong shows, too, that there was probably no building in Ireland which excelled in elegance of design and elaborate decoration what the same Petrie calls the “beautiful Abbey of Cong.” Now, I do not say that these buildings were completed so early as 1137, for they would require several years to complete. But I think they were undertaken after the burning of 1137. The two high crosses, one opposite the Town Hall, Tuam, and one that formerly stood near the Abbey of Cong, but of which the broken base now alone remains, were undoubtedly erected to commemorate the completion and dedication of the two Abbeys.

Now, on the base of the cross of Tuam there is an inscription which asks a prayer for King Turlough O’Conor, for the artist Gillachrist O’Toole, for the Comarb of Jarlath, and for Aedh O’Oissin, or O’Hessian, who, in the inscription at the base of the cross, is called “Abbot.” This Aedh O’Hessian became Abbot of Tuam about the year 1128, and continued in that office until the death of Bishop Muireadhach O’Duffy, in 1150, when he himself became at first Bishop, but afterwards Archbishop, on receiving the Pallium at the Synod of Kells. Now, it appears to me clear that the Cathedral was rebuilt while O’Hessian was Abbot, and Muireadhach O’Duffy, Bishop of Tuam, and, therefore, before the year 1150, when O’Hessian succeeded Muireadhach.

The name, “Comarb of Jarlath,” if applied to O’Hessian, does not mean that he was then Bishop of Tuam, for he gets that title in the Annals of Innisfallen so early as 1134, when he was sent by the king on an embassy to Munster. On the base of the high cross of Cong there is a mutilated inscription asking a prayer for Nichol and Gillebert O’Duffy, who was in the Abbacy of Cong. If we could find his date in the Abbacy we might easily know who restored the building, but his name is not mentioned in the Annals. It is highly probable, however, that he was Abbot when his great namesake Muireadhach O’Duffy, Archbishop of Connaught, died at Cong, on St. Brendan’s Day, May 16. The latter is described as “Chief Senior of Ireland in wisdom, in chastity, in the bestowal of jewels and food,” and died at the age of seventy-five, in the new and beautiful Abbey by the Lake.

The Cross of Cong

It is highly probable that O’Duffy had retired to spend the last years of his life with his namesake, and doubtless relative also, at Cong, and that O’Hessian had been his Coadjutor for some years before his death. It is my opinion, therefore, that the beautiful Abbey Churches of Tuam and Cong were both completed between 1137 and 1150, while Turlough was King, and O’Duffy was High Bishop, and O’Hessian was Abbot, who, with Gillebert O’Duffy and O’Toole, all co-operated in the buildings that have given so much lustre to their names and to their country. The great Turlough himself died in Dunmore, and was buried in Clonmacnoise in 1156, “a man full of mercy and charity, hospitality and chivalry”.

These O’Duffys were a great ecclesiastical family, to whom we owe much, but of whom unfortunately we know little, except what we can glean from a few meagre references in the Annals, supplemented in some cases by the inscriptions on the crosses and stones. Yet for more than a century we find them at intervals ruling in all the important religious centres of the West—Clonmacnoise, Tuam, Cong, Mayo, Roscommon, Clonfert, Boyle—each had one or more of the O’Duffy’s in its See, and everywhere, I believe, they have left enduring monuments of their religious zeal and artistic genius.

The great Turlough and his two sons in succession ruled the western province for more than a century, yet, without the O’Duffy’s, I believe, neither Turlough nor Rory nor Cathal O’Conor could have left so many monuments of their own taste and munificence in the cause of religious art and architecture. I am inclined to think that this famous family must have dwelt somewhere in the neighbourhood of Cong or of Tuam—it is not easy to say which. The first of them we hear of was a professor in Tuam and Abbot of Roscommon. Certainly the greatest of them, Muireadhach and Cathal O’Duffy, both High Bishops of Tuam, retired from Tuam to spend the closing years of their lives in the beautiful Abbey by the Lake—there they loved to live, and there they chose to die.

There is another striking trait in their character, and that is their unswerving loyalty and devotion to the O’Conor Kings through good and ill. It is something to praise in a cruel and treacherous time. Little can be said in favour of some of those O’Conor princes—faithless, pitiless, licentious, traitors to father and family and country. Turlough put out the eyes of one of his own sons for his treasons, and Rory, the last king, did the same to one of his sons, the traitor Murtogh O’Conor, who first allied himself with the Normans and led them across the Shannon, hither even to the very streets of Tuam, which the people fired rather than allow to be a resting-place for the foe. Even Cathal the Red-handed, one of the best of them, allied himself again and again with William Burke and the Normans, and brought them to Cong itself and Tuam in 1202, from which they pillaged all the country round about them.

Yet the O’Duffy’s were always loyal to these false kings, and when Rory at length, in 1175, gave up his claim to the throne of Ireland, it was Cathal O’Duffy, the Archbishop, who, with Laurence O’Toole of Dublin, and the Abbot of Clonfert, went over to London to negotiate a treaty on behalf of the discrowned King with Henry of England; and, at a later period, when Rory, deposed by his own sons and weary of the world, retired to spend the last years of his life among the Canons of Cong, doing that penance which he greatly needed, it would appear that Cathal O’Duffy, Archbishop of Tuam for forty years, followed to Cong the aged monarch; that he closed his eyes in death, and then, doubtless, accompanied the body of his beloved but unhappy master all the way to Clonmacnoise, and said the last prayers over his grave, when he was laid to rest beside his noble father, near the altar of Ciaran, in the great Church of Clonmacnoise. Then he, too, weary of the world, returned to Cong to die.

I have called Cong a Royal Abbey, and so in truth it was, for it was founded by a High King, and was rebuilt by kings and by the sons of kings; it was ruled by their closest friends and relations; they loved to live in it and to die in it—both themselves and their kindred.

Let me give a few more facts about the O’Duffys and O’Conors, for while a stone of Cong remains their memory will cling to its mouldering walls. As we have already seen, Muireadhach O’Duffy, who is called Archbishop of Connaught, the greatest, too, of all his family, and, as I take it, practically Prime Minister of King Turlough for nearly thirty years, retired from Tuam to Cong, and died there on the 16th of May, 1150.

He is described as “Senior of Erin” on the Cross of Cong; as “Archbishop of Connaught” by the Four Masters, and as the “Head of Religion in the Chronicon Scotorum. The eulogy pronounced on him by the Four Masters shows that he was regarded as the foremost of the Irish ecclesiastics at the time, “Chief Senior of all Ireland in wisdom, in chastity, and in the bestowal of jewels and food.” He died at Cong, and is buried in Cong. I could wish we knew exactly where, for I have a great reverence for the man’s memory.

In 1168, "Flannagan O’Duffy," whom the Masters describe as "Bishop (of Elphin) and chief doctor of the Irish in literature, history and poetry, and in every kind of science known to man in his time, died in the bed of Muireadhach O’Duffy at Cong." Here we have a great scholar who, like the Archbishop of Tuam, left his diocese in his old age, and retired to his beloved monastery at Cong to gain the victory of penance and to prepare for death. He lived in the room at Cong occupied by Archbishop O’Duffy, "and died in his bed." It was doubtless the cell and the bed kept for the archbishops at the Abbey, and it is not unlikely that he was a nephew or near relative of Archbishop Muireadhach.

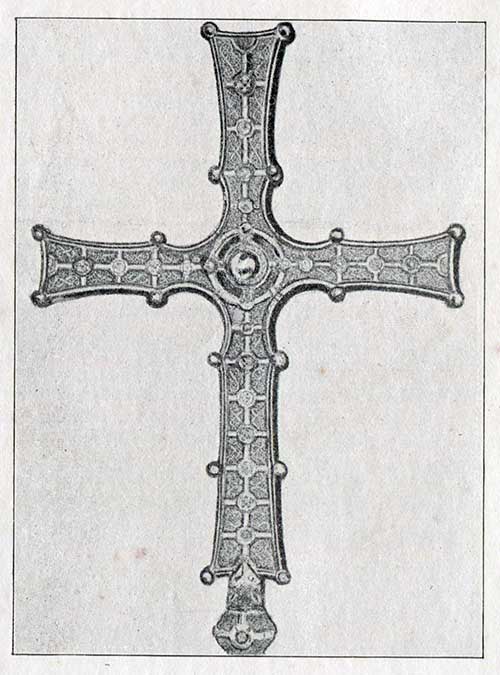

No one in giving an account of Cong can omit all references to the famous Processional Cross of Cong. It was made, the inscription tells us, by Maolisa Oechan for Muireadhach O’Duffy, "Senior of Erin," and for Turlough O’Conor, King of Erin, under the superintendence of Flannagan O’Duffy, Comarb of Coman and Ciaran. It is clear, therefore, it was made for the Church of Tuam, at the expense of Turlough O’Conor, and designed to contain a relic of the True Cross, sent from Rome to Turlough about the year 1123.

It was a work of rare and peerless beauty, and was probably brought for safety sake from Tuam to Cong by Archbishop Muireadhach O’Duffy, for whom it was made, when he retired there to end his life in peace and penance some years before he died in 1150. It was carefully preserved by the Abbots of Cong during all the stormy years that followed, down to the time of Father Prendergast, the last Abbot of Cong, from whom it was purchased in 1839 for the Royal Irish Academy.