Water Supply and Lighting - Story of Belfast

TWO of the most important necessities of our daily life that make for health and comfort are water and light. We have become so accustomed to a plentiful supply of both, that we can scarcely imagine there was once a time when both were regarded as luxuries. For a great number of years, the open river running down the centre of High Street, the mill dams, and various springs and wells about the town sufficed for the supply of the people. In course of time the river became foul and unpleasant, and unfit for use of any kind, more like an open sewer, and every kind of filth was thrown into it. But we must not blame our forefathers too much, for, in those early days, there was no drainage or any means of carrying the waste of the town away, and the open river was there always ready to receive any rubbish. It was convenient, and it was close at hand.

In the year 1678, George McCartney was Sovereign, and we owe a great deal to his wisdom and foresight. He called a town meeting to consider what could be done to obtain a supply of good and wholesome water. It cost two hundred and fifty pounds to bring it in wooden pipes into the town, and three places were arranged where the inhabitants could get water. Of course, it had to be carried into the houses. Lady Donegall gave forty pounds towards this undertaking. This supply continued for many years, and then the pipes wore out, and, when a hard frost came on, the condition of the town was deplorable. Some springs were found to have an abundant supply. The water from Mundy's well in Sandy Row was brought into Fountain Street, and three fountains stood there for the use of poor people. Crowds of women and children were to be seen waiting for their turn at the fountains to fill their buckets and carry home the household supply. Water carts carried Cromac water to the better class houses, where it was sold at a penny for two pails full, and the tinkle of the water bells was heard through the streets. Hot and cold baths were not in great demand.

Holywood was a favourite watering place, and open-air bathing was common all along the shore where the County Down railway runs now. Later on, baths were opened at Lilliput, where Manson taught his pupils swimming.

There were also baths at Bower's Hill in North Street, and a curious arrangement was that each bather received a glass of punch after the bath, all for two shillings. The present Peter's Hill baths would doubtless become immensely popular if a glass of punch were given with every bath, only it would require to be free.

Next we read of a more ambitious effort, for water was conveyed by an open water course from Stranmillis and Malone, and the springs at Fountainville, to a great circular reservoir in a country lane, where trees and fields were round it. It was called the "Basin," and the Basin Lane was once a favourite walk out of the town. It is difficult to realise that Bankmore Street, where Marcus Ward's warehouse was built, is now the only memory of the water supply of early days, and the name of Bankmore lingers about the former reservoir.

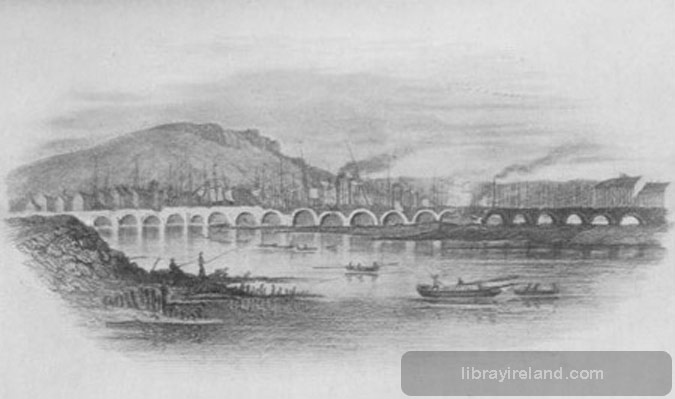

The next improvement in the water supply was under the management of the Charitable Society. Then the next supply came from Solitude and Carr's Glen for the north side of the town, and later on from Woodburn and Carrickfergus. It was brought into the waterworks on Antrim Road, and, still later, from Stoneyford near Lisburn. As Belfast increased with such rapidity, it became necessary to have a much larger supply of water, and so our present water system was carefully thought out and carried to completion. Between Newcastle and Kilkeel, round a spur of Slieve Bingian, and across the river at Kilkeel into the Silent Valley, the river has been impounded and this valley forms one of the sources of Belfast's present water supply. The water is collected from an area 9,000 acres in extent, a reservoir is to be formed by an embankment across the valley, which is 520 yards long and 90 feet high, and the water covers 250 acres. The water is then conducted along the slopes of Slieve Bingian into the valley at Annalong. It flows through a tunnel beneath Slieve Donard and Thomas Mountain, and is carried into Belfast by syphons and conduits. A special reservoir is built 350 feet above the sea level.

When we compare our fine water supply now coming fresh and pure from the Mourne Mountains in an inexhaustible abundance, brought forty miles, we can scarcely imagine how people lived in the old days when they were glad to get it at one penny for two small buckets full. Thirty million gallons will come into Belfast every day when the scheme is completed.

Even more surprising is the change in the lighting of the town. The first attempt was made by a polite request that on very dark nights the householders would place a small candle in their windows to enable travellers to find their way. This illumination was not expected on nights of "Moonshine." It was a usual practice to arrange social entertainments for nights when the moon was visible. In the year 1761, a law was passed that every householder who paid five pounds a year of rent should contribute to place lamps along the river in High Street. This was a wise suggestion, for it must have been a very unsafe place on dark nights. Later on, a law was passed that a "Lanthorn" should be hung on every alternate door or window on dark nights from the hour of six o'clock until ten. All respectable people were supposed to be in their own houses after ten o'clock. This law was to be enforced from twenty-ninth September until twenty-ninth of March. We are not told if the owners of the alternate houses were allowed to use their neighbour's light without any claim for payment. Eight years later, every house was to show a light or pay a fine of sixpence.

After a lapse of many years, when the White Linen Hall was used as a kind of People's Park, and Donegall Place was known as the "Flags," and was the fashionable promenade for the town, the military band performed for two hours in the central vacant place at the entrance gates. Sunday evening was the favourite time. It is natural to suppose that such a gay scene required more extensive illuminations than "Lanthorns " provided, so oil lamps were placed in the iron standards of the railings which enclosed the Linen Hall. An oil lamp burning every twenty yards all round the building made it a pleasant place, and shed a dim religious light over the crowds.

When gas lamps were substituted for the oil, it was considered a great step forward, and so it was, for the gas burned steadily except on the rare occasions of a street riot, when unruly boys thought it was a great joke to smash the lamps and leave the mob in total darkness.

Gas had one great advantage over the oil, for it burned as long as it was required, whereas the oil was an uncertain quantity, and lamps had a bad habit of going out and leaving a smoky wick to perfume the atmosphere with a very doubtful fragrance. It was an exciting evening when the streets were lighted with gas for the first time. The Town Council turned out to see the effect, and the members walked arm in arm along the streets admiring the illuminations and very proud indeed of such a brilliant town.

Now even gas is hiding its diminished radiance in presence of electric light. So we progress step by step, and who can foretell what the generations to come may use to light Belfast in the future? From the open river and the wooden pipes to our magnificent water supply of the present time, and from the small candle stuck in the window-pane to the great globes of light as bright as noon-day, is a wonderful change, and we pause to ask, what will come next?