Thurot's Invasion - Story of Belfast

IT makes a pleasant surprise in one's reading to turn over unexpectedly a page of romantic daring, and to find the story of a gallant young hero just at your own door. An Irish officer named Farrel accompanied James the Second to France, after the Revolution. His grandson, O'Farrel, or Thurot—as he was afterwards named—was born in France. He was early in life left an orphan, and he suffered many hardships. He lived for some time in England, then came to Dublin, lived in Glenarm and Carlingford, and so was very familiar with all the Northern coast of Ireland.

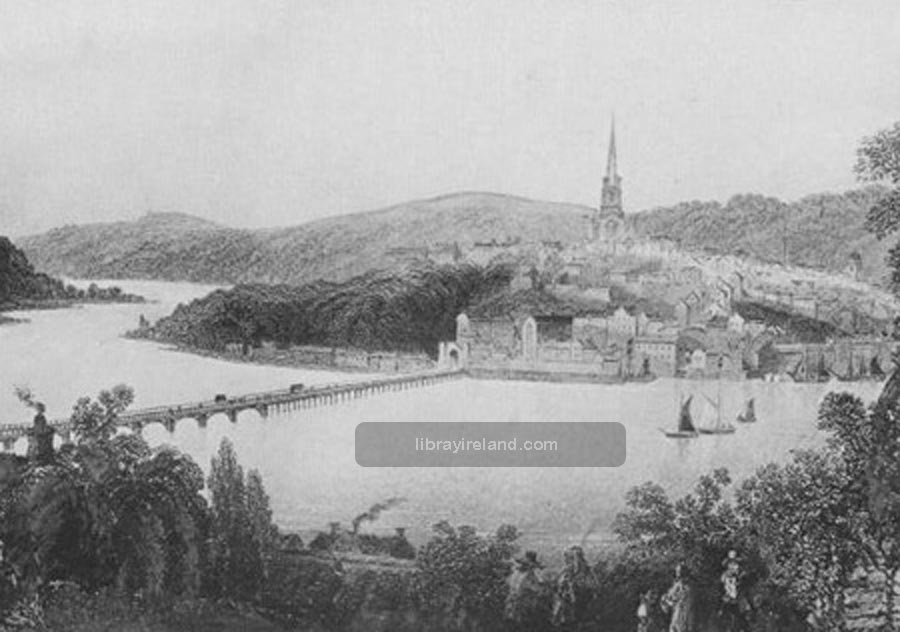

His knowledge of every port and harbour was so accurate that he was chosen by the French Government as the Commander of a squadron. In the year 1759, Commodore Thurot left France with five frigates to invade Ireland, but his enterprise was unfortunate at the outset. The autumnal equinox met his fleet with such severity that one of the frigates returned to France, another was lost to sight and never heard of again, but the courage of the intrepid Thurot kept the remaining three together, even though the storm blew them into theNorth Sea, and he was compelled to spend the winter in Norway and the Orkney Islands. When calmer weather came, he set sail for Ireland, and arrived in Lough Foyle early in the new year. He may perhaps have remembered the history of the " Maiden City," for he wisely made no attempt to molest Derry, but he suddenly appeared before Carrickfergus and boldly demanded its surrender. On the 21st of February, he placed himself at the head of his men and attacked the town. Colonel Jennings was in command of the Castle, which did not possess even one mounted cannon, and the garrison numbered only one hundred and fifty men. There was a brave resistance, but the Castle was obliged to surrender, and the French landed and plundered the town, after levying contributions from the wealthy inhabitants. Thurot took three prisoners, who were afterwards recovered on board his ship.

A touching incident occurred when Thurot landed and advanced with his troops through High Street, and the French men drove the English back. A little child, "Thomas," the son of the Sheriff, John Seeds, ran out of the house, and playfully stood between the conflicting parties. The French officer in command lifted the child in his arms and ran to the nearest door with him, which happened to be his father's, and having placed the child in safety, he then advanced at the head of his men. Forcing one of the gates of the Castle, he was the first to enter, and he was killed between the two gates. He was seen to take a picture from his bosom and died kissing it. He belonged to the noble French family of D'Esterre, and was a remarkably handsome man. Great men have often very tender hearts, and the story of D'Esterre's kindly thoughtfulness for a little child lived long in the history of Carrickfergus. Thurot sent a message to Belfast threatening an attack unless provisions were sent for his men at once. This declaration roused the national spirit of the people, and immense numbers of men poured into Belfast. In twenty-four hours, the town was secure from insult and danger of the French invasion.

A strong barricade was erected at Milewater, and thousands of men armed themselves with weapons, and with Lord Charlemont at the head of his "Defenders," marched to Carrickfergus, while five thousand volunteers remained to protect Belfast. Thurot re-embarked his troops, and his ships were seen lying outside the harbour when Lord Charlemont arrived. The French General Flobert and twenty men were left behind in a wounded condition, and they were afterwards provided with suitable lodgings and assistance. Thurot was met, as he was leaving the Lough, by Captain Elliott, with a squadron of three ships, and, after a sharp action of one hour and a half in the Irish Sea, Thurot was killed and his ships taken into English ports. The French prisoners were brought to Belfast, and kept for three months, when they were sent home in two frigates.

Such a kindly feeling grew on both sides, that great regret was expressed when the time arrived for the Frenchmen to leave. They asked and recived permission to give a ball in the Market House as a token of their gratitude for all the kindness shown to them during their stay. Two hundred ladies and gentlemen attended the farewell ball, and it is recorded as being a scene of "brilliant grandeur."

Indeed, some of the Frenchmen remained behind, no longer as prisoners but as honoured inhabitants of Belfast. So ended the invasion of Carrickfergus. Thurot was a brave man, full of high courage and intrepid daring. He possessed great ability and died fighting for his adopted country, and he was the last to surrender on the deck of his ship. Instead of the fifty thousand pounds he had proudly demanded as a fine from Belfast, he left his dead body as a memento of his ill-fated expedition.

Thurot's gold watch is in the possession of a gentleman near Belfast. It is still in good order and still keeps time.

The story of Paul Jones has been often told, and he figures in many old American books as a hero of romance. Even his enemies had to acknowledge his unfailing courage and his genius. He was born at Kirkcudbright in Scotland, but from a very early age followed the sea, where he made a notorious reputation as a privateer. His line of life would in these days be called by a different name.

A few years after Thurot's ill-fated attempt on Carrickfergus, there was a revolt in the American Colonies, in which France joined with America, and they were united against England. It was a time of great excitement, and many a stirring tale has been written of that long conflict. In April of the year 1778, the famous Paul Jones suddenly appeared in Belfast Lough, with an armed ship called the "Ranger."

A ship, the "Draper," was lying in Garmoyle, laden with a very valuable cargo of linen, and it was thought at first that Jones would attack that ship and take possession of the cargo. But he had more ambitious ideas than to seize a small affair like a load of linen, when a king's ship was within his reach. A sloop of war, the "Drake," was lying off Carrickfergus. He brought his ship into the Lough to attack the man-of-war, but the weather was unfavourable for making the attempt. Paul Jones never was a man to lose much time, so he turned the "Ranger " about and sailed to Whitehaven, where he spiked the guns, burned several ships, and then proceeded to pay a brief but disastrous visit to his native town of Kirkcudbright. He plundered the mansion house of Lord Selkirk, and then returned to Belfast Lough to try and capture the "Drake," which was still lying in Carrickfergus Roads. The two vessels engaged in battle, and after a few hours of determined conflict the "Ranger" was victorious, and Paul Jones conquered and captured the English man-of-war. He left Belfast Lough with flying colours after two days with as much variety in warfare in them as even he could desire. No one regretted his departure, and no one ever wished for a return vi it. This adventure of Paul Jones impressed the people with the fact that our Lough was in a totally defenceless condition. Carrickfergus Castle even at its best days could not protect our shores.

A fort for the defence of Belfast has been built at Grey Point, the guns of which command the entrance to the Lough, and it is now almost completed.

The town of Belfast was seriously alarmed, and applied to the Government for assistance, but none was given, so the people took matters into their own hands and fitted out privateers with men and guns for protection. It was at this time that armed companies of citizens were formed, and they were the first of the famous Volunteers. Men of the highest rank enlisted, and rapid progress was made in preparation for any emergency.

The House of Lords wrote a letter of thanks to the Volunteers, who sought no reward and asked for no payment from the English Government. They took no military oath or obligation, but depended on their own resources, expecting to be engaged in war with France. During the winter they guarded the town and their intrepidity and knowledge protected both town and country from enemies. It would be a very curious sight now if the Volunteers were seen with their picturesque dress, of scarlet coat with black velvet facings, white waistcoats and breeches, going in procession to church on Sunday, and firing three volleys afterwards on the Parade as they returned. The Volunteers were at the beginning of their organisation a most useful and splendid body of men. There was a great Volunteer Convention held at Dungannon in the year 1782.

Annual reviews took place in Belfast, intense enthusiasm prevailed and all doors were open to receive them as honoured guests. The Charitable Society—now the old Poorhouse—gave shelter, and parades were held inside its walls. Reviews were held in the Plains and Falls Meadows for three days, in which thousands took part, with 100,000 spectators. Balls and assemblies were held every night, and Belfast was very brilliant, but dissensions came in, and the United Irishmen were formed. In 1793, the Government caused the Volunteer regiments to be broken up, but during the years of their existence the Volunteers had served the country, and served it well.