Irish Churches

Early Decorated Churches—Church of Killeshin—Examples at Rahan—Cormac's Chapel at Cashel

From A Hand-book of Irish Antiquities by William F. Wakeman

« Churches, etc. | Contents | Crosses, etc. »

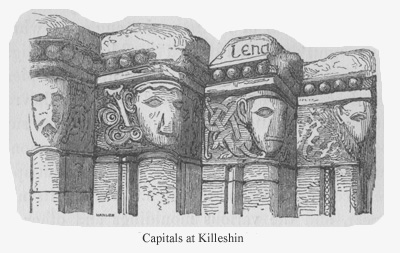

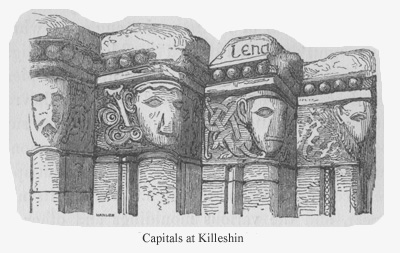

HE churches to which we have referred in the preceding pages are such as we have every reason to believe were generally constructed during the earlier ages of Christianity in this kingdom. How long the style continued is a matter of very great uncertainty. The horizontal lintel appears gradually to have given place to the semicircular arch-head. The high-pitched roof becomes flattened, the walls lose much of their Cyclopean character, and in several examples a considerable quantity of cement appears to have been used. The windows exhibit a slight recess, or a chamfer upon the exterior, and are of greater size; a small bead-moulding is occasionally found extending round an arch upon the interior. The walls are generally higher, and of somewhat inferior masonry. As the style advanced, the sides of the doorways became cut into a series of recesses, the angles of which were slightly rounded off. The addition of a slight moulding, at first a mere incision, upon the piers, would seem to have suggested pillars. Chevron and other decorations, which in England are supposed to indicate the Norman period, are commonly found, but they are generally simple lines cut upon the face and soffit of the arch. Pediments now appear, and the various mouldings and other details of doorways and other openings become rich and striking, and, in some respects, bear considerable analogy to true Norman work. The capitals frequently represent human heads, the hair of which is interlaced with snake-like animals. A similar style of decoration is displayed upon the doorways of several of the Round Towers, as at Timahoe. The church of Killeshin, in the Queen's County, lying at a distance of about two miles from Carlow, appears to have been one of the most beautiful structures of this class ever erected in Ireland. Its doorway, until very lately, retained in a remarkable degree the original sharpness of its sculpture. We were informed that, about fifteen years ago, a resident in the neighbourhood used to take pleasure in destroying, as far as lay in his power, the beautiful capitals here represented, and that to his labours, and not to the effects of time, we may attribute the almost total obliteration of an Irish inscription which formerly extended round the abacus, and of which but a few letters at present remain.

HE churches to which we have referred in the preceding pages are such as we have every reason to believe were generally constructed during the earlier ages of Christianity in this kingdom. How long the style continued is a matter of very great uncertainty. The horizontal lintel appears gradually to have given place to the semicircular arch-head. The high-pitched roof becomes flattened, the walls lose much of their Cyclopean character, and in several examples a considerable quantity of cement appears to have been used. The windows exhibit a slight recess, or a chamfer upon the exterior, and are of greater size; a small bead-moulding is occasionally found extending round an arch upon the interior. The walls are generally higher, and of somewhat inferior masonry. As the style advanced, the sides of the doorways became cut into a series of recesses, the angles of which were slightly rounded off. The addition of a slight moulding, at first a mere incision, upon the piers, would seem to have suggested pillars. Chevron and other decorations, which in England are supposed to indicate the Norman period, are commonly found, but they are generally simple lines cut upon the face and soffit of the arch. Pediments now appear, and the various mouldings and other details of doorways and other openings become rich and striking, and, in some respects, bear considerable analogy to true Norman work. The capitals frequently represent human heads, the hair of which is interlaced with snake-like animals. A similar style of decoration is displayed upon the doorways of several of the Round Towers, as at Timahoe. The church of Killeshin, in the Queen's County, lying at a distance of about two miles from Carlow, appears to have been one of the most beautiful structures of this class ever erected in Ireland. Its doorway, until very lately, retained in a remarkable degree the original sharpness of its sculpture. We were informed that, about fifteen years ago, a resident in the neighbourhood used to take pleasure in destroying, as far as lay in his power, the beautiful capitals here represented, and that to his labours, and not to the effects of time, we may attribute the almost total obliteration of an Irish inscription which formerly extended round the abacus, and of which but a few letters at present remain.

It appears that within the last half century there has been a greater destruction of Irish antiquities, through sheer wantonness, than the storms, and frost, and lightning, of ages could have accomplished.

Such acts of Vandalism have not been always perpetrated by the unlettered peasant. Indeed, the devotional feeling of the labouring classes of the greater part of Ireland leads them to regard antiquities, especially those of an ecclesiastical origin, with a feeling of veneration. These outrages have most frequently been committed by contractors for the erection of new buildings, for the sake of the stones, or, for the same reason, by men of station and education, who should have recollected that age and neglect cannot deprive structures once consecrated to God, and applied to the service of religion, of any portion of their sacred character. The church of Killeshin is, perhaps, late in the style. The arches [there are four concentric] which form the doorway display a great variety of ornamental detail, consisting of chevron work, animals, &c. &c. A pediment surmounts the external arch, and a window in the south side wall is canopied by a broad band, ascending and converging in straight lines. A window of similar construction appears in the Round Tower of Timahoe, already alluded to. The most remarkable specimen of this style of church remaining, occurs at Rahin, near Tullamore, in the King's County. It is most minutely described and illustrated by Dr. Petrie in pages 240, 241 of the work to which we have so frequently alluded; and, as it appears from historical evidence to belong to the eighth century, there is, perhaps, no structure in the British Isles of greater interest to the archaeologist. A triple choir arch, and a circular window, highly ornamented, are the only lemaining features of the original church. The piers of the former are rounded oft into semi-columns, with capitals of very singular character, totally distinct from Norman work. The bases are globular in form, and are sculptured in each compartment out of a single stone. The capitals or imposts are ornamented upon their angles with human heads, the hair of which is carried back, and represented by shallow lines cut upon the face of the stone in a very fanciful manner.

A pediment surmounts the external arch, and a window in the south side wall is canopied by a broad band, ascending and converging in straight lines. A window of similar construction appears in the Round Tower of Timahoe, already alluded to. The most remarkable specimen of this style of church remaining, occurs at Rahin, near Tullamore, in the King's County. It is most minutely described and illustrated by Dr. Petrie in pages 240, 241 of the work to which we have so frequently alluded; and, as it appears from historical evidence to belong to the eighth century, there is, perhaps, no structure in the British Isles of greater interest to the archaeologist. A triple choir arch, and a circular window, highly ornamented, are the only lemaining features of the original church. The piers of the former are rounded oft into semi-columns, with capitals of very singular character, totally distinct from Norman work. The bases are globular in form, and are sculptured in each compartment out of a single stone. The capitals or imposts are ornamented upon their angles with human heads, the hair of which is carried back, and represented by shallow lines cut upon the face of the stone in a very fanciful manner.

The window, which is seven feet six inches in diameter, is composed of stones unequal in size, and displaying chevron ornaments in very low relief.

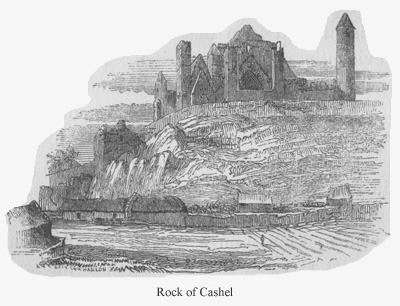

It is a fact well worthy of observation, that the details which we have mentioned as characteristic of this style are never found associated with others known to belong exclusively to the Norman period; and that in several structures, as in Cormac's Chapel at Cashel, an erection of the early part of the twelfth century, the usual Norman capitals, ornaments, &c. &c., appear. It is an interesting consideration, that, as the style of architecture usually denominated Norman was certainly practised in Ireland long previous to the English Invasion, there is a great probability that it was neither unknown nor unused in England before A.D 1066, and that, consequently, many churches in that country, usually supposed to be Norman, may, in fact, be true Saxon works.

The railway now in the course of formation will soon bring Cashel within a few hours' journey of the metropolis; and as the ruins upon the celebrated Rock are unparalleled, at least in Ireland, for picturesque beauty and antiquarian interest, there are few by whom a visit to the place would not be remembered with pleasure. Cormac's Chapel, which, with the exception of the Round Tower, is the most ancient structure of the group, was built by Cormac Mac Carthy, King of Munster, in the beginning of the twelfth century. It is roofed with stone, and in its capitals, arches, and other features and details, the Norman style is distinctly marked. The plan is a nave and chancel, with a square tower on each side, at their junction. The southern tower is ornamented externally with six projecting bands, three of which are continued along the side walls of the structure; and it is finished at the top by a plain parapet, the masonry of which is different from that of the other portions, and evidently of a later period. The northern tower remains in its original state, and is covered with a pyramidical cap of stone. An almost endless variety of Norman decorations appear upon the arches and other features of the building, both within and without. Both nave and chancel are roofed with a semicircular arch, resting upon square ribs, which spring from a series of massive semi-columns set at equal distances against the walls. The bases of these semi-columns are on a level with the capitals of the choir arch, the abacus of which is continued as a string course round the interior of the building. The walls of both nave and chancel beneath, the string course are ornamented with a row of semicircular arches, slightly recessed, and enriched with chevron, billet, and other ornaments and mouldings. Those of the nave spring from square imposts resting upon piers, while those in the chancel have pillars and well-formed capitals. There are small crofts, to which access is gained by a spiral stair in the southern tower, between the arches over both nave and chancel, and the external roof. These little apartments were probably used as dormitories by the ecclesiastics. A similar croft in the church of St. Doulough's, near Dublin, is furnished with a fire-place, a fact which clearly demonstrates that they were applied to the purpose of a habitation.

The doorways of Cormac's Chapel are three in number,—one in the centre of the west end, and one in each of the side walls of the nave, within a few feet of the west gable. The northern and southern doorways are original, and are headed with a tympanum or lintel between the aperture and the semicircular arches above. They are both exceedingly rich in sculpture, but the northern doorway appears to have been the chief entrance, as it is considerably larger, and more highly decorated, than the other. It is surmounted with a canopy, and the tympanum is sculptured with a very singular device, representing a combat between a centaur armed with bow and arrow, and a huge animal, probably intended for a lion. The head of the centaur is covered by a conical helmet with a nasel, and he is shooting a barbed arrow into the breast of the lion. A small animal beneath the feet of the latter appears to have been slain in the encounter.

The southern doorway, which is now filled up, is not canopied, and its tympanum is sculptured with a single animal, not unlike the lion upon the other.

At Cashel, the perfect round tower, Cormac's Chapel, the magnificent cathedral founded by Donogh O'Brien, King of Thomond, circa 1152, the ancient castle of the Archbishops, Hoar Abbey, situated upon the plain immediately beside the Rock, and the numerous crosses and other remains, afford most valuable studies for the architectural antiquary or the artist.