Raths or Duns in Ireland

Rath at Downpatrick—Subterranean Chambers—Hill of Tara—Rath Righ, or King's Rath—The Forradh—Teach Cormac—Pillar Stone at Tara—Mound of the Hostages—Rath Graine—Rath Caelchu—Fothath Rath Graine—The Banqueting Hall at Tara—The Lis, or Cathair—Staigue Fort—Dun Aenghuis

From A Hand-book of Irish Antiquities by William F. Wakeman

« Sepulchral Mounds | Contents | Stone Circles »

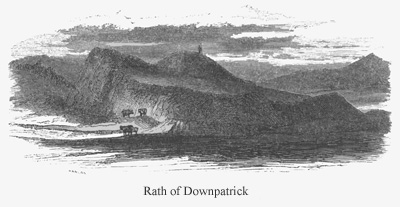

HE earthen duns, or raths, which are found in every part of Ireland, where stone is not abundant, often consist merely of a circular entrenchment, the area of which is slightly raised above the level of the adjoining land. But they most frequently present a steep mound, flat at the top, and strongly entrenched, the works usually enclosing a space of ground upon which, it is presumed, the houses of lesser importance anciently stood, the mound being occupied by the dwelling of the chief. The engraving represents the celebrated rath at Downpatrick, in the county of Down, formerly called Rath Keltair, and will afford an excellent idea of the general appearance of the more remarkable of these remains.

HE earthen duns, or raths, which are found in every part of Ireland, where stone is not abundant, often consist merely of a circular entrenchment, the area of which is slightly raised above the level of the adjoining land. But they most frequently present a steep mound, flat at the top, and strongly entrenched, the works usually enclosing a space of ground upon which, it is presumed, the houses of lesser importance anciently stood, the mound being occupied by the dwelling of the chief. The engraving represents the celebrated rath at Downpatrick, in the county of Down, formerly called Rath Keltair, and will afford an excellent idea of the general appearance of the more remarkable of these remains.

Of the number of raths which we have examined, we have not in one instance known the mound to contain a chamber; but when the work consists merely of the circular enclosure, of which mention has been already made, excavations of a bee-hive form, lined with uncemented stones, and connected by passages sufficiently large to admit a man, are not unfrequently found. These chambers were probably used as places of temporary retreat, or as store-houses for corn, &c. &c , the want of any ventilation, save that derived from the narrow external entrance, rendering them unfit for the continued habitation of man.

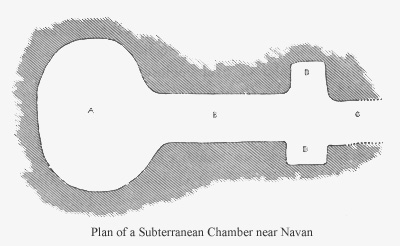

We are not aware that any rath in the neighbourhood of Dublin contains a chamber or chambers of this kind. They are common only in the southern and western parts of Ireland; but subterraneous works, similar to those usually found in the forts of Connaught and Munster, occur in Meath, and perhaps in other Leinster counties. An excavation which was a few years ago accidentally discovered upon the grounds of P. P. Metge, Esq., in the vicinity of Navan, maybe described as a good example.

The chamber A is of an oval form, and measures in length eleven, in height six, and in breadth nine feet; B is a passage or gallery (in length fifteen feet), which has fallen in at C; D D are niches let into the sides of the gallery, which, like the chamber, is lined with uncemented stones, laid pretty regularly.

The celebrated hill of Tara, in the county of Meath, from the earliest period of which we have even traditional history, down to the middle of the sixth century, appeals to have been a chief seat of the Irish kings. Shortly after the death of Dermot, the son of Fergus, in the year 563, the place was deserted, in consequence, as it is said, of a curse pronounced by Saint Ruadan, or Rodanus, of Lorha, against that king and his palace. After thirteen centuries of ruin, the chief monuments for which the hill was at any time remarkable, are distinctly to be traced. They consist, for the most part, of circular or oval enclosures, and mounds, called in Irish, Raths and Duns, within or upon which the principal habitations of the ancient city undoubtedly stood. The names by which we shall describe the various remains are given altogether upon the authority of the Ordnance Survey Map, upon which they were laid down by Dr. Petrie and J. O'Donovan, Esq , after a very careful study of several ancient Irish documents, in which were found most minute descriptions, occasionally accompanied by plans, of the various monuments as they existed previously to the twelfth century.

The rath called Rath Righ, or Cathair Crofinn, appears anciently to have been the most important work upon the hill, but it is now nearly levelled with the ground. This rath, which is of an oval form, measures in length, from north to south, about 850 feet, and appears in part to have been constructed of stone.

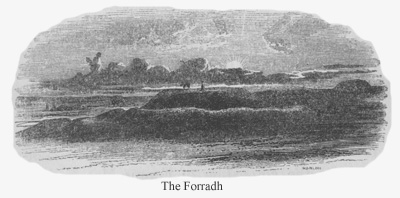

Within its enclosure are the ruins of the Forradh, a mound, of which the annexed engraving is an accurate representation, and of Teach Cormac, or the House of Cormac. The mound of the Forradh is of considerable height, flat at the top, and encircled by two lines of earth, having a ditch between them. In its centre is a very remarkable pillar stone, which formerly stood upon, or rather by the side of a small mound, lying within the enclosure of Rath Righ, and called Dumha-na-n-Giall, or the Mound of the Hostages, but which was removed to its present site to mark the grave of some men slain in an encounter with the King's troops during the rising of 1798.

It has been suggested by Dr. Petrie, that it is extremely probable that this monument is no other than the celebrated Lia Fail, or Stone of Destiny, upon which, for many ages, the monarchs of Ireland were crowned, and which is generally supposed to have been removed from Ireland to Scotland for the coronation of Fergus Mac Eark, a prince of the blood-royal of Ireland, there having been a prophecy that in whatever country this famous stone was preserved, a king of the Scotic race should reign. Certain it is, that in the MSS. to which Dr. Petrie refers (the oldest of which cannot be assigned to an earlier period than the tenth century), the stone is mentioned as still existing at Tara; and "it is an interesting fact, that a large obeliscal pillar-stone, in prostrate position, occupied, till a recent period, the very situation on the hill pointed out as the place of the Lia Fail by the Irish writers of the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth centuries."

upon which, for many ages, the monarchs of Ireland were crowned, and which is generally supposed to have been removed from Ireland to Scotland for the coronation of Fergus Mac Eark, a prince of the blood-royal of Ireland, there having been a prophecy that in whatever country this famous stone was preserved, a king of the Scotic race should reign. Certain it is, that in the MSS. to which Dr. Petrie refers (the oldest of which cannot be assigned to an earlier period than the tenth century), the stone is mentioned as still existing at Tara; and "it is an interesting fact, that a large obeliscal pillar-stone, in prostrate position, occupied, till a recent period, the very situation on the hill pointed out as the place of the Lia Fail by the Irish writers of the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth centuries."

Dr. Petrie, after remarking upon the want of agreement between the Irish and Scottish accounts of the history of the Lia Fail, and on the questionable character of the evidence upon which the story of its removal from Ireland rests, observes: "That it is in the highest degree improbable, that, to gratify the desire of a colony, the Irish would have voluntarily parted with a monument so venerable for its antiquity, and deemed essential to the legitimate succession of their own kings."

If the Irish authorities for the existence of the Lia Fail at Tara, so late as the tenth or eleventh century, may be relied upon, and their extreme accuracy in other respects is sufficiently clear, the stone carried away from Scotland by Edward the First, and now preserved in Westminster Abbey, under the coronation chair, has long attracted a degree of celebrity to which it was not entitled; while the veritable Lia Fail, the stone which, according to the early bardic accounts, roared beneath the ancient Irish monarchs at their inauguration, remained forgotten and disregarded among the green raths of deserted Tara.

The Teach Cormac, lying to the south-east of the Forradh, with which it is joined by a common parapet, may be described as a double enclosure, the rings of which upon the western side become connected. Its diameter is about 140 feet.

An inspection of these remains alone will give the student of Irish antiquities a very correct idea of the general character of the ordinary raths or duns, but as we shall suppose the reader to be upon the spot, we strongly recommend an examination of the three raths called Rath Graine, Rath Caelchu, and Fothath Ratha Graine, lying upon the slope of the hill, to the north-west of Rath Righ. Rath Graine is said to have belonged to, and to have been named after, Graine, a daughter of King Cormac Mac Art, and the wife of Finn Mac Cumhaill, the Fingal of Mac Pherson's Ossian.

The ruins of Teach Midhchuarta, or the Banqueting-hall of Tara, occupying a position a little to the north-east of Rath Righ, consist of two parallel lines of earth, running in a direction nearly north and south, and divided at intervals by openings which indicate the position of the ancient doorways. These doorways appear to have been twelve in number (six on each side); but as the end walls, which are now nearly level with the ground, may have been pierced in a similar manner, it is uncertain whether this far-famed Teach-Midhchuarta had anciently twelve or fourteen entrances. Its interior dimensions, 360 by forty feet, indicate that it was not constructed for the accommodation of a few, and that the songs of the old Irish bards, descriptive of the royal feasts of Teamor, may not be the fictions that many people are very ready to suppose them. If, upon viewing the remains of this ancient seat of royalty, we feel disappointed, and even question the tales of its former magnificence, let us consider, that since the latest period during which the kings and chiefs of Ireland were wont here to assemble, thirteen centuries have elapsed, and our surprise will not be that so few indications of ancient grandeur are to be found, but that any vestige remains to point out its site.

THE LIS, OR CATHAIR

In order to afford the reader a clear insight into the character of Irish antiquities generally, it will be necessary to describe a class of ruins now remaining only in the more remote districts of Connaught and Munster. We allude to the stone Cathair, or, as it is sometimes styled, Lis, or Dun, which is found so commonly along the western and southwestern coasts of Ireland, and upon the adjoining islands.

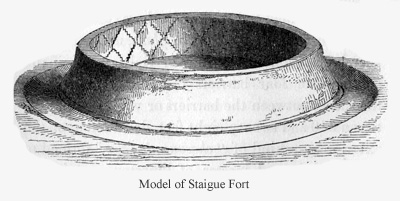

They probably owe their preservation to the abundance of stone in the districts where they are generally found, the neighbouring inhabitants thus having no inducement to destroy them for the sake of their materials. The subjoined engraving represents a model which may be seen in the museum of the Royal Dublin Society House, of the cathair at Staigue, in the county of Kerry, probably the most perfect example of its class to be met with in any part of the south of Ireland. It consists of a circular wall of uncemented stones, about eighteen feet in height, and twelve in thickness, enclosing an area of eighty-eight yards in diameter. Upon the internal face of the wall are regular flights of steps—the plan of which will be best understood by a reference to the wood-cut—leading to the highest part of the building. The doorway is composed of large unhewn stones, and is covered by a horizontal lintel. A ditch, now nearly filled up, anciently defended the wall upon the exterior.

The fortress called Dun Aenghuis, upon the great island of Aran, in the bay of Galway, originally consisted of four barriers of uncemented stones, the spaces between the barriers or walls varying between 640 and twenty-eight feet, defended upon the exterior by a kind of "chevaux-de-frise" formed of large and jagged masses of limestone, set in the clefts of the rock upon which the fort stands. The inner barrier, which in some parts is ten feet in thickness, and twelve in height, and which in its thickness contains a chamber capable of containing but two or three persons, is composed of three distinct walls of irregular masonry, lying close together, and apparently forming one mass. Upon the internal face of this triple wall are ranges of steps similar to those in Staigue fort. The external division rises several feet higher than the other portion, and forms a kind of breast-work, well adapted to cover the defenders of the fort from the missiles of assailants.

Several cathairs which we have examined are not circular in plan, but appear to have been formed to suit the contour of the eminence upon which they stand; and others are of an oval form. Small, circular, stone-roofed buildings, called Clochans, are commonly found within their enclosure; and similar structures, unconnected with any other work, are numerous in the counties of Galway and Kerry. Upon High Island, off the coast of Connemara, Inis Glory, off the coast of Erris, and upon other islands adjoining the western and south-western coasts of Ireland, are houses built upon precisely the same plan, which were evidently erected in connexion with ancient monastic establishments.