The Five Counties

CROMWELL was not content with enclosing the Irish; he determined that the whole seaboard on the Channel should be especially garrisoned. It so happened that Antrim and Down were held by the Presbyterian settlers, and that the English Pale had long been subjected; but the counties below Dublin required attention. In the old days, the watchmen aloft on Dublin Castle had seen a hostile country whenever their eyes were turned to the South, for the grey hills of Wicklow had always been retained by the Irish. That was the country of the warlike O'Tooles. This state of affairs had been in part remedied before he arrived, since the O'Tooles had been broken at last, and he had done something towards ending it when, after his triumph at Drogheda, he had marched ravaging from Dublin to Wexford. Still, he considered that there was room for improvement; so in July 1654 he enacted that all Papists, rich or poor, should disappear from the counties of Wicklow and Wexford and Carlow and Kildare, and from the parts of Dublin below the Liffey, and that any who disobeyed should be court-martialled and executed as spies. This part, which was thus to become thoroughly Protestant, was bounded by the Liffey and the Barrow and called the Five Counties.

Two of these counties, Carlow and Kildare, were inland; but they adjoined the others and were fertile, as indeed the whole district was, for even in Wicklow there were rich valleys among the hills. In this part no one was to be allowed to employ a Catholic in any capacity or to tolerate the sight of one. This resolute scheme failed in part. The new landlords found it impossible to secure enough Protestant menials and labourers; and many of those that were imported from England fell into Irish ways. The result was that while nearly all the mansions belonged to Protestants, most of the thatched roofs sheltered Catholics. And another result was that these peasants, like those of the Irish Pale, had for some time a vivid remembrance of wrongs. So by attempting to make the Five Counties a Protestant stronghold, he inspired the ferocity of the rising of Ninety-Eight.

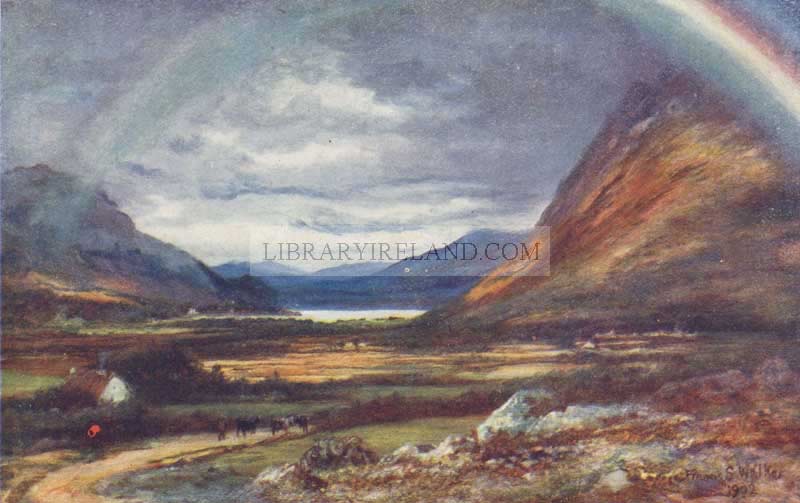

THE PASS OF KYLEMORE

HERE is one of the finest combinations of mountain and lake scenery in Ireland; the hills, ranging from the richest brown to the deepest blue, are best seen after a storm.

If the men of Connemara had risen, making a last desperate stand in the mountains in which they had been driven to bay, it would have appeared natural enough; but when you see Wexford's soft meadows and gradual moors and wide level roads under branches, and note the methodical and respectable lives of its people, it is hard to believe that this was the scene of Ireland's most frantic rebellion. There can be little doubt that if the peasants of Wexford had found a general worthy of the name in that year, 1798, and had been backed by their countrymen, they would have succeeded; but they had captains who knew nothing of war, and they were left to fight their battle alone. How was it that they succeeded at all, as they did for a time? It was, I think, mainly because they were among the least Irish of Irishmen.

It would not be safe to say this to a Wexford man, and indeed what other county has paid so great a price for the wearing of the Green? Yet the fact remains that this one had been continually stocked from abroad. The Danes peopled it when they built Wexford (Weissfiord they called it) at the mouth of the Slaney; the Normans first landed on its southern shore on the Beaches of Bannow and copied the Danes; Strongbow colonised it from Wales, and to this day the folk of the Baronies of Bargy and Forth have much more in common with their Welsh kinsmen than with their neighbours of Ireland. Then more English settlers came, and then the Cromwellian flood, and afterwards Dutchmen. And through all this time, and probably from pre-historic days, there was a steady communion with Cornwall and Wales. Just as Antrim was always in touch with Scotland, so was Wexford with the opposite Celts on the other side of the Channel. From all this it came to pass that the men of Wexford had in their nature a foreign element. Because they were law-abiding and dogged, they were more dangerous when they were frenzied; because they had always lived in union, they struck together; and they rose, instead of talking about it and postponing it, because they were silent and not given to dreams.

In those days, there must have been in this county a look of Dutch primness. There were a great many windmills on the wide moors, and plenty of solid farms in the meadows. But in that terrible year most of those farms were wrecked, and now few of the windmills signal to one another—you see many gaunt deserted towers in their places. One such tower, or rather the butt of one, stands on a green shoulder of the moors above ripe pleasant fields. From its narrow door you look down on quiet Enniscorthy, a cluster of old houses beside a weedy and shaded little river. The green side beneath the ruin is called Vinegar Hill. In that roofless butt the rebels imprisoned their victims; on that long slope they encamped, or huddled rather, with the sky as their roof, and made their last stand when all hope was gone.

Several years ago, I wandered alone over this county, seeking traditions of that rising. I found a very few old people who had been out as children, and many whose fathers and mothers had tramped in that army of fugitives. The rebels comprised men, women, and children of all ages; for when once that death-struggle had begun, the most peaceful and the most timid alike fled to the camps out of fear of the Yeomen. These Yeomen were Irish, and so were the Militia and the Fencibles, and nearly all the troops fighting for England, except the Hessian mercenaries. All these wreaked vengeance with a Puritan rage. It was a national affair; and each side showed Irish courage and Irish cruelty. It was an internecine Religious War: to the rebels as to their children it was "the turn-out agin the Orangemen." Each side was desperate, and not without reason.

As for the traditions I sought, it was soon evident that I was too late in the field. Much had been forgotten and more had been distorted by repetition; yet there were some illuminating stories. For instance, there was one of a rebel captain, who sat in judgment on a former neighbour of his, an Orangeman, on Vinegar Hill. "Wasn't I a good neighbour to you, ay, and a loving friend for fifteen long years?" cried the Orangeman. "You were, dear, you were," said his judge. "Didn't I succour you when you were down with a heavy load of the fever?" "You did, dear, you did," said his judge, "and you are the fitter to die." "What will we do with him, captain?" asked one of the guards; and the answer was "Pike him, Agra." This was the spirit of that war, the old hatred and mutual fear blotting out all other thoughts.

How was it that Wexford struggled and fell alone? This was in part caused by its habitual independence. The word had gone round to every village in Ireland; but at the last moment the day of the general rising had been postponed. It may be that the leaders had not counted much on these quiet men, and so did not trouble to warn them of the change; or perhaps Wexford knew of it and would not take heed. Because its people were slow to make up their minds, they were the less likely to alter them. Besides, you must remember the dislocation of Ireland. Each county was aloof, as the Swiss Cantons are now and as the English Shires were once; and they could only have been united by following some common leader. The men who became Wexford's leaders were quite unknown out of it. For which reasons it came to pass that while the battle of New Ross was raging on one shore of the Barrow, the peasants of Kilkenny were seen digging and ploughing on the other.

New Ross had been in its time typical of Wexford; for its first fortifications were built to exclude its "naughtie and prowlying neighbours" (as Holinshed wrote), of whom the naughtiest just then was a Geraldine. This battle, its last, was typical too, not only of the ways of the county but also of those of all Ireland; for when it was begun by a mistake a great many of the rebels abandoned hope and their comrades. In the same way the other counties of Ireland, despairing before there was any need to despair, left the men of Antrim and Wexford without help. It is worth noting that the only struggles in Ninety-Eight were in Protestant Antrim and in Cromwell's Five Counties.

Of these five the most frequented is Wicklow. This is due to its position near Dublin and to the fact that its charms have been made familiar by songs. It is not to be compared with the Highlands of the battered and mournful West; those are of sterner stuff. Here the hills are more pleasant and the smooth valleys find a quieter sea. Yet over it broods the sorrow of Ireland. Cromwell's work was done thoroughly: there is hardly a ruin to tell of the centuries of Irish defiance. Instead of ivied castles you see Georgian houses, all built to command delectable views. These suggest the enviable lives of retired tradesmen or of families who, drawing their rents from less fortunate places, chose to live here within the light of the Viceroy's Court. You may chance to remember other things, strange and true tales of the old chiefs, or incidents of the exterminating war, such as Coote's words when he slaughtered the children—("nits will be lice," said he, "nits will be lice")—and by that justification he expressed the spirit of all who hunted the Irish Wolves. But of such matters there is no trace, for Sidney and Coote and Cromwell eradicated even the ruins when at length they established in Wicklow the peace of the Pale.

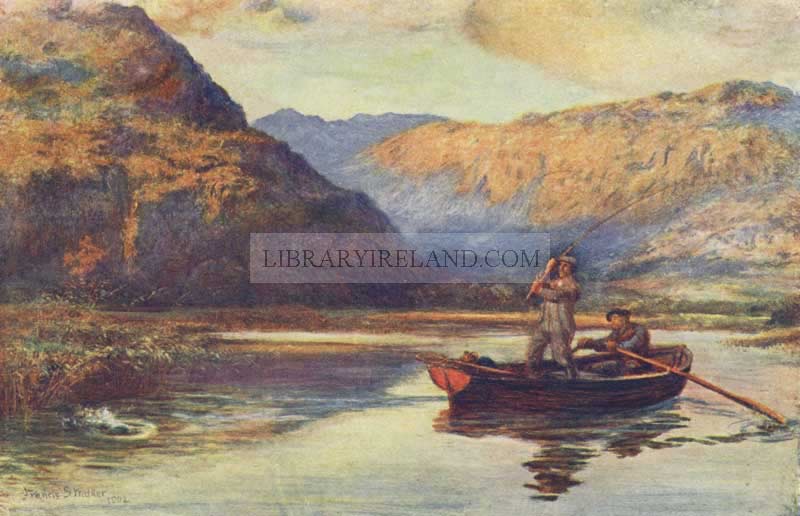

NEAR RECESS, CONNEMARA

AFTER leaving Galway westward, we get the first impression of Connemara on approaching Recess; here the Twelve Pins, or Bens, standing clear and bare, without a vestige of foliage, dominate the landscape in all directions. They arise from what is practically a great plain through which run rapid streams, while close under the hills are several loughs that suggest a fisherman's paradise.

In this sepulchral peace there is the suggestion of sanctity that was recognised when burial-grounds were called God's Acres. Wherever you go in Ireland you tread consecrated ground. Here among these mellow hills and serene valleys you find the restored domination of the primitive monks. It was restored by the English when they made Wicklow a solitude again. The castles of the chiefs were obliterated; but the rude huts and chapels that were so ancient in their time have survived. Visit Glendalough, that dim hidden lake, of which it is told that some spell forbade any bird to sing above it, and you will find it so mysteriously lulled and so separate that you could imagine it never profaned. It seems dedicated still to the men who in this refuge forgot transitory cares.